As a child, Ariel Henley remembers when her face was compared to a Picasso painting.

This insult didn’t come from a schoolyard bully. It was written in a magazine article about Ariel and her experience growing up with Crouzon syndrome, a congenital condition that affects the shape of her face.

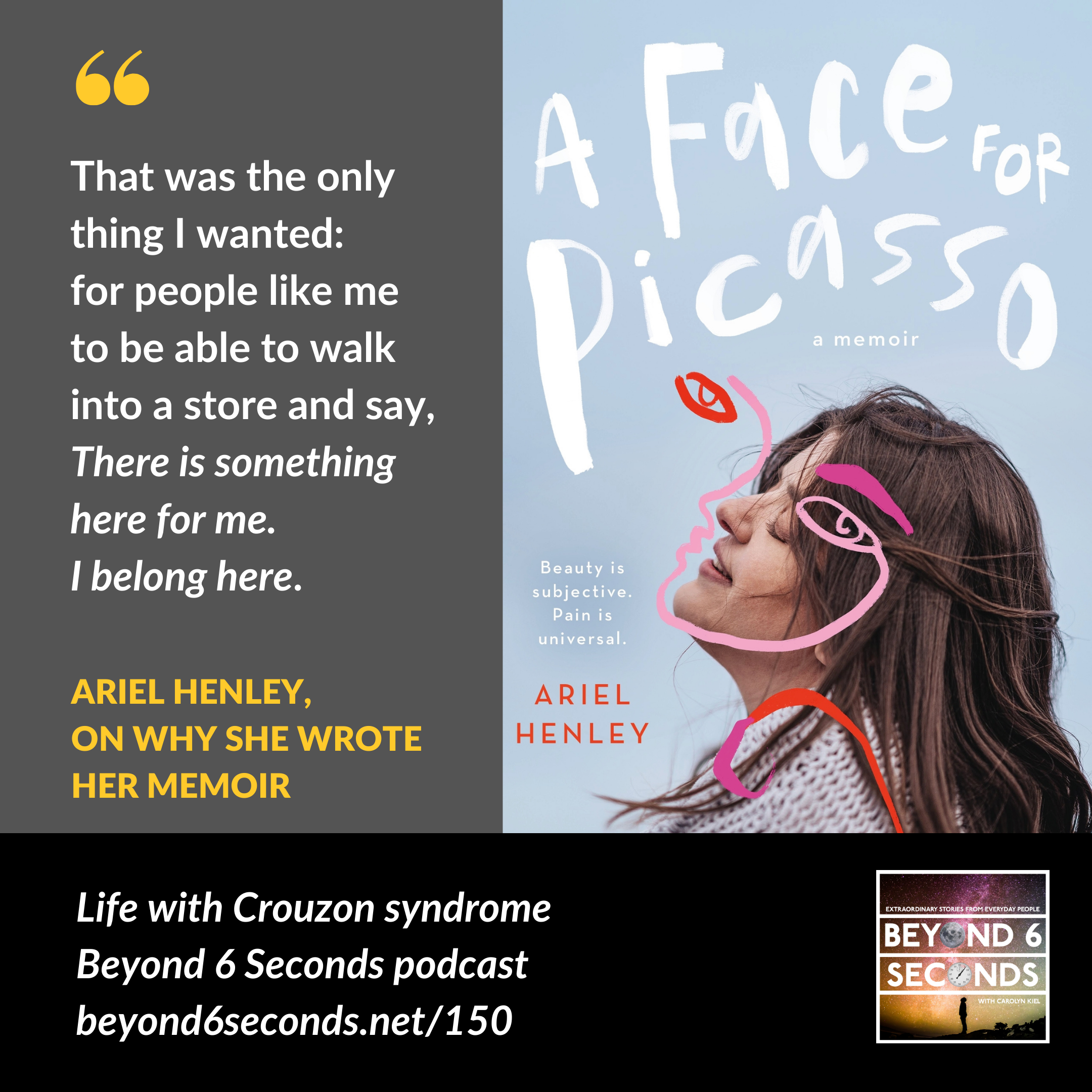

From that day forward, Ariel was determined to tell her story. She transformed that insult into the title of her new memoir, “A Face for Picasso.”

