During this episode, you will hear Kelly talk about:

- Growing up with two autistic brothers – and how she got her autism diagnosis

- How Kelly learned she is autistic – a year after her parents and teachers already knew

- Her autism advocacy – and why she likes answering people’s questions about autism most of the time

- Life as an autistic college student

- The story behind her novel, All Ways, and how it counteracts common literary narratives about autism by centering autistic experiences and voices

To find out more about Kelly and her work, you can find out with the links down below:

Subscribe to the FREE Beyond 6 Seconds newsletter for early access to my latest podcast episodes!

*Disclaimer: The views, guidance, opinions, and thoughts expressed in Beyond 6 Seconds episodes are solely mine and/or those of my guests, and do not represent those of my employer or other organizations.*

The episode transcript is below.

Carolyn Kiel: Hello, and welcome to the Beyond 6 Seconds podcast. I’m your host, Carolyn Kiel. And on today’s episode, I’m very excited to be speaking with my guest Kelly Coons. Kelly is an autism advocate who studied English at Smith College. Before Kelly was diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder at the age of 13, she had a coming of age story that was mostly deemed as neurotypical. However, she always felt isolated and until her diagnosis believed that she was to blame. After her diagnosis, Kelly became passionate about disability advocacy and promoting autistic pride. Kelly, welcome to the podcast.

Kelly Coons: Hello!

Carolyn Kiel: I’m so excited to learn more about your story. You know what it was like growing up before your diagnosis and then what things were like afterwards and all of the advocacy and things that you do.

So you were diagnosed as autistic when you were relatively a young teenager. So what was life like growing up before you knew you were autistic?

Kelly Coons: So I have a unique perspective on this because although I wasn’t diagnosed until I was 13 and a half technically, but nobody counts a half year. My two brothers were already diagnosed as autistic. My younger brother was diagnosed at age two. And my twin brother was, he had a PDD NOS diagnosis for awhile, Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified, also known as, we don’t know quite what’s up with you, but not neurotypical. And I think that crystallized into ASD, maybe mid elementary school.

But as a result of my brothers already being diagnosed, a lot of my family’s social activities were based around you know, connecting with other autistic kids and also other like parents of autistic kids. So it wasn’t like I had no idea what that was or I was like, am I gonna die? Like, I, I knew what autism was. And even in the two examples of my brothers, nevermind all of the people I saw growing up, I saw how autism was, could manifest very differently.

So I think of it kind of like a, like a double identity, like I was in these spaces. But all the time, I was like, well, you know, I don’t want to step on people’s toes. This isn’t, this isn’t my space. This is, this is for them. And then I’m supposed to have people over here. Nevermind how I didn’t really have people over here. But I think even as a kid, I was very conscious of trying to give people their space.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. So when you were spending time with, you know, your brothers and, you know, the autism community, did you ever feel like a commonality with them? Like, oh, I really relate to people, or was it just sort of trying to find your way in the world?

Kelly Coons: Yeah. This is, this was a conversation that happened like after I was diagnosed. When my twin brother and I were in high school, there was a conversation at like a cafe. And it was with two of my brother’s friends. For reference, my brother went to a boarding school that mostly served autistic and students with ADHD. So like most everyone was autistic and if they weren’t autistic, they were in some other way neurodivergent. So the culture was very much, you know, let’s just talk about this, which is like one of my favorite environments, like I’ve ever encountered in my life.

I’m like, if there is a paradise, it looks like people just talking to each other the way people do at this school. But they were like, “Yeah, everyone knows that people with autism don’t like sandwiches cut into squares. They like sandwiches cut into triangles. It’s a well-known fact.” Not a well-known fact. Citation needed! But like they were just talking about the being upset about how the sandwiches were cut and then just nodding along, like, yeah. Yeah. And here’s the wild story. Enough people complained about how the sandwiches were being cut, they talked to the cooks and they were like, okay. And then they started cutting it into triangles. And the whole community was like, “yes, a victory for all of us!”

Carolyn Kiel: Like, you know, and it’s, it’s funny. But it, it, in some ways, you know, there is kind of a view in society of autism and autistic people as just sort of being, I don’t wanna say like monolithic, but like everybody is the same. They’re very like specific about the types of foods that they eat or that, but that’s not even, that’s not necessarily true for everybody.

Kelly Coons: Yeah, no, I’m sure there was one person who was like, “oh but I like the squares! And now I’ve been outed as a minority in this space.”

