Lydia Wilkins is a freelance journalist and author based in the UK who covers disability and social issues. Her work has appeared in publications such as The Metro, The Independent, Refinery 29, The Daily Mail and PosAbility Magazine. She writes a newsletter on Substack discussing the intersection between feminism and disability culture. Her debut book, “The Autism-Friendly Cookbook,” was published in November 2022. She is also an ambassador for AccessAble, an organization providing access guides across the UK.

During this episode, you will hear Lydia talk about:

- Her experience working as an autistic journalist

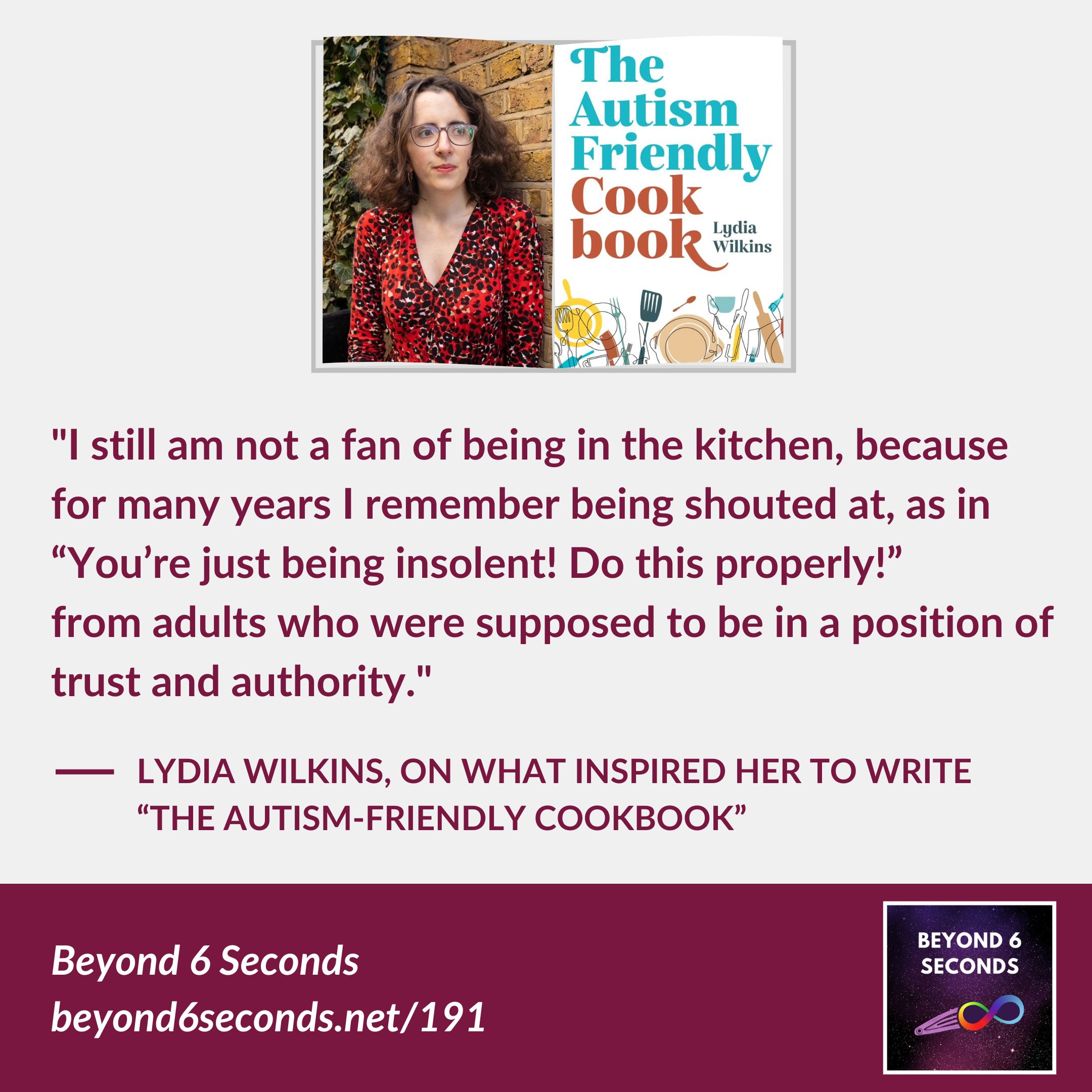

- What inspired her to write “The Autism-Friendly Cookbook,” and how her book makes cooking more accessible for autistic people

- How clear communication skills are both critical and underrated

- The difference between asking informed questions and expecting emotional labor from people with disabilities

Beyond 6 Seconds is also giving away a copy of “The Autism-Friendly Cookbook” to two of our listeners in the United States! Check out our pinned Twitter post at @Beyond6S on Monday, July 24th, 2023 for more information. Up to two winners will be chosen at random. Valid for US addresses only. Giveaway ends at 11:59pm EDT on Friday, August 4, 2023.

“The Autism-Friendly Cookbook” is also available for purchase on the Jessica Kingsley Publishers website, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Bookshop.org, and Waterstones.

Find out more about Lydia and her work at LydiaWilkins.co.uk, subscribe to her Substack newsletter The Disabled Feminist, and follow her on Instagram and Twitter.

Follow the Beyond 6 Seconds podcast in your favorite podcast player!

Support this podcast at BuyMeACoffee.com/beyond6seconds and get a shout-out on a future episode!

Subscribe to the FREE Beyond 6 Seconds newsletter for early access to my latest podcast episodes!

*Disclaimer: The views, guidance, opinions, and thoughts expressed in Beyond 6 Seconds episodes are solely mine and/or those of my guests, and do not necessarily represent those of my employer or other organizations.*

The episode transcript is below.