Tune into my latest episode to hear Ariel talk about her book, as well as:

- Her story of growing up with Crouzon syndrome

- The pain and harassment she faced

- Finding self-acceptance

- Her advocacy for face equality and authentic media representation of people with facial differences and other disabilities.

To find out more about Ariel and her work, visit her website at www.arielhenley.com and order her memoir, “A Face for Picasso.”

This episode also features a promo of the Art Heals All Wounds podcast.

Full bio: Ariel Henley is a writer from Northern California with a B.A. in English and Political Science from the University of Vermont and a Master’s in Education from University of the Pacific. She is passionate about writing as a form of activism, and hopes to use her story to promote mainstream inclusion for individuals with physical differences. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Washington Post, and Narratively. Ariel is also the author of A Face for Picasso, a memoir about growing up with Crouzon syndrome.

Subscribe to the FREE Beyond 6 Seconds newsletter for early access to my latest podcast episodes!

*Disclaimer: The views, guidance, opinions, and thoughts expressed in Beyond 6 Seconds episodes are solely mine and/or those of my guests, and do not necessarily represent those of my employer or other organizations.*

The episode transcript is below.

Carolyn Kiel: [Art Heals All Wounds podcast promo] Before we get started with today’s episode, I wanted to tell you about another great podcast I’m enjoying. It’s called Art Heals All Wounds. It’s a podcast where you’ll meet artists who are transforming people’s lives with their work. Their stories will inspire you to live your best creative life, find empathy for others and feel compassion for yourself — as you hear from artists who experience many of the same challenges that we all grapple with.

The podcast’s host Pam Uzzell dives deep into the lives of these artists, bringing out their trials and tribulations as well as the healing joy and wonder that comes with creating artwork.

As an artist, filmmaker & storyteller herself, Pam has a natural talent for leading honest conversations that showcase the healing power of art.

Her interviews with a wide range of creative people —filmmakers, artists, musicians, and performers—all feel like kitchen table conversations sparked by genuine curiosity and a shared understanding of the challenges and rewards of making art and telling stories.

Stay tuned to the end of this episode to hear the trailer for Art Heals All Wounds and find out where you can listen to this podcast.

Carolyn Kiel: [Introduction] Welcome to Beyond 6 Seconds, the podcast that goes beyond the 6 second first impression to share the extraordinary stories of everyday people. I’m your host, Carolyn Kiel.

Carolyn Kiel: Hello! It’s great to have you here listening to the show today. This podcast usually focuses on stories from neurodivergent people – but today’s episode is a little different. My guest, Ariel Henley, is not neurodivergent – instead she is a writer and an advocate for people with physical differences.

She shares her story about growing up with a facial difference called Crouzon syndrome, and how she dealt with so many of the physical, mental, emotional, and social challenges she experienced. These experiences led her to write her memoir, to help elevate the importance of inclusion and representation of people with differences.

She also introduces me to the concept of “face equality” and talks about how the entertainment media influences stereotypes about physical beauty and cosmetic differences as indicators of moral character. I’ve realized that the assumptions we make are so deeply ingrained that we’re often not aware of them, we may even deny them if asked about it directly, but like many other biases in society, we need to identify and challenge them so that we can include, learn from, support and build meaningful relationships with people who are different from us.

This podcast is all about breaking down stereotypes and biases about difference – mainly about neurodiversity, but also about disability, physical differences, and other differences too. If you like stories like these, please remember to follow Beyond 6 Seconds on your favorite podcast app or on YouTube. You can also find more stories like this and sign up for my free newsletter at beyond6seconds.net. This podcast is a passion and labor of love for me, and I really appreciate everyone who listens!