But I think, I think that story also shows how. I think there’s a lot of depiction of people with disabilities in general, nevermind just autistic people, as kind of like passive and you know, maybe they have feelings, but they’re never going to vocalize them. But in this story, no, they were upset about the sandwiches and they demanded that they be cut properly, and then they were.

Carolyn Kiel: I think that’s great. They were able to affect change. There’s enough people who wanted things changed. So then, you know, you grew up with two brothers who got autism diagnoses, I guess, relatively young in life, or perhaps younger than you at least. So how did you find out that you are autistic?

Kelly Coons: So there’s two parts of this story. One where I get the diagnosis and two, where I am later told about the diagnosis. Spicy, I know!

So I going into high school I had some trouble at public middle school. Nothing, I mean, there are terrible horror stories. Mine, wasn’t a horror story. Mine was a, oh my goodness, there are like too many people in the classroom, too many people to like keep track of, like, I don’t think I can go to an even bigger school. And by bigger, I mean just more people in it. The size of the building actually probably stayed about the same, which made the people density population actually way worse than middle school.

And my family had the means of looking at other high schools as an option. So I was talking to a like educational consultant and apparently within the first five minutes, like she clocked something about me and then said to my mom, “oh has like Kelly ever been tested?” And my mom was like, “aw, but my normal one!” Which she agreed to doing it because this wasn’t her her first rodeo, but there was kind of a little bit of sense of “oh man, come on. I thought, I thought we were done with this.”

So I decided on my own that the reason why I was being taken out of school for the day was that I was like the smartest person on the planet. And this was actually colleges wanting to get information on how smart I was. Now, this was not something my mother told me, but this was something I told her and she just kind of nodded along tacitly agreeing or disagreeing or saying nothing, which meant to me, “oh yeah. I figured out what’s going on because I’m the smartest person on the planet.” That was not what was going on. For people who’ve done neuro psych evaluations, they are an all day affair. And even it technically doesn’t take up all of the school day, but you’re so exhausted afterwards that you’re not going back to school afterwards. And even if you were to sit in the classroom, you wouldn’t be absorbing anything.

So I remember doing these tests and there was one test in particular, I think it was like a visual spatial one, where you had to put like blocks together to make a full shape. And I had a feeling I bombed this one and I was like, “oh God what are the colleges going to say?” Mom just nodding along at lunch during the lunch break. Like, “oh man. Well, don’t worry. There’s more tests though.” Just trying to say something to not affect my results and not reveal what I was actually doing, but enough to like, make me not give up. But yeah, so that was, that was the diagnosis that happened.

But I wasn’t told about it until about a year later, which also has somewhat of a funny story. I was in an English class and they were like, write a personal narrative. Which, you know, there’s nothing more teenagers like to do than to write about their lives, which are, you know, like I’m not going to say teenagers’ lives aren’t difficult, but there’s a certain amount of at that age, when you feel like you have reached the peak of your experience, which is just not true, regardless of how interesting your life has been, but you feel like you’ve, you’ve reached the pinnacle. So. So I was like, “oh, I’m going to write a personal narrative about my life having autistic siblings.” And I thought the narrative was going really well. My mom was reading, reading it because I wanted to confirm some like numbers and stuff with her. And she was like, “oh, you know, you’re autistic too.” She was apparently not supposed to have said that because she said it and just kind of went, oops! And I was like, “really, I gotta change my narrative now!”

So what I didn’t know was at that time there was debate between my parents and what do we do with this information? It was sent to the school because teachers presumably had to know, although I think it is kind of messed up that apparently a teacher is more deserving of this information about how a student is supposed to work, then the student themselves. So apparently all the teachers knew.

If I had written an essay about how hard it was to have autistic siblings and I hadn’t been told, and I had written sent the original version on, the teacher would have read it and been like, “I guess she doesn’t know!”

Carolyn Kiel: Wow.

Kelly Coons: There was debate. My dad in particular took the side of, “I don’t want her to be discouraged by this information. And so, you know, to keep her morals up and to not have her worry about what that means we should, you know, conceal it. She shouldn’t feel limited by that.” Which is a perspective I can understand in so far as I’m like, I understand there were good intentions here, but do I understand it in so far as it’s actually a good standpoint? No. My personal opinion of diagnosis is this. Once you have a diagnosis, you can choose to share it with who you want or who you don’t want. But if you don’t know that information, you can never make an informed decision about what to do with that information.