Carolyn Kiel: Welcome to Beyond 6 Seconds, the podcast that goes beyond the six second first impression to share the extraordinary stories of neurodivergent people. I’m your host, Carolyn Kiel.

Thanks for joining me for this episode of Beyond 6 Seconds. Today my guest is Lydia Wilkins, a freelance journalist and author of The Autism Friendly Cookbook. I’m gonna talk with Lydia about how her book helps make cooking more accessible to autistic people like herself, and the wide variety of recipes her book includes, as well as how her own life experiences as an autistic woman inspired her to write this book. We have a very lively discussion that contains some occasional swearing, just to let you know in case you’re listening in public or in front of the kids.

Also for a limited time, I’m partnering with Jessica Kingsley Publishers to give away a copy of The Autism Friendly Cookbook to two of my listeners in the U.S. I’ll tell you all about how you can enter the giveaway at the end of this episode.

Here’s some more information about Lydia for our conversation today. Lydia is a freelance journalist and author based in the UK who covers disability and social issues. Her work has appeared in publications such as The Metro, The Independent, Refinery 29, The Daily Mail and PosAbility Magazine. She writes a newsletter on Substack discussing the intersection between feminism and disability culture. And her debut book, the Autism Friendly Cookbook, was published in November 2022. She’s also an ambassador for AccessAble, an organization providing access guides across the U.K. Lydia, welcome to the podcast.

Lydia Wilkins: Hi. Thank you for having me.

Carolyn Kiel: Really excited to talk with you today. I guess to start off, how did you first realize that you are autistic?

Lydia Wilkins: I feel slightly a bit of an imposter when people ask me this question because I don’t have the standard kind of like light bulb moment, I guess you would call it. There was kind of, I guess you would say an accumulation of events in the sense that when I was in education, it was always that thing of: we think she’s struggling, but we don’t know how exactly.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: I remember that for a long time there was a lot of testing, for example, so to test if I had dyslexia and all sorts of other conditions. So the neurodiversities, as we now call it. When I got to secondary school, I think this is actually quite common. Um, so secondary school is kind of like high school in the US. With the kind of the step up, the transition, it sort of became kinda more obvious in the sense of socially struggling and particularly kind of things in classrooms and that sort of thing. So it kind of, sort of all accumulated, and I was eventually diagnosed in January 2015.

So the assessment happened, but there was a long period of time. The assessment services in the UK are chronically underfunded as they are pretty much everywhere.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: There was, I wanna say maybe six, seven months, possibly even a year between the assessment and being given kind of like the final send off. I was told two months shy of my 16th birthday. I’m now 24. And it was sort of one of those, I didn’t really sort of realize in the sense of sort of what that meant until after I was done with education.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: There wasn’t kind of like a light bulb moment, so I always felt like an imposter. I was never really told in the sense of kind of what this means, what I should expect and all that sort of thing. It’s even things like. I was never really told, for example, in terms of kind of when it comes to healthcare, how the kind of the ASD can interplay sort of with all kinds of things such as when it comes to digestive issues and even things like pain relief.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: I only found out a year prior to the pandemic about how sometimes we perceive pain differently sometimes.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: Nobody told me any of that. And it was always that thing where kind of like if I had gone to the dentist and like, you know, had the kind of like pain relief and all that, it would take ages and I was never quite sure why.

I eventually was given some support a year prior to the pandemic. The pandemic put a stop to that and here we are.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, it’s, everyone’s story is a little different. And some people I’ve talked to have that kind of light bulb moment. And then other people, like even for me in my own discovery, there was no like one critical moment that were like, Aha! It all makes sense now, or like this is definitely it. It’s just sort of gradual experiences and then looking back on your life.

Lydia Wilkins: Exactly. It’s more like the Hollywood montage rather than kind of like the moment in the movie where it’s like, aha, we’ve got them.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. Yeah, exactly. And even as an adult or a teenager getting the diagnosis, as you were saying, there really isn’t always like a clear path forward or that understanding of like, okay, what does this really mean for me? What kind of accommodations might I need in my life? What things should I keep in mind?

Lydia Wilkins: Oh, no one ever told me any of that.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: Nobody ever told me anything about that. I sort of had to go looking. It was things such as when I was at college, for example, they would give me extra time in exams only if there was kind of like a screaming standup row, to be totally honest.

Carolyn Kiel: Wow.

Lydia Wilkins: I think it sort of, that sort of started to change when I was a journalism trainee.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: So I was outside of the education system. I was covering a disability specific story, and I met a woman who had limb difference. She lives not that far from where I live, and it was really interesting to me, and it’s still sort of interesting retrospectively in the sense of sort of very often people do not realize that I have ASD.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: They do not realize I’m autistic. Um, it’s always the non-disabled individuals who are like really shocked by this.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: I remember going into her house and she sort of, I don’t know how she realized. I never said anything and she sort of unmasked me. And she gave me kind of, if I say sort of disability 101 in the space of maybe an hour and a half at her house outside of an interview we were conducting. She was always very direct in a brilliant way, and she was saying things like, you are far too self-deprecating. You need to be more direct, which is, I’m very aware that I can be self-directing very often, I’m not direct at all in the sense of communication is an issue, but she made the point to say, this will help you and it will mean that your access needs are actually taken a bit more seriously.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm.

Lydia Wilkins: In the UK we have The Equality Act, and nobody once took me aside and said, actually, according to the law, you have a disability and every organization has to give you accommodations.