And now, here’s my interview with Ariel.

I’m very excited to have my guest on the show, Ariel Henley. Ariel is a writer from Northern California with a BA in English and Political Science from the University of Vermont and a Master’s in Education from University of the Pacific. She is passionate about writing as a form of activism and hopes to use her story to promote mainstream inclusion for individuals with physical differences. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Washington Post and Narratively. Ariel is also the author of A Face for Picasso, a memoir about growing up with Crouzon syndrome.

Ariel, welcome to the podcast.

Ariel Henley: Hi, thank you so much for having me.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. Happy to have you here. So yeah, I’d love to learn more about what it was like growing up with a facial difference and specifically with Crouzon syndrome. So maybe talk a little bit about like what Crouzon syndrome is, in case people aren’t familiar, and what it was like.

Ariel Henley: Yeah, absolutely. So Crouzon syndrome is a craniofacial condition where the bones in the head fuse prematurely. So when a baby’s born, right, it’s like a kid gets older, their skulls grow, their faces grow, people get bigger. But with Crouzon syndrome, the sutures are fused.

And so. I’m a twin. I’m an identical twin and we both have Crouzon syndrome. So my twin sister Zan and I started having surgery for it when we were eight months old. And so surgeons would literally have to go in and like break apart our skulls and make them bigger for us. Since our heads and faces did not grow on our own, they had to make it bigger so that our brains had room to grow.

And so, you know, as they make the skull bigger, things kind of shift and move around, so then they’d have to go back in and move the eyes and move the nose, fix the jaws. So by the time we graduated from high school, we each had about 60 surgical procedures.

So saying that you would probably assume that my childhood was I dunno, super unconventional. And in some ways it was, but in a lot of ways, it was just like every other kid. We would have our surgeries and then we’d go back to school. We were in public school from kindergarten, for most of it anyway. When we got to high school, we did a little bit of like home teaching cause we were on medical leave. And so we’d have a teacher come to our house for like an hour every week or something like that. And then we mostly just did like independent study. But, we played sports. We had friends.

It was hard in a lot of ways to understand what it meant to have a facial difference and a face that other people felt was wrong and bad. Within our, you know, circle, the people that we went to school with and our friends and our family, they were all used to us. So it wasn’t really an issue. And so I would kind of forget that I had Crouzon syndrome and that I had a facial difference, but as soon as we met people that were not used to us, it was a reminder. Like we couldn’t go to the grocery store without being stared at, we couldn’t go out to dinner with our friends or family, without people having, you know, an issue with us and making comments, like “Look at their eyes, look at their face, look at that girl.”

And so my whole life has been being stared at and being made fun of and harassed. And I don’t even like to use the word bullying because it it’s more than that. It’s more than just being targeted. It’s everyone. It’s children. It’s adults. It’s teenagers. Who would just pick apart everything about us. And so we would go to school. When we’d have surgery, we would leave, have surgery, recover for a little bit and then go back, usually before we were even healed all the way, because we couldn’t miss too much school.

And so we didn’t really talk about things with peers much. We just kind of pretended that it wasn’t a thing. And so we compartmentalized a lot of our experiences. But, yeah, I don’t know. I don’t know if that’s helpful, but.

Carolyn Kiel: It definitely is. And there’s so many threads of conversation I want to follow from here.

So yeah, I mean, just starting from the beginning, when you were describing the types of surgeries where the literally surgeons are like physically like breaking apart your bones and then you’re, you’re like healing, your, you and your sister are healing, and then like going back to school. I’d imagine that’s gotta be like, really, it’s gonna be pretty painful, like almost every time that it happens. So how did you manage through that?

Ariel Henley: There was a lot of dissociating, honestly, and I think to be completely honest, it was painful, but it wasn’t the worst part. Like it was definitely the more of the emotional aspect was a lot harder than the physical, because there were times when we would wake up from surgery and we would look completely different.