So I was diagnosed at around 13 and a half. I didn’t know about it until I was about 14 and a half. So I was still a young teenager. But yeah, there’s still emotions I’m grappling with, with that point in time. And I am aware that I have the fortune of that kind of in-between space only being a year, but a year is still a lot, especially when you’re a teenager, there’s a lot that changes between 13 and 14.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And I I’d imagine that. I, I think sometimes with people when children, or really anyone gets a diagnosis of autism, there’s the thought of, “well, you know, maybe, maybe we don’t say anything because they seem like they quote unquote, seem like they’re doing fine. Like they’re getting great grades and they seem okay in school, maybe have some small challenges.” But at the same time, nobody knows what’s going on fully in your own head as a person.

So. So I, yeah, I could see that as a challenge. I think people are afraid of like labeling and things like that, but in some ways the label was really helpful to understand like, oh, this is why I process like information this way.

Kelly Coons: And also a label means that you’re not the only person with that label. If a label exists, then there are other people like you, which isn’t to say that, you know, every autistic person’s gonna be best friends with every other autistic person, but there is a relationship of experience there. And that is something that is valuable.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And plus with the label you can get support, which is another big thing.

Kelly Coons: Yeah. If you don’t have a diagnosis, then you’re not getting you know, an IEP. You can have a harder time accessing counseling. Maybe the idea of, “I don’t want you to be limited,” could work in a, in a utopian society in the future where, you know, one doesn’t need to prove that they need support in order to get it. But we don’t live in that world, especially in the United States. So I, I think the idea of, “I don’t want to tell them because I don’t want them to feel limited” is a naive one.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And plus it sounded like you felt even before, before you knew your diagnosis or had the diagnosis that you felt somewhat limited in that you felt isolated or you just felt different and didn’t quite know why.

Kelly Coons: Yeah. I, I mentioned the story of how I randomly, apropos of nothing decided that I was the smartest person in the world, but it wasn’t quite apropos of nothing. It was realizing, oh, I, I get good grades at school, and people don’t like me. Therefore logic done of of an insecure adolescent is, oh, the reason why they don’t like me is because they’re jealous of my good grades because I am smarter than them, which is not a healthy way to deal with it. But was kind of a way to frame that isolation as something that wasn’t my fault.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. You’re trying to make sense of the situation, you only have some information.

Kelly Coons: With the benefit of hindsight. I can see, hey, maybe people didn’t like me because I was a tattletale or people didn’t like me because I just didn’t understand a lot of the signals they were trying to give. And some of those are, you know, more excusable than others. Like, I’m not sure if I on the outside looking in would have wanted to be my friend. But there’s still a certain amount of, you can recognize when you were in the wrong, but still say I was hurt by not being included.

Carolyn Kiel: Of course. Yeah. And especially if you don’t have, you know, with hindsight, you know, is, you know, even going into adulthood, you have time to reflect on your behavior and you just have more experience in the world about like, oh, I could understand how that came off differently.

But I think having the diagnosis really helps put a lot of things into frame because I think a lot of particularly autistic girls have those specific challenges around social dynamics. And sometimes we mask well enough to kind of get by okay. Where it’s not like glaringly, you know, obvious that, so, you know, we’re not always like the typical stereotype of just always sitting in the corner by yourself. .

Kelly Coons: Or, no, here’s arguably what’s even worse. When you’re in a group and you say something and it wasn’t meant to be funny, but then people start laughing and you’re like, “oh, okay. What do I do now? That wasn’t part of the plan.”

Carolyn Kiel: Like, “why was that funny?”

Kelly Coons: Yeah. Or you’re sitting there and you’re nodding along and you’re like “I’m nodding, but I don’t actually understand what you’re saying and I’m not sure if I actually agree, but I am nodding so I can be with the group.” I think sometimes that inclusion without, without understanding which isn’t the group’s fault, you know, for all they know you’re nodding along because you emphatically agree. It’s sometimes I think even worse than being by yourself, because at least if you’re by yourself you have some sort of understanding of what’s going on in your own head.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. So then, you know, with this knowledge of your diagnosis, how did your life change once you knew you’re autistic?

Kelly Coons: I think it was first of all, a lot of looking back on life, my 14 year old long life, because I don’t have memories of being a baby. People don’t. But looking back and being like, “oh, that makes sense.” Or “hang on, that thing that happened that wasn’t your fault.” The biggest emotion for me was kind of letting go of guilt, which isn’t to say not accepting responsibility. There is a difference. But being able to say “there are some things that are difficult for me and some things that I’m going to need to voice but that isn’t a failure morally.”