It took me nearly six years after I was diagnosed to be told this, I think. It would’ve saved a lot of time and a lot of heartache if to have been told this, but it basically meant that virtually every organization that was supposed to give support basically said goodbye, like clear away.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: It’s so wonderful, isn’t it? It was sort of, we are supposed to help you, but we won’t.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. It’s funny that the law, at least in the United States, the ADA, that law is in place, so it’s like, oh, okay. Yes. Then if I’m at a workplace, then I am legally entitled to get accommodations. I. But there’s still that gray area because it’s reasonable accommodations. So who determines what is reasonable?

Lydia Wilkins: It’s also in terms of the reasonable, because even in the US, I’ve seen this play out in terms of what is and what is not reasonable.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: But there’s no kind of, I’m not sure what the phrase is. For me to enact reasonable adjustments, I would have to go away and sue. In the UK we do not do that very often.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: I don’t have the luxury of time, money, or the resource.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: There is no mechanism for enforcing your legal rights in this. Those are the tiny flaws that are cumbersome.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, it’s the same in the US. Even though we think we tend to sue more often than in other countries, but still, it’s an expenditure of time and money and often the person who would have to sue does not have those in abundance.

Lydia Wilkins: And also it takes time. If I was to go around correcting every inaccessible type thing, that would take forever.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: Like, come on, let’s have some perspective about this. I can’t just be like lawyers! every six seconds.

Carolyn Kiel: Right? Yeah. Cuz it’s every day you probably encounter something.

Lydia Wilkins: Exactly. This was a massive tangent. I’m so sorry.

Carolyn Kiel: No, I mean it’s part of the experience and you know, you mentioned that you became a journalist when you entered the working world. So like how did you decide that you wanted to be a journalist and what is that like being an autistic journalist?

Lydia Wilkins: When I was in education, the phone hacking scandal broke. So this was around a decade ago where Rupert Murdoch’s media empire was under attack.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: I remember when, for example, the day came when the Guardian in the UK published a story about how Milly Dowler, who had been murdered, had had her phone hacked. And I remember just sort of, there was this feeling of kind of like the world just seemed to stop turning and everyone was talking about this. When I was a teenager, the trial of the newspaper executives was happening in London. And I, I usually joke with people, this is basically how my mother got me diagnosed. Instead of going to recess, instead of doing that in, instead of being social and talking to people who were my classmates at the time, I would go into the school library and I would read every possible piece of news about the coverage of the trial. Like obsessively. I, I forget how long this was, this trial. But I, I remember reading it for months, like The BBC, Guardian, Daily Mail, Metro, like the whole thing.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: I remember kind of thinking, this is an amazing story and the fact that there is basically one single reporter who got this off the back of asking questions was sort of a revelation.

So this is really ironic because I’ve actually met the journalist who broke that story on a number of occasions. Just over a week ago, we were talking on the phone about something not connected to this. I had been to a summit with other journalists where we got to see people like Woodward and Bernstein on stage in UK. It was organized by Tina Brown. Um, he was talking to me about how it had been an amazing experience, this summit, because he had gotten to shake hands with his heroes, who were Woodward and Bernstein. There was this sense of just absolute wonder in his voice. This person turned 70 earlier this year, and it just sort of, I didn’t say at the time, but I just sort of wanted to say, do you not realize how ironic this is? Do you not realize how I view you? Like you’re talking to me about your heroes and like the sort of hero worship type thing.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: This is so ironic. And you don’t realize that was an influence to me very quite significantly. And we sometimes forget very often that we are incredibly privileged to tell the stories of other people. I like the kind of the license that it gives. So I was always told that I was overly curious.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: I was asking too many questions and sort of like being really awkward when I was in education, just because I wanted to learn a bit more than was the kind of set standard almost.

To have a notebook in your hand is a license to ask questions. That is the one thing that I really like doing. It allows me to have that kind of thing that I was never allowed as a child, I think.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: I realized I quite liked writing, but I realized pretty early on, I think I was about six or seven, I can’t really write fiction. So it was one of those things of like, oh, what can you write? You can sort of write the facts down, oh, that is what journalists do. But that’s partly to do with my theory of mind because my diagnostic profile is not particularly brilliant. So it’s one of those things, like the stories that were written down, if they were fiction, were just dreadful! But in the sense of if you start to write the facts, if you are profiling someone, that is significantly easier. And I think that’s actually something I quite enjoy doing, to be honest.

Carolyn Kiel: I mean, it sounds like being a journalist, one of the requirements is to be curious and ask good and tough questions, and that it sounds like that was something that maybe came somewhat naturally to you that you got to do.

Lydia Wilkins: I think I was, frankly, a pain in the ass to my instructors when I was child, to be honest. I won’t say who spoke to me about this. But there was an industry professional that I really admire. We had sort of interacted over the lockdown. I attended a webinar that they were conducting with the university, and we had emailed sort of backwards and forwards. We’d never met before. They had sent me one of the nicest emails I’d ever received.

Carolyn Kiel: Oh, nice. What was it about?

Lydia Wilkins: I had this run-in with a senior journalist at a big media organization, and they basically told me that I was never gonna be any good, effectively because of my disability.

Carolyn Kiel: Whoa.

Lydia Wilkins: That I would never be any good. Um, that I should go back to university. I never went, can’t go back to something you never went to. That apparently I was terrible. I was too young and all the rest of it. It was just extraordinary. And it was frankly the product of bullying, I would argue. If you are wanting to be a leader, that is not leadership. That’s just awful. And I was in tears over this.