Carolyn Kiel: Wow.

Ariel Henley: And not only that, but we are identical twins and we used to be so identical that if you show me a picture of the two of us together at like age three, I have no idea which one is me. Like that is how much we looked alike. And so to not only wake up from surgery with a face that I didn’t recognize for myself, but to then not recognize my sister was beyond my ability to process and no one else around me really understood it either.

So it was kind of like, everything’s fine, everything’s fine. It was a lot of not dealing with things. And so the surgeries were physically painful, but there was definitely the psychological and the emotional aspect that was harder. Because in addition, it was, you know, if I went in for surgery first, my sister would, you know, say goodbye and knowing that I’m going in. And vice versa, if she went in first, it was, you know, knowing something could go wrong and having that realization, even as a child. Not having the privilege of being careless and carefree, it was like death kind of always hanging there.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. You always knew it was, it was a serious event and that there was risk involved. So you and your sister were aware of that.

Ariel Henley: Absolutely. Absolutely.

Carolyn Kiel: Wow. Because you had this sort of unique situation where you have a twin, your twin sister, who’s going through the same surgeries, the same types of treatments.

And I assume very similar experiences as you have. So did the two of you ever kind of talk about or commiserate in any way, or was it literally just like, we’re not talking about this.

Ariel Henley: We would talk about things sometimes, but I think in some ways the beauty of it was that we didn’t have to .Like, we could just sort of grieve together, because that’s really what it was, grieving. It was like a loss of identity of innocence of trying to process these experiences. Yeah, so a lot of times we would just sort of sit together or sometimes even like cry together. Say things like, I’m so tired of this, or like, I don’t understand why it has to be this way. Things like that, but we didn’t really need to go into more details because we could just understand what the other one was feeling and thinking. So in a lot of ways it was, you know, great and a privilege to have someone to go through it with. But in a lot of other ways, I think it was even more traumatizing because there was that added layer of helplessness and fear. You know, it wasn’t just about me. It was about both of us and not being able to control what was happening to me, but also what was happening to my sister and having to see her in physical pain was devastating.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. Yeah. And at what age did you complete your surgeries? When did that stop?

Ariel Henley: We had our last surgery when we were 19, just before we turned 20.

Carolyn Kiel: Okay. Wow. Wow. So yeah, that’s really marked your whole, your whole childhood and growing up is having this reality and the experience really being part of yours and your sister’s lives. Wow.

Ariel Henley: Yeah. And it was really, you know, going to college and I came home my sophomore year and I had surgery during the winter break. And it was, it was a pretty minor surgery, but we were supposed to do it like two more times and it was something I wanted. And after that surgery I was like, No, it doesn’t feel worth it to me.

Like I had spent the first part of college kind of coming into myself a little bit and feeling more comfortable with who I was. And I was like, I don’t wanna keep putting myself through this if it’s not something that’s like medically necessary.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. Yeah. And what was that experience like going to college? Because that’s really the, I would imagine one of the first times that you’re going to a completely new area where everyone’s new, as opposed to like, sort of having your family and the people who know you versus like people who are strangers, like everyone’s new. What was that like?

Ariel Henley: It was very liberating for me. And so I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area and I went to college in Vermont, so about 3000 miles away. And I went 3000 miles away for a reason. And because I wanted to start over, I wanted to be able to drive down the road and not be like, oh, that’s a reminder where I had surgery. And it was like going through the Caldecott tunnel. Like I’m 31 now, or almost 31. I’m aging myself a little bit. I’ll be 31 in a couple months. But even now, like driving through the Caldecott tunnel, like going into Oakland, it triggers me a little bit. It reminds me of being a kid and having surgery.

And so in going to college. I wanted to go somewhere where people didn’t know me, where I didn’t know anyone, where they didn’t see my face at all the different stages. They didn’t see me back at school with stitches and a black eye and swollen and bruised and uncomfortable. I could just be the version of myself that I wanted to be.