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And you know, just seeing your life in a different light, in a different lens, looking back. Yeah. And then shortly after your diagnosis, was that when you started becoming passionate about disability advocacy and promoting autistic pride?

Kelly Coons: Yeah. I think a lot of narratives around diagnosis lines about letting go of guilt. And I’m not saying that’s the only narrative that can be around diagnosis, but the dominant narrative of diagnosis, isn’t actually about the person receiving the diagnosis. It’s about the people around them. It’s about “I’m mourning the child I didn’t have.” And it’s like, well, no, a child who is autistic is going to be autistic, whether you are able to access the diagnosis or not. And also of people around them, even if it’s non-parents being like, “oh, but how do I treat them now?” Well, it’s the same person. Diagnosis is, you know, a magnifying glass. It’s still there, whether you see it or not, whether you choose to research it or not. It’s just with the magnifying glass, you can hopefully try to not step on the person in the way that that you might not be able to see otherwise.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And, and sort of a related point that you brought up with that is that a lot of the narrative tends to be around, or we tend to hear it from people who are not autistic, like relatives or parents or friends, or experts. But, you know, we don’t often get to hear stories from actually autistic people and talking about their own experiences. So I think that type of narrative is important too. Yeah. And so did you, I, I think I heard on another podcast that you actually were in your high school, actively helping to educate people about autism. Tell me about that.

Kelly Coons: After I got diagnosis, I was like, oh, like, now that I am certified autistic which there is a problem of self-diagnosed autistic people not being believed or not being seen as, you know, experts on their own condition. Like you are the expert of one thing in your life, and that is you.

If nothing else, you are an expert on that. People not realizing how inaccessible the mechanisms of diagnosis is, especially once you’re out of the school system or if you were never in the public school system to begin with. But yeah, once I kind of had permission in a way, and I don’t necessarily need permission from my parents, I need permission from oh, you know what you’re talking about sort of way.

I was like, oh, there is, there is kind of a need in the world in general, but also in my high school in particular that had a not insignificant portion of people accessing extra help services. It was called the learning skills program, and not every single person in that program was autistic, but there were a few that were. And in talking with a few of them, a lot of them who I actually knew from outside of school, in these aforementioned autism things, I encountered that of the people I knew well, I was the one who is most comfortable outing myself publicly in that way.

So I was like, oh, I’m comfortable talking about myself. I have somewhat of a reputation here of being a good student. So, so that helps too. So yeah, in my junior and senior year in high school, I did, my high school had kind of, but not once a week, like maybe two or three times a week, the whole school would meet in our little auditorium space and you could, people could go up and make announcements. You sat in the front when you wanted to make an announcement, there wasn’t really a vetting process. So there would be people who would say like “happy birthday” and that would be the announcement. Good job. Yeah.

So I worked with my learning skills program teacher because I also wanted some sort of faculty backing. And yeah, I was like, oh, it’s autism awareness month. Here are some people who you might know who maybe you didn’t know they were autistic. And the culmination of this month for the two years I did it was kind of a Q&A session, like, Hey, ask an autistic person and ask like an autistic peer, also, I mean, you can ask Google or you can look up, you know, some famous autistic person’s answer, but like, what does it mean to be an autistic person in high school? What does it mean to be an autistic person at this school?

Which one thing that looking back on, I wish I could have done was having more than one autistic person on the panel. But of the relatively small population of autistic people there, no one else wanted to do it. So it kind of wasn’t an option for me to, but it would’ve been really nice to have, you know, not only a white autistic girl, I was a girl then, but also perhaps like a person of color who was autistic. Maybe a person who came from a low income background who was autistic, which it was something to say that there weren’t, you know, as many people from a low-income background in my private high school. Now in the larger world, I think I have more of an understanding of intersectionality in this, not to disparage my past self, but to say, there are better ways to iterate upon this.

Carolyn Kiel: I mean, intersectionality is huge with the autistic community and the disability community, really just how all those different issues converge. It’s it’s big. And it’s good that you’re thinking about that, that now, because society needs to understand that better in general.

So you discovered this around age 13, 14. So you’re in high school at this point when you get your diagnosis. And then, now that you know that the test you took was not for college screening, what was the college search like? Like, did you take certain things into account about like types of things you were looking for when you were looking at a college? Size, stuff like that?

Kelly Coons: The high school I went to and the primary reason I went to that high school was because it was a college prep high school. They had a really good college counselor. So the idea of going to college from this high school was kind of a given of everyone had their after school things where we would work on the common app together. There were just regular meetings with the college counselor.