But the industry professional, he emailed me to say, effectively, there are a lot of autistic journalists in this particular profession, my dear. You would be surprised by the amount that there are. It is an asset and it is an asset to be curious and to ask questions. That really meant a lot. I’ve only ever met one other person who’s like me.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: Um, it, it was just sort of mind blowing and I don’t know if it’s sort of overly pathologizing in a way, but he was saying how that there were more than I would expect. Yeah, I was sort of like, who do I know? Like trying to work out who were you referring to? Because this is extraordinary, this revelation. But it was one of the things where it was effectively, it was phrased in a way to effectively say, don’t stop doing what you’re doing.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: That really meant a lot. And I think, whenever students approach me sometimes, and people who are kind of, they want to go into the profession, that’s always the sort of thing that I try and pass onto them to say, the people who are the awkward ones, the kind of people who think out of the box, they are the sort of thinkers I think we need, really. It’s not a crime. We need more of that, I think.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. It doesn’t surprise me actually to hear that there are a lot of autistic journalists. Like probably a lot of journalists who are my age, like I’m in my mid forties, so anyone around there, you could very likely be autistic and just like never know it because the diagnosis was just so different back then and so many people just never got a diagnosis.

I’ve had the honor of interviewing, um, some autistic journalists on my show and yeah, they love that part of the job, asking questions and focusing on topics that don’t always get a lot of attention otherwise. So yeah. That’s really great.

So, just to clarify, the person who said that, like really bullying comment, and then the person who told you that there are more autistic journalists than you realize, that wasn’t the same person.

Lydia Wilkins: They were two different people. It just happened the same day, which was really weird.

Carolyn Kiel: Oh, wow.

Lydia Wilkins: That being said, I can’t say that this is particularly an accommodating industry.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, I mean, it’s gotta be challenging, the types of conditions you have to work on. I imagine that there’s a lot of stress that you have to really think very quickly on your feet, which is not something that is a particular skill of mind. But, I really admire people who can do that, just be able to come up with good questions quickly. Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: I’ll say when it’s interviews, so part of my ASD is the fact that I script, so yeah. I actually find talking sometimes to be actually quite difficult.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: It’s become more of an issue. So as a long covid patient, one of the things that I still struggle with, it feels like there’s a black hole in the middle of my brain, and sort of like words were lost when in quarantine. I’ve had to kind of relearn that.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: Sometimes when I talk, for example, words get muddled very easily and people don’t, they don’t seem to take very nicely to this. For example, if I’ve been in public, I’ve been asked if I’ve been intoxicated.

Carolyn Kiel: Oh!

Lydia Wilkins: Like it’s sort of like, it’s one o’clock, like it’s lunchtime. Like really? Do you think I’m really drinking at this time? It’s a bit sort of a, you’re seriously suggesting that I’m drinking heavily at lunchtime as if I have a problem. One that’s offensive, and two absolutely not. But in the sense of sort of, this is just explaining, when it comes to interviews, I virtually always have kind of the baseline, I guess you’d call it, kinda like the skeleton written out in my notebook.

Carolyn Kiel: Yep.

Lydia Wilkins: Just as a kind of prompt. So if there’s ever that moment of, oh my God, I cannot retrieve these words.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: That my saving grace, um, I will never be parted from my notebook. It’s a disability aid. What can I say?

Carolyn Kiel: I script out questions before my interviews and while I don’t necessarily ask them exactly, it really helps to have, as you said, that at least a skeleton or an outline or something in case I get to a point where it’s like, wait, I totally wanted to cover this topic and I completely forgot about it, or, you know, I don’t know what to ask next.

Lydia Wilkins: I even do it for phone calls, and people who are not autistic and people who do not have a disability find it really weird that I do this. But it’s one so that I can actually talk to you on the phone.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: I really hate doing it. Two, it’s also so that I partly have a record because again, sort of covid has frankly buggered my memory.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: Like the order of events. If there was too much going on, I cannot sort of sort the information. But it’s always that thing of, people find it really funny when they read the script afterwards. There is a crime journalist who is frankly, really intimidating.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: I really hope he listens to this one day, so I can say that and can sort of get my own back on this one, his nickname was the Teddy Bear.

Carolyn Kiel: Oh.

Lydia Wilkins: Because there was always sort of, he had kind of like two different modes where he would be sort of grizzly as in like the grizzly bear.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: Or the teddy bear, sort of like, really cuddly. And he is really difficult to talk to on the phone. He is really abrupt and frankly really quite rude, I think.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: It’s not necessarily personal, but it’s always that thing of when I don’t have the skill to deal with that.

And I found recently, I had a note from when we first interacted nearly two and a half years ago now. I found the scripting note. And it had the kind of like um, you know when you start off in a conversation where you’re like, hi, I’m calling for so-and-so, my name is. It had that, and then underneath this it had the phrase: compliment here. Say something nice about his work.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm. Stage directions!

Lydia Wilkins: Massive capital letters over the page! Which I find really sort of funny in the sense that sort of this person is very open about the fact that they have a massive ego. They’ve described themselves as having a massive ego to me previously. So in the sense of sort of people think that’s really quite weird. It just enables me just to talk to you freely rather than sort of panic and go, oh, I don’t know what I’m doing. Like I’m gonna be really weird.

Carolyn Kiel: No, I, I feel like there are some people who just naturally have that, the ability to just do it in their heads. Like, okay, this is, you know, but they’re doing the same thing. They just don’t write it down or think about it beforehand.

Lydia Wilkins: Yeah.

Carolyn Kiel: Okay. So your background is in journalism, but you’ve recently written a book that’s a cookbook, so I’m, I’m so interested to see, how did you get the idea or the inspiration to write the Autism Friendly Cookbook?

Lydia Wilkins: Honestly, it was because I was pissed off. It was never supposed to happen! In the first lockdown, I was made aware that I was eligible for a benefit from the state because as we talked about previously, autism is considered a disability.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: And therefore I am eligible for monetary support. That particular benefit is known for being utterly dreadful. It’s things like where cancer patients have been asked like, have you stopped being ill yet? Or it’s things like if you have someone who is a veteran who is an amputee because they had gone off to Iraq or whatever, questions would be asked, like, so why didn’t you kill yourself? Or questions like that. It’s dreadful.