And the funny thing about that line of thinking though, is that no matter where you go, you take yourself with you. And so in a lot of ways, it was great for me because while it definitely didn’t fix everything, it gave me the space to process what I had been through. And the space to do away from my family members and my sister. I didn’t have to comfort anybody. I could focus on me and my feelings and really process that myself. So it was hard, but I made a ton of friends. And it was an amazing experience.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. Well, that’s great. Wow. So yeah, I mean, it’s good that people were, it sounds like relatively accepting on the college campus and such or, or with that the experience that you had?

Ariel Henley: You know? Yes and no. Some people were, I think it was like anywhere.

So I grew up in the east bay and, you know, in a very beauty obsessed area. And so it wasn’t that level, there wasn’t this pressure to get plastic surgery if you don’t look a certain way. That wasn’t present. But it certainly wasn’t the case where I could walk down the street and not get stared at. I still got stared at, I still had people make comments about me.

But I think what was different was that I wasn’t as open to criticism. I didn’t care. That’s your problem. And so I really had this mindset of, I’m not going to let other people’s opinions and actions impact how I feel about me. I’m okay with me, great. Now of course easier said than done sometimes, but for the most part, that was what really changed for me.

Carolyn Kiel: And that’s powerful because sometimes that’s a really tough place to get to in your life, you know, no matter what your experience is in life. So that’s, it’s a good place to be once you get there. So that’s good. That’s really good. So, wow. So you went on, you, you graduated college, you went out to get a master’s and you know, you work full time. And now very recently you just released your memoir, A Face For Picasso. So I guess, going back, what inspired you to want to write a memoir about your experience?

Ariel Henley: Yeah. So when I was 12 years old, the summer before seventh grade, my twin sister Zan and I had two operations that really changed what we looked like again. And it was hard because it was middle school and middle school’s not exactly great for a lot of people, whether you have a facial difference or not. But it was a summer of really traumatic surgeries and recovery. And then trying to go back to school and get back to normal felt impossible. For me, it kind of marked this before and after period. It was like, I was no longer the same person anymore. It changed me physically, mentally, emotionally, psychologically in every way imaginable. I was different and I was angry about it. That is how I processed everything that I had been through, which I was pissed off at everyone.

And people, even teachers, principals, vice-principals, students were awful to me. Absolutely awful. Very discriminatory. There were a lot of like microaggressions even, and some were just straight up aggressions. It was very problematic and hard to deal with.

And I remember being in seventh grade and one of the assignments that my teacher gave us was to write a short story. And it could be about anything, but just fiction, short story. Okay. So. I was having a hard time because no matter what I wrote, it always came down to me wanting to write my story. And it was like I was going through so much and I had no idea how to deal with it or navigate it. And so I wrote about it. And so the story I wrote, wasn’t my story necessarily, but it was my story in disguise. I got really great feedback from the teacher and he, he gave me an A and said, you might have a future as a short story writer.

And I was so desperate for some kind of meaning in my life that I really took that, and I ran with it. And I said, one day, I’m going to write my story. I am going to tell my story. I had no idea memoirs were a thing at the time. So I was like, maybe it will be fiction, pretend fiction, you know and I’ll just say it’s a fake story, but it will really be mine. And then as I got older, I began to document everything that I experienced and was going through. And I kept journals, knowing that one day I wanted to tell my story.

But to kind of back up a little bit. When my twin sister and I were kids, we were interviewed by the French edition of Mary Claire, and in the article, our faces were compared to a Picasso painting. So think cubism, eyes over here, nose over here, mouth over here. And I remember at the time cause I was, I was in elementary school, and I remember at the time thinking how special I felt to be interviewed by these fancy journalists. And they took pictures and they interviewed us and we got dressed up and it was, it was exciting.