So unlike for a lot of people, the idea of I’m going to college was not a negotiable or even a thing that was debated, which for me, I, I wanted to go to college. I liked learning. But that’s a minority for people in general, but also for autistic people. A lot of autistic people hate school and do way better with the structure of the workplace.

But for me, I wanted to go to college and my high school kind of being built on college prep and having this built in learning skills program had experience with working with accommodations. Another point where I have a bit of a unique story is that I never accessed academic accommodations. That was never something that I had difficulty with. The types of accommodations I wanted were more social, which there isn’t necessarily a “be nice to me” badge that someone can flag. So, so the types of accommodations I wanted kind of didn’t exist, but you know, you work with what you got.

So I knew going in that one of the big motivations in me wanting to go to a private high school as opposed to a public high school was size. So not uncommon. I was like, I want to go to a small college, which most, any college you go to is going to be bigger than the high school you go to, even if it’s you know, a public high school. So I was like, okay, I want a small school.

I also want like, you know, walkability. I had a bunch of my friends who were like, oh yeah, I’m driving. And I was like, man driving is anxiety-inducing. I’d like to be able to go to a place where I can walk to where I need to be. I need to walk to CVS. I’ll walk there. I need to walk to campus. I’ll walk there.

I also wanted to live on campus because I was like, I want to have the experience of living, it’s not quite by yourself, but it’s not with your parents, which is great. So I was like small, walkable and residential life, which my parents also were like, “yeah, go live on campus,” which is not always a common experience for people with disabilities. But my parents were supportive of my goal to A go to college and B get out of their faces.

So one other thing I realized in talking with my college counselor was I had a lot of anxiety about kind of like party culture and like frat culture. I don’t want to go to a place with Greek life because even though I don’t want to be in Greek life, Greek life has a way of affecting the rest of the campus. Which isn’t to say that, you know, Greek life is always a negative, but it usually is a loud, even if it’s a good loud. So I was like, yeah, let’s, let’s pick a quiet school. I don’t want a party school. So I was looking for a place that didn’t have Greek life. And also at some point in the process, I was like, I can go to a women’s college. I don’t need cis men in my life to feel fulfilled. I say this with all the love in the world to my brothers. I don’t, I don’t need that. It’s okay.

So through processes of researching and visiting campus, I landed on Smith College. I remember the reason why I picked Smith College. I was down between Smith and Connecticut College. Very similar, neither of them had Greek life. Both of them were about only 2000 people. Connecticut College was actually I think a bit closer. But I went to Connecticut College and visited a music class that counted towards English credit. Sounds great. Right? Well, everyone was like dead in the class. No one was really paying attention. The professor like left for 20 minutes without explanation. I think there was some sort of tech issue going on and I get, it was cold and flu season, but like no one seemed to care. And that was demoralizing.

Then I went to Smith and I went to this Old English class. And despite the fact that it was an Old English class and they were doing like verb conjugations, which the worst part of learning any language is figuring out how it works. Before you can really communicate with words, you need to be like, okay, but how do these words work? Despite the fact that it was an Old English class and they were doing verb conjugations, everyone was into it. And I was like, I think it says something about this school that people even during once again, cold and flu season, are paying attention in an Old English class. Yeah. So I was like, okay, I can do that.

And my, my dad took me to this visiting day and he like drove around Northhampton. And I was expecting him to be, “ah, I’m not sure if you should be in this, this town full of only women,” which is not true. There are men in the city of Northampton and there are men on Smith College. Like there are professors who are men. So he told the story about how he was trying to get, get coffee. And like, there was only like boba tea, which is very Northampton, which I was expecting for the story to end with, “and then that’s why I don’t approve of you going here. Because where would you get your coffee?” Even though I’m not a coffee drinker, but he told this story and he was like, “despite that, I liked it.” I’m like, “oh! He’s like, “yeah, you can walk. There’s a pizza place. CVS is in walking distance” and I’m like, “now there’s a seal of approval!” So Smith College. CVS is in walking distance.

Carolyn Kiel: That’s it, you know, it’s funny. That is really helpful. Cause I, I went to Vassar and a lot of what you’re describing is, you know, a little bit, it sounds very Vassar at this point in terms of walkability and small college and no Greek life and stuff. So I relate to a lot of the stuff that you’re you’re sharing and yeah, it’s just a great, you know, if that’s what you’re looking for, it’s a really great place to, you know, type of environment to be to be part of.