It was one of these things where I knew it was gonna be bad. I didn’t know how bad this would be, and I had to sit through different assessments and all the rest of it. It’s also the thing that because I don’t look disabled, quote unquote.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: Very often people don’t get it. So I sat through different assessments and things. It was sort of laughable on kind of round one because what I was saying had been totally twisted.

So it was apparently, instead of being an autistic person who still lived at home, apparently I was a senior journalist who would fly all around the world, and all I needed was a bit of help with communication like that is, I’m not being funny, but with all due respect, that’s not autism at all. You don’t just need a bit of help.

It was, yeah, it basically said, oh, she’s just a bit shy. I’m not shy, I’m just incapable.

Um, there was this line in the particular assessment where it also said that I could just learn how to cook. If I could just learn, do you think I could maybe like, you know, learn not to be autistic? Like, It was sort of beyond stupidness.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. Like “if you just set your mind to it, you could do it.”

Lydia Wilkins: It’s sort of funny to me, in a kind of bitter way, the amount of people who think that they have been really helpful, but they go, “you can just learn how to do this.” I can’t just learn because then I could just stop being autistic. Neurologically, I will forever be this way until the day I die. I’m sorry if it inconveniences you. But I would be a pain in your ass, otherwise. Like, come on now. Let’s just, let’s just be upfront about this.

It’s one of these things where if you are working on a project or a story, it comes to you sometimes in really quite weird ways. I remember there was a period of about four days where I was getting really quite cross about this one particular line. I had always been discriminated against when in education, for example, when it came to being taught how to cook, I would argue that the teachers were also bullies. They were awful. I remember waking up as a child from about the age of 11, really hating it. Like I, it was the whole anxiety borne in the stomach. I remember asking my mother, can I miss these classes? They enabled the other pupils in the class to be awful to me. Despite the fact at the time I was still on the kind of waiting list to be diagnosed.

It’s one of those things where I was talking to multiple people, autistic, otherwise, and over the course of about four days. It was one of these things where, a kind of sort of universal shape was being drawn out of this, how all of the kind of people that I assembled basically had the same issues that I did. And it was sort of like, oh my God. Like why did nobody ever say anything? Why did nobody ever adapt? I still relatively am not a fan of being in the kitchen because for many years it was kind of like, I remember being shouted at as in, “oh, you are just being insolent, like do this properly!” From adults who were supposed to be in a position of trust or authority. That doesn’t help.

So over the course of four days, again, going back to the trusty notebook, I was scribbling madly. Uh, so it was things like I would wake up in the middle of the night, sort of 2:00 AM 3:00 AM 4:00 AM to write stuff down.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: That became a pitch to the publisher as a cookbook idea. Because it was one of those things where sort of like, fuck this, frankly, I’m sorry to say that, but um, It was one of those things where I wanted to just prove the point, really, in the sense of these assessments are utterly degrading. It was one of the most humiliating experiences I’ve ever been forced to undergo, just to prove that I’m autistic enough. I’ve been diagnosed. I have significant challenges on a day by day basis. Why do I have to prove myself? Just because I look normal to you? Like seriously?

So I pitched the book. It was in January 2021, I think it was? Yes, January 2021 I was offered the book contract.

Carolyn Kiel: Wow!

Lydia Wilkins: Finished it in December of that year. It was turned in January, 2022, published last November. And to top it off, I managed to overturn the verdict of the benefits.

Carolyn Kiel: Oh!

Lydia Wilkins: So I got the support in the end. But it was just the thing of sort of, I was only really able to do that because I’m trained as a reporter. I have a law qualification. So in the end, it’s sort of like, I’m gonna run, I remember thinking, I will run rings around you just to prove a point, because I will not let you take this. You have to wait an amount of time, but during that time, you’re not given any support whatsoever. Not everyone can go for the benefit at the end.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: It’s something like 80% of everyone who’s told they aren’t eligible have that overturned anyway.

Carolyn Kiel: Oh!

Lydia Wilkins: It’s such a waste of time. Like it’s so costly. It was one of those things where sort of like, Lydia gets cross, Lydia decides to do something about this! And so I spent much of the lockdown writing that, and it came out last year. That’s how that happened. I never thought I would write a cookbook. I did not anticipate writing it. Generally speaking, I thought that I would never really write books, to be honest. That’s what proper journalists do. I’m not one of them!

Carolyn Kiel: Really, based on your own experiences, and it sounds like you found other people who had similar challenges, who were autistic, in cooking, specifically, in that you’re able to create this autism-friendly cookbook that helps really make it much more accessible to autistic people. What is it specifically about your book or, or the recipes in the book that makes it more accessible to autistic people?

Lydia Wilkins: Okay, so the caveat to this being this is a spectrum. And I feel frankly like screaming that. It’s also why it’s called The Autism FRIENDLY Cookbook. I’m on the autistic spectrum. I spent ages researching ways to help. It’s also for reference, it’s not supposed to be read from front to back. The amount of criticism I’ve had over this is from autistic people who have not read the nuance on this, have not read it properly, and have sent me quite sort of horrible messages, sort of going, you don’t speak for us all.