And I never read the article until after that summer of operations in seventh grade. And so I happened to find the article after going through all this stuff and I was in a dark place and I was just cleaning out the attic and I found it. And so I started kind of translating it. And I saw that comparison and it just fueled my anger even more. And that’s really what drove me to, to write about it, was just trying to make sense of things and also find a deeper meaning within, you know, myself and everything I’ve been through.

Carolyn Kiel: Oh, that just sounds so devastating to find, to find out that way. And I guess, is that where the title of your book comes from?

Ariel Henley: Yeah. Yeah. And so it really, A Face For Picasso unpacks growing up with a facial difference and my relationship with my twin sister and my family, and also the way society treats women and looks at beauty and the emphasis that it places on physical beauty. It really looks at all of those things and unpacks it through the lens of this comparison to Picasso.

Carolyn Kiel: Wow. And yeah, one of the things that you talk about is face equality, which actually was something that I hadn’t heard of until I, until I started reading more about your story. So I’d love to learn more about what that is and how that ties into your book and your story.

Ariel Henley: Yeah. So face equality is basically just the idea that people should be treated equally and have equal opportunities regardless of what they look like. So that includes disfigurements or facial differences, burns, scars, anything outside of the “norm”, really. People who meet these arbitrary standards of beauty, which are, you know, Western standards of beauty, I should say, which are ageist, sexist, classist, racist, all of these things, make more money, they’re treated better. There’s this idea that our physical appearance is somehow representative of who we are. So if you talk about things like identity, what’s the first thing we think of? The appearance of someone’s face.

And so, and this goes back forever, really, that we can judge a person by what they look like. And there are entire like pseudoscience beliefs that the face is indicative of someone’s moral character. And just someone’s going to be more trustworthy if they look a certain way. And they’re going to be smarter if their head is shaped a certain way. And so face equality really examines kind of the role that some of those beliefs play. Because if you, again, if you talk to people about this, people will be like, “I don’t think that. Like, that’s, that’s wild. What?” But it’s so deeply ingrained that a lot of people don’t even realize how harmful a lot of these stereotypes are and how ingrained they are into our practices.

Like look at villains in movies. Freddy Krueger, scarring, facial differences. That is how we know it’s the bad guy. Scar in the Lion King, which is for children, is a bad guy. And he’s literally named Scar. Like that is, you know he’s bad. And so face equality, again, just kind of tackles all of those things and says it shouldn’t matter what we look like. It shouldn’t matter if we meet or don’t meet these arbitrary standards of beauty. We are all people. We all deserve to be treated as such.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And that’s really powerful. And you, you mentioned that you talk about that a lot in the book is sort of these problematic depictions of facial differences in the media which is again, something that, you know, you grow up with that, and it’s almost like you don’t even think about it. It’s just, oh, this is just how it’s depicted in the media. But if you really stopped to think about it, it’s like, you know, they’re taking like that physical, like appearance shortcut to indicate something about someone’s character and that just isn’t right.

Ariel Henley: Absolutely. And it’s, it’s hard to grow up with that. Especially as someone who could not go into a bookstore or go anywhere again, where I saw someone like myself. There was no, I dunno, there was no representation for someone with Crouzon syndrome growing up. And so when I saw characters like Scar or, you know, any villain who looked different, there was this kind of internalized belief that I deserved to be stared at when I was in public and I deserved to be harassed and to be made fun out because I was different. And that’s the price that you pay when you are different. There’s something wrong with me. I am wrong. And so those depictions really just reinforced that line of thinking. And it’s very damaging to a child, especially when there are no other narratives to counter that.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. Yeah, absolutely. It influences anyone who has a facial difference or just doesn’t live up to the standards of beauty that we have in Western society at all. And then, yeah. And it influences everybody else who just sort of has that in their subconscious mind. And yeah, it kind of fuels that sort of staring at and strangeness about differences. So yeah, that is a big one there. Wow.

So your memoir, is it sort of like interspersed with some of your and your sister’s stories growing up with sort of talking about some of these bigger issues around representation and face equality?