So, now that you’re at college, I know you mentioned in high school, you didn’t really access any like academic accommodations. It was more around social. But do you feel like your needs are, are supported there, that you’re able to get what you need academically, socially, things like that?

Kelly Coons: Yeah. Yeah. I think the main thing is with the diagnosis in hand, and it’s not like I keep a copy of my diagnosis and flash it out whenever I need it. But having the autism diagnosis in a way it’s almost like a card you can flash when someone is. Like the explanation for, “Hey can you turn down the volume a bit?” If someone decides to be a jerk about it and be like, no, even though it’s a there’s 24 hour courtesy hours, but the solution to, Hey, can you please keep things down? Should always be ok, I’ll try my best. Sorry for bothering you. But if someone decides to be a jerk about that, as people can do, it can be like, well actually I have a psychological need for quietness, which is perhaps a bit of hyperbole. But sometimes if you need hyperbole to get by, that’s okay. So that was important. And being in a space where after revealing that autism diagnosis, it was like, oh, that’s okay. To have autism not necessarily be a shutting down of the conversation, but be like an “oh, you know, look at all the different types of people who come here!”

And even, you know, the questions of, “oh, well, what does, what does that mean?” Or like, “I have a cousin who’s autistic, but like, I don’t know, he seems different than you.” Which is like, well, yeah, if your cousin’s five and I’m 20, then yeah we should seem pretty different, right? But but those kind of well-meaning questions that as a person on the inside, you just kind of laugh at, like, well think about that question for a sec, and think about how silly that sounds.

Kind of my, my favorite thing, and I don’t think that’s a terribly uncommon experience in college. You know, someone who’s, you know, lives in Florida might get a question about like, wait, there are lizards where you live? In Northampton, there aren’t lizards. Everything would die in the winter. That’s not an experience that’s exclusive to being an autistic college student, but I think there’s kind of more of a, a power in those questions and someone’s comfort in asking those questions. And also the ability to answer those questions. Like learning there are lizards in Florida could be super cool, but like, does it change the world? Does it change your way of looking at people? I don’t think so. Unless if you already have a very strange way of looking at the world that is dependent on there not being lizards. But. Yeah.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, it’s good that people are open about asking those types of questions and listening and learning.

Kelly Coons: One of my goals in my personal advocacy, and advocacy can look so different depending on who’s doing it and what intersecting identities you have. One of my personal goals is making autism not something that’s scary. I’m not scary, right? I mean, I sit in my room and have a cat shaped pillow, you know, nice and approachable! Is making a space where those questions, even the really awkward questions that are okay to ask. I like answering questions. And you know, some days you just don’t have the energy and you can say, hi, I just had a final, can we shelve this question? Can you ask me later? And that’s an okay answer too. You don’t always have to be down for 24 7 answering questions, as no one is required to do. But in general, I like answering questions because now that you have that question answered, I think there’s a, there’s a power in kind of humanizing the situation or even just having a face to connect with it.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, absolutely. Yeah. I want to live in a world where autism isn’t scary anymore and I think we’re getting there.

So, you know, you’re talking about your advocacy and you continue with your advocacy now, and I definitely want to make sure we have time to talk about your writing. So, you know, you talked about in high school writing, you know, at first writing that story about your brothers and then about yourself, and now you actually have a young adult novel that’s published, that’s your debut novel. So tell me about the process around writing that and what that was like.

Kelly Coons: Yeah. So, you know, the summer of 2020 was a wild time. And I think for a lot of people, it was a time just kind of marked of, what do I do? There doesn’t seem to be an end in sight. I don’t personally have control over a lot of things. And I luckily had an opportunity to write a book. I was contacted on LinkedIn about a class and I was like, yeah, I have time for a class because my classes for school had all gone online. Yeah. I mean, what other time am I going to have time to write a book? So I was like, okay, let’s do it.