The thing about this is, so there’s part one and there’s part two. Part one is designed to kind of spell out why there may be access challenges. So explaining about interception, vestibular, all the different senses, the sensory profiles, how to adapt your kitchen. So if you struggle with jars, for example, why is it that parents always say things like, “you just have to learn.” Why can’t we just adapt and have a jar opener, for example? It will change your life, I’m telling you. There was all sorts of different information like that. The second part is a hundred recipes. So breakfast, lunch, dinner, and miscellaneous recipes. 30 of those are from other autistic people who I interviewed for the book. It’s also illustrated by Emily, who is on Instagram. She is at 21andsensory. She is an illustrator by trade. So it has a metric, so a coding system for dietary needs, sensory needs, and all the rest of it.

I’ve adapted the recipe format, so rather than, very often when you read, I don’t know, Nigel Slater or Nigella Lawson, whenever you read those sorts of books, it always has ingredients that you just somehow have to find halfway through that you had to put in. And it gets really quite stressful. It’s not a bad thing to have all of your ingredients lined up. I would argue that’s just logical. And yet autistic people are pathologized for this incorrectly. It’s not a crime to think a bit differently. It has different adaptations. The book has all the different sensory needs. The recipe format has been rejigged. I’ve tried to make it as accessible as I possibly can. It won’t fit everyone because you cannot fit everyone. I also cannot speak for people who have different neurodiversities. I do not have ADHD, for example. I will not speak for you. So I’ve tried to adapt the format of the recipes best, best I can.

And it also has for parents, teachers, and everyone else, it has all the different information about kind of strategies I guess you’d call it. It seems like parents always ask me, for example, they say things like, “my child is so fussy, they will not eat!” One of the strategies that I always point to is to change the format of the meal slightly, if you can realize what the sensory issue behind that is. It’s also so highly gendered. It’s always the little girl who is, they are entitled, they’re being bratty, they’re being princessy. Just change the format of the meal. Like unless there’s a serious issue, like they probably will start eating that. It’s a sensory thing. It might be the crunching sound. It might be the kind of the soft squishiness of a potato. I don’t know. It’s worth investigating and finding out rather than just assuming that they are the problem. We are not.

Carolyn Kiel: As you said, you can’t possibly cover every particular access need because autism is such a spectrum. But it sounds like you really look into those common challenges that a lot of autistic people might have around say, sensory and eating, or planning, or even like motor coordination and some suggestions on how to help with that.

Lydia Wilkins: There’s a lot on executive function in there as well. That always is not considered in the kitchen. It’s the thing of how do you sequence meals. So if you are cooking two different things and one needs to be in your cooker for, I don’t know, say 20 minutes longer,

Carolyn Kiel: mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: How do you sequence it so that they come out both perfect at the same time?

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: That was the most sort of common issue. Because even in the language I have tried to adapt as much as possible. There was one interviewee who expressed her frustration. So if you turn a cooker on in the UK, if you read the language literally, if you are boiling water, so you turn the hob on, if you read it literally, the temperature has been given an equivalent of mass. It just, it doesn’t make sense if you read it literally.

But what was really quite surprising is the amount of non-autistic people who were like, “oh my God, I read your book. It’s amazing!” Because it adapted to things that they had had an issue with as well.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: So when I started to ask them about this, because it was so interesting, they started to say things like, “the language in traditional cookbooks has always confused me.” So in the back of my book, there is a list of cooking terms, because who on Earth knows what things like Bain-marie are? Like. we don’t know that, we have to Google it, so it needed to be in there for reference!

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: What is the point of getting a cookbook if you don’t know what it’s telling you? There’s not much to that. You are just gonna be hungry by the time you are like, you know, having worked out all these ridiculous terms!

Carolyn Kiel: Or you’re not gonna use the cookbook. You’re gonna like, just set it aside and forget about it.

Lydia Wilkins: Most households have a load of cookbooks that, you know, sort of in-laws have given you for Christmas that just get abandoned on a shelf. Maybe we should question why this is.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. I feel like one consistent thing that autistic people ask for is clarity, and it’s part of like asking questions and just trying to make things very understandable. But of course when you’re very, very clear about things, it kinda helps everybody because everybody else is maybe kind of just trying to guess or like, “oh, well I don’t really understand that, let me just do something that I think is right.” But having, being very clear about is like, oh, okay, now I understand what to do with this.

Lydia Wilkins: I mean, surely that should, that’s just the basics of just sort of being a decent person, I always thought. Like, I have had multiple bosses who have been terrible communicators, enough so that other members of the team have always had to ask for further clarification. I will never forget the one boss who, she actually made me cry. This is a totally different person. I was working for her during the lockdown, and it was the thing apparently, she said this wonderful phrase, “just communicate better.” I’m not being funny. Statistically, but, so I process 40% more information than a neurotypical person does on a day by day basis.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: I think that’s a superpower in itself. Like I’m always translating. She had frustrated and made other members of the team also cry.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: So it wasn’t just me. And yeah, apparently it was the, that’s ableist to sort of, let’s just say to the autistic person, just communicate better. I wouldn’t be me if that was the case. I try my best!

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: But just, it’s even sort of the basics of sort of good writing, isn’t it? If you think about it, good writing is good writing on the basis of, it’s clear and everyone can understand it. Style, that’s arguably style. We are so culturally sort of ridiculous over the idea of it’s a special accommodation. It should be standard.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: I tried my best to do it. It might not suit everyone in the sense of, this was attacked by individuals, for example, for not being inclusive of every possible neurodiversity.

Carolyn Kiel: Oh.

Lydia Wilkins: Yeah. I had this wonderful experience of being asked, “why is it not the neurodivergent cookbook?” Because the access needs clash. Someone who has ADHD versus ASD are two very different things. You cannot possibly write this!

Carolyn Kiel: That would be an entire series, like a whole encyclopedia full!

Lydia Wilkins: And nobody would print it!

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: No publisher would take the gamble or investment on printing such a book, just because it would be terrible.

So, in the sense of, to come back to kind of the question almost, I think clear communication is needed. However, it’s also used as a tool to be obstructive, and I think we need to be wary when that happens.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. I think people don’t, in general, don’t realize just how difficult communication is. Like me as someone who studied it, and I’ve worked in areas where we are communicating, it’s so easy to think you’re being clear, and the other person, because they don’t have the context that you have or the basis of knowledge, or they’re just, their head’s in another place, they’re thinking about something else and they’re distracted, just totally your message doesn’t come across. And that has nothing even really to do with autism or neurodiversity or anything. But people think communicating is easy and it’s, it’s very difficult. So clarity always helps. And it sounds like that’s something you really brought to your book.

Lydia Wilkins: I’ve tried my best to! There are a few journalists that I know and they are, I don’t understand why, they would be unnecessarily combative with an editor. Everyone needs an editor.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: Um, they need a sub-editor, they need the editor-in-chief, they need everyone who’s overseeing your work.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: To make it good, to make it good writing.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: I don’t understand when other journalists, they’re like, oh, oh, balls to that! And all sort of things.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: It’s just so bizarre.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, I think the skill of being a good editor is really underrated.

Lydia Wilkins: Honestly, a good editor is worth so much.

Carolyn Kiel: Wow. So yeah, that’s great that you’ve got the cookbook out, and you mentioned that the first part is about some of the general accommodations or things that make things clearer in terms of helping autistic people in the kitchen. And then second is like a whole range of recipes.

And I think you also have a section in there, one for autistic people who are cooking, but also for, you know, family or people who support them in ways that they can help support autistic people in cooking. Is that correct as well?

Lydia Wilkins: Yeah, so that’s in part one, that’s one of the early chapters and that’s in the respect of very often parents ask me, what can we be doing?

The second thing about that is very often in the sense of if somebody has a comorbidity, there is a variety of access needs. Again, this is something that I just find sort of, to be honest, utterly bizarre. Help needs to be consensual. It needs to be consented to. And yet, as soon as you tick the box that says I’m different in society, that autonomy and agency is very often taken away.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: So I remember for example, even in education or even just sort of when relatives would teach me, it was always their thing of, “oh, just let me do it. And it will save you so much time.” They wouldn’t have said it to someone who was not on the spectrum by any means. There was an insidious idea of, you cannot let us fail because apparently we are fragile beings almost.

Carolyn Kiel: It’s a weird conflict between “why don’t you just learn” and, “oh, let me do it for you.”

Lydia Wilkins: Yeah. The amount of hoops that we have to jump through and the kind of the double stacked expectations almost, it’s, this is just to make the point, in the UK for example, so if you have any help from the state, apparently you are a scrounger. I say apparently because that’s not true. Apparently you are a scrounger if you have any disability support whatsoever. However, if you are working and if you earn a salary, you are apparently therefore selfish. The double stacking of this, I don’t understand. It just sort of, it’s ridiculous. We are neither of these things at all.

We are not a monolith, we are multifaceted human beings. Disability as a whole kind of concept is used to be reductive in the sense of how other people view us.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: It’s even things like, I recently had a, I guess you’d call it a friendship breakup, I think, where it was that thing of, I am a person outside of my disability.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: So I have other interests. Most of the time I don’t even talk about autism. It’s only sort of with the book that this has sort of become bigger in sort of like my time that I give to people.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: So in, such as in talking to you. I don’t specifically write about ASD or neurodiversity. I cover disability and social issues.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Lydia Wilkins: And it was that thing of, when I had to sort of start to explain to this friend that I am more than just that. So I’m still autistic, but I’m allowed other interests.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: I’m not their ridiculous perceptions. It’s, it’s even things like the question I get asked most, people are really quite entitled to ask sort of invasive questions at the best of times. It’s always things like, “oh, how do people like you date? What does that look like?”

Carolyn Kiel: Oh!

Lydia Wilkins: Like neurotypical people probably? Like, it’s not something new that we’ve invented.

Carolyn Kiel: We’ve been doing it the whole time.

Lydia Wilkins: Yeah. It’s not, it’s not something dirty. It’s not something secret.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: It’s just sort of, it’s even things like the assumption from this particular friend was, oh, Lydia would only date an autistic person because it’s keeping that within the gene pool. One, there’s eugenics. Two, it’s a perception. And three, like I’m a person! It’s even to the point where she thought I would only be attracted to autistic people? It’s nuts!

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: Like, what? It just sort like, I don’t remember talking this of her and sort of trying to unpick this. It sort of, it made my head hurt. And sort of going, maybe I don’t wanna be friends with you. Because, this is just to make the point of sort of this weird perception. We are multifaceted human beings. We are not a monolith when we are not just some sort of singular stereotype. I don’t understand why that’s so hard to comprehend. It’s just that doesn’t get said about any sort of any other characteristic. So why neurodivergence? Beats me.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, it’s always surprising when you think you know someone or you’re in the middle of a conversation and then something like that comes out. And you know, sometimes you can help change people’s minds, but not always.

Lydia Wilkins: All of what she said was offensive. And there’s an assumption on us to do the emotional labor of explaining it.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: As I’ve gotten older, I’ve started to say I’m opting out of that. It’s emotional labor.

I was listening to a podcast recently with a British writer, a feminist called Caitlin Moran. She wrote a brilliant book called How to Be a Woman. And she pointed out that the unpaid emotional labor of middle-aged women in the UK in terms of the gross domestic product that’s worth a continent like Asia in terms of equivalences.

Carolyn Kiel: Wow.