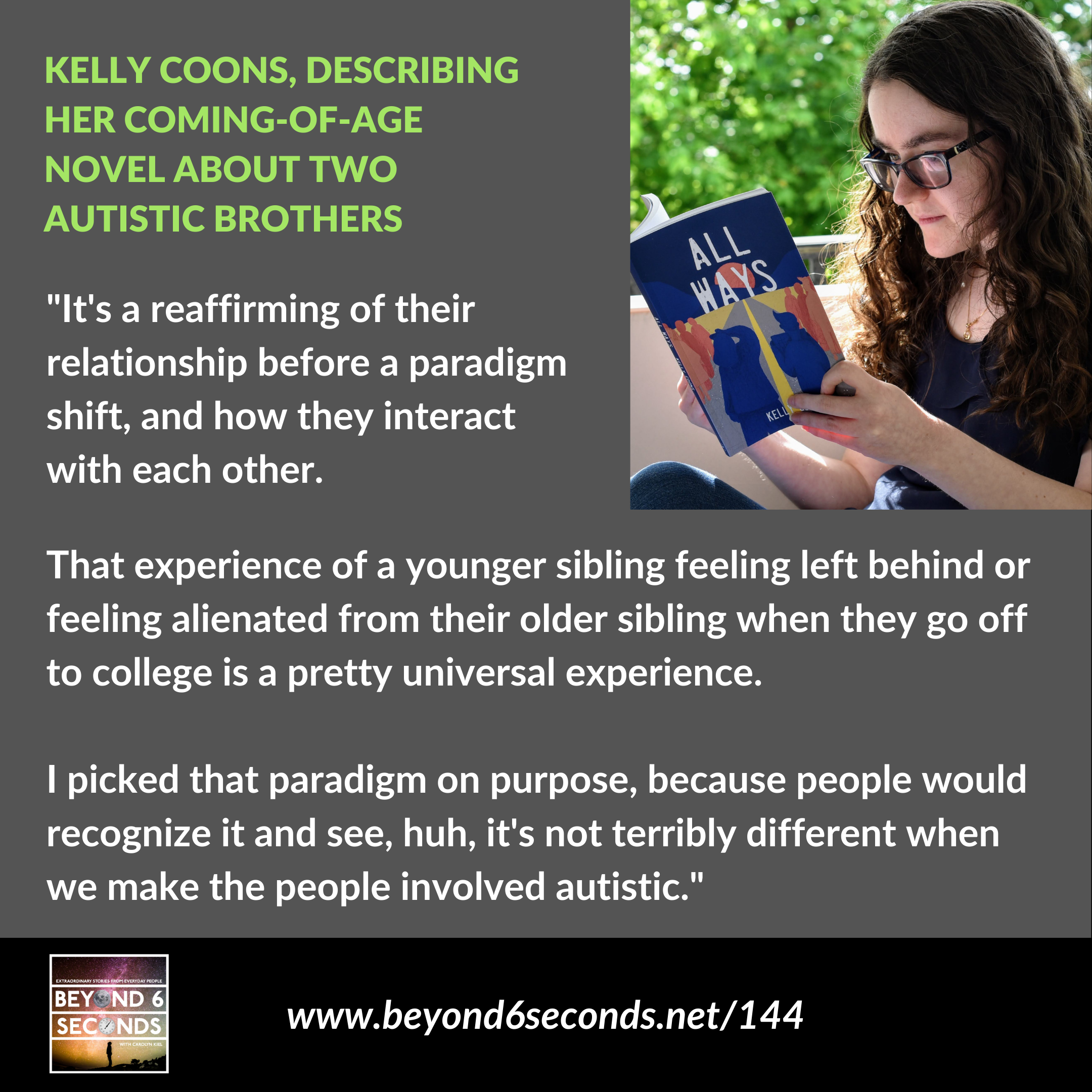

It’s funny, you mentioned, actually it’s just funny in general, that we talked about me writing a story about brothers, because my novel All Ways is about brothers, two autistic brothers. York and Andreas going on a road trip together. And it is correct that the very base of them is based on my own brothers. But they’re not inserts for my brothers.

I started with using my brothers as a base to make them realistic and to give them a rapport with each other. But from there, I was like, what kind of story do I want to tell? What kind of traits help this story? And also just a good old switcheroo. Sometimes I’m like, here are some traits. This is a trait that exists in my younger brother, but let’s give it to the older brother. That’d be fun. So, enough so that when I showed my, my twin brother, the book, he said, it’s not about me. I’m like, well, no, it’s not about you. It’s about York and Andreas, Andreas and York. York’s somewhat based on you, but it’s not you, you can rest assured of that, my good sir!

Yeah, I wanted to write kind of in a form of advocacy. Kind of a backwards facing or a past facing form of advocacy. The books I read growing up about autism really weren’t about autism. They were about a neurotypical character kind of looking at an autistic character and being like, “man, their life sucks. I’m so glad that I’m not that. I really appreciate what I have.” Which is a really bad message if you’re the autistic person, or even a person who loves an autistic person and you’re like, oh, oh, okay. That’s really not helpful for the person who can’t change their autism or their disability or their, whatever. That’s, that’s very unhelpful to them. And it kind of implies that that population couldn’t possibly be reading this book. So I was like, I’d like to write a young adult novel about autism, that the protagonists are autistic and the conclusion isn’t “man, autism sucks, so glad I don’t have it.”

Carolyn Kiel: That’s awesome. Yeah. I mean, and so in terms of the plot of the story, it’s like they go on an adventure.

Kelly Coons: Yeah, it’s, it’s coming of age. York got accepted into college and he’s like, I want to go on one last hurrah, not one last hurrah like he’s going away forever, but one last hurrah before I move, I don’t live with you for at least four years. It’s a lot of a reaffirming of their relationship before a paradigm shift and how they interact with each other. And that experience of a younger sibling feeling left behind or feeling alienated from their older sibling when they go off to college is I think a pretty universal experience. And I kind of picked that paradigm on purpose because people would recognize it and see, huh, it’s not terribly different when we make the people involved autistic.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. I think it’s really important to have narratives published like those that you’re hearing directly from autistic characters. I’m seeing more and more sort of like memoirs from autistic adults who are writing about their lives. So we’re starting to hear more of that first person, but even, you know, in fiction, it’s absolutely important to have those first person narratives from autistic characters, disabled characters, really all kinds of characters.

Kelly Coons: And disabled authors.

Carolyn Kiel: Yes.

Kelly Coons: I don’t think I could have, the story might’ve existed in my mind, but I would not have published the novel if I, A hadn’t gotten my diagnosis, and B didn’t know about it.

Carolyn Kiel: Definitely. Yeah. That representation in writing and literature and really all sorts of media is really important.

Absolutely. Wow. And then, oh, and the name of your book is All Ways, is that right?

Kelly Coons: All Ways, two words.

Carolyn Kiel: Very cool. All right. Awesome.

Kelly Coons: There’s a fun backstory behind the title. So I live next to the American School for the Deaf, not next to, as in right next to, but in the same town. And the slogan for the American School for the Deaf is All Ways Able, All Ways two words, so in all the ways that we do things, but we’re also able, always as in all the time.

So I was like, oh, that’s a clever pun. Which York and Andreas are not deaf. And there aren’t any deaf characters in the story, but I think that kind of, that kind of wordplay of always temporality, but also all ways in different modalities is, is valuable in a lot of different contexts. So I was like, yeah. Yeah, that works.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. No, that’s perfect. That’s a great way to think about it. Absolutely. Wow. So yeah, I mean, Kelly, I’m checking the time, the time has flown since we’ve talked, I’ve just so enjoyed talking to you about your story. Tell me, how can people get in touch with you if they want to buy your book or just learn more about the advocacy that you’re doing?

Kelly Coons: Yeah. All Ways is available on all major online retailers. Amazon, I have it on Barnesandnoble.com. I’m working on getting it into in-person bookstores. But I don’t know who’s listening in from and where so online is just easier to tell people. I have a website Kelly, Kellycoons.weebly.com of which on the All Ways page I keep track of all places where All Ways is available. I also have a little blurb about myself. I also put all my social media pages on there. I’m on Facebook and LinkedIn and Instagram. So I’m available in a, in a lot of places.

Carolyn Kiel: Right. Fantastic. Yeah. And I’ve got a link that you sent me that has sort of where they can find your book and more about you. So I’ll put that in the show notes too, so people can find you there. Very cool. So, yeah, as we close out, is there anything else that you’d like our listeners to know or anything that they can help or support you with?

Kelly Coons: If you read my book, leave a review, please. If you’ve talked to any authors, especially indie authors they’ll say that. And it’s true. I mean, it doesn’t have to be a five star review kind of there’s also a value in a more critical review that talks about what things could have done better. Yeah, it’s, it’s kind of like a little, you did good or you could do better. And both of those are valuable.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. Great. Yeah that feedback definitely helps. Wonderful. Well, thanks so much, Kelly. It was great talking to you and I loved learning about your, your story and all of the great advocacy and, and writing that you’re doing. So, thanks again for being on my show.

Kelly Coons: You’re welcome.

Carolyn Kiel: Thanks for listening to Beyond 6 Seconds. Please help us spread the word about this podcast. Share it with a friend. Give us a shoutout on your social media or write a review on Apple Podcasts or your favorite podcast player. You can find all of our episodes on our website and sign up for our free newsletter at www.beyond6seconds.com. Until next time.