Lydia Wilkins: That was shocking to me. But I would argue that there’s an extra bit if you have a disability, but it’s always all the time I’m having to explain and sort of justify myself. I shouldn’t be. It’s always that thing of, “oh, we just wanna help you.” No, you don’t. You just want to feel good about yourselves.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: I will ask for help if needed. So if you are not going to pay for the emotional labor, that’s it. Like we are not walking talking resources.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: We are allowed to exist just as ourselves.

Carolyn Kiel: Plus, there are so many resources out there, you know, with the internet, with books that they can buy or even they’re free. If you wanna learn about something like that, you don’t have to ask specific people.

Lydia Wilkins: Well see also The Autism Friendly Cookbook, out now at all good bookstores! Like I get told off for saying that, but people so very often come to me with quite ableist questions. There was a guy who landed in my inbox, he said he wanted to do a story. Didn’t ask for permission to interview me and just lobbied these questions at me. Hadn’t even bothered to research. And one of them was, it was, it was a question, I forget how he phrased it, but it was basically, “what’s the difference between cooking for a verbal versus nonverbal autistic person?” Forgive me for saying this, but the last time I checked, whether or not somebody speaks doesn’t determine what they like to eat. If you are nonverbal, you still need to eat. It does not impact your preferences. It does not impact your sensory profile. Like that’s so ableist! You’ve not done the research. You’ve written to me saying, “I’ve found your book,” but you’ve clearly not read it because you wouldn’t be asking such a ridiculous question. Have you ever seen or met one us? Have you ever interacted, spent any time with us?

And I wrote back to say, “this was really rude, this question. It’s entitled, do you think you’re entitled to ask this, having been offensive?” And they did not really quite understand, but they wrote back saying, “oh, just scratch that off the list,” effectively. How about, I’m not answering the questions and you can go and research. Maybe go and buy my book for a start. It’s just sort of, there’s an emotional labor to this and I’m tired of the expectation. We should not be having to do this anymore. It’s 2023.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. Again, so many resources that are already out there that people can reach out to and educate themselves and read.

Lydia Wilkins: Read a book and ask questions later.

Carolyn Kiel: Exactly. Yeah. They need to do some research upfront before you just go out with like your whole list of questions.

Lydia Wilkins: Yeah. Don’t get me wrong, I’m happy to answer questions if they’re asked in the right context. So like I’m doing to you with this.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: I will say the thing about researching this book, when I looked for a cookbook that was autism friendly before I pitched it, there are books, articles and all the rest of it of basically: ah, cure your autism just by eating right! And don’t eat this poison!

Carolyn Kiel: Oh boy.

Lydia Wilkins: It is pseudoscience. It is offensive. And also like, seriously? Curing? I just, I’m not really sure how to begin with any of this.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Lydia Wilkins: But there was, it was basically people who were like, “oh, autism is such a tragedy, but it’s so inspirational when they reach such milestones.” Why can’t we just be seen as we are? Just as a kind of radical idea. And you are taking the enjoyment out of what should be quite an enjoyable activity. Food is to be enjoyed. It is pleasurable.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. There, there’s so many misconceptions out there.

How can people get in touch with you if they wanna read more of your writing or, or what’s the best way for them to follow you and learn more about what you write?

Lydia Wilkins: I am on Twitter and I’m also on Instagram, so that’s journo_lydia. So I will give you my details later on, so you can put these in the show notes.

Carolyn Kiel: Yes.

Lydia Wilkins: I am also on Substack. Again, I will give you these details. If you Google me, there’s also my website, so you can see kind of writing and all the rest of it. In terms of the book, the book is available pretty much anywhere. It’s just not in book shops, not physically when you go into a store, for example, but you can order it online. So it’s on Amazon, it’s on Barnes and Noble. It’s pretty much any bookshop that you can think of. You can also buy it from the publishers. I will probably email after this episode going, this is also another place that you can contact me!

Carolyn Kiel: You can send me the links afterwards. I’ll put them in the show notes so people can just click right on them from there, including how to get the book.

Lydia, as we close out, is there anything else that you’d like our listeners to know, or anything that they can do to help or support you?

Lydia Wilkins: If you wanna support an autistic person, just start asking us questions about what our access needs are rather than just assuming you, the neurotypical, non-disabled person know already. We should not be spoken over. So we need the sense of agency to be given back to us. We should not be having to abdicate our autonomy. We are just people like, you know, we’re just human beings and yet very often we end up dehumanized.

If you wanna learn about us, start by reading books by people like us. Don’t go for the terrible, kind of like, ah, cure yourself from, you know, don’t eat this brain poison, or whatever the term is. Don’t go for the anti-vaxxers. Don’t go for the autism mom Facebook groups. Engage with us. We are not scary. We are just part of this rich tapestry of just different people, at the end of everything.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, absolutely. Really important things to keep in mind. All right, well thanks Lydia. It was great talking with you. Thanks so much for being on the podcast.

Lydia Wilkins: And thank you for having me.

Carolyn Kiel: Thanks so much for listening to the show today. Okay. Here are the details for the book giveaway. Beyond 6 Seconds is running a giveaway for two lucky listeners in the United States to win a free copy of Lydia’s book, The Autism Friendly Cookbook. Check out my pinned Twitter post on Monday, July 24th, 2023 for how to enter. I’m at Beyond6S on Twitter. I’ll put the link in the show notes so you can go right there. The giveaway ends at 11:59 PM Eastern Time on Friday, August 4th, 2023. Up to two winners will be selected at random. This giveaway is valid for listeners at US addresses only.

Thanks for listening to Beyond 6 Seconds. Please help me spread the word about this podcast. Share it with a friend, give it a shout out on your social media, or write a review on Apple Podcasts or your favorite podcast player. You can find all of my episodes and sign up for my free newsletter at beyond6seconds.net. Until next time.