Ariel Henley: In some ways. I tried to really take readers inside of my experiences and walking through, you know, going into kindergarten even, and my sister would apologize to our teacher for being ugly and apologize to our classmates for them having to look at her, basically. So things like that. And then, you know, being made fun of at the school Halloween parade where it’s like, everyone’s supposed to be able to dress up and it’s like, no, our appearance isn’t okay even on Halloween when people are wearing masks. And, and kind of walking through, you know, into middle school and talking about the operations we had. Joining the cheerleading team. The ableism that we experienced in school, but without, you know, calling it out specifically. Because I really wanted readers to feel like they were experiencing it and not just tell them “it’s bad to treat people like this because,” but to make them feel it. I really wanted people to have a deep understanding of what it means to be different. It isn’t just, oh, I don’t like the way that I look. It’s like no, Crouzon syndrome isn’t the problem. It’s the way I’m treated by society that’s the problem. And so unpacking that ableism in that way. And so it’s more literary in that sense.

It is an intense book. You know, I’ve had an intense life. Like I will, I will totally own that. But I did try to write it in a way, and this is partially why I was really drawn to it technically being a young adult memoir, although it’s targeted toward teenagers and adults alike. But I wanted readers to be able to read it and not feel like they were getting second hand trauma from reading it. I didn’t want it to be so heavy that it was like, “oh, my gosh, I’m just overwhelmed now. Like, I have to process this.” So it’s kind of a balance between showing and telling in that way. So my, my answer to your question is yes, a lot of those issues are incorporated, but it’s not as direct as you might expect.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, I think that’s, that sounds like it’s a good balance because it is hard to, to share an experience like that with, as you said, it being like really heavy and kind of getting that second hand trauma or, or impact, but at the same time, not being lecture-y. Because I guess a, you know, sometimes people get really defensive for some reason when they’re called out on things that, their biases that they may not realize that they have. So it sounds like that yours really balances out with the story.

Ariel Henley: I tried to be very honest in my story, and that includes honest about myself and my own responses to things. It’s definitely not a story where you’re gonna read it and think, “wow, Ariel thinks she’s this like little angel and everything bad has happened to her.” Like, I was mean. I did not handle things well. Like I would get mean at times. That was my trauma response. And so having to unpack some of that anger as well.

And a lot of what the book does is look at how, again, how ingrained beauty standards are and in this, in comparing it to a Picasso painting or comparing it to Picasso, I should say. I talk about Picasso, and his life, and his really problematic views on women and how abusive he was. And because especially being compared to a Picasso painting, I had this idea that to be compared to a Picasso painting, because I did not understand the idea of separating the art and the artist. Like, to me, I was like, that’s not a thing. Like everywhere I go, I am my face. Like you can’t just decide what version of yourself people see. Like, everything I did was an extension of me and what I looked like. And so to compare me to a Picasso painting really felt like I was being compared to Picasso.

And so, especially as I was growing up and I was dealing with the trauma of everything and I was really struggling with how angry I was about all of it, I felt like a Picasso. I started to internalize this idea that I was abusive and I was cruel the way that Picasso was. And because he was very abusive towards women. And instead, you know, I wasn’t realizing that I was like, actually, I was actually one of I guess in this comparison, one of Picasso’s mistresses or wives, because they were so abused and I was abused by the world around me.

And so did I always handle things well? No, but it helped me to understand that there’s a difference between anger and rage and it’s okay to be angry. When you’re being abused, it’s okay to be angry. You know, it’s up to you to like work through that trauma and figure out a healthy way to express that and deal with that.

Absolutely. But yeah, that comparison just really helped me to understand my own journey and kind of forgive myself and the people around me. And also talk about again, how deeply ingrained beauty standards are in our society.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. Wow.

Ariel Henley: That was a lot, I’m sorry.

Carolyn Kiel: Well, that’s powerful. Cause I didn’t really know much about Picasso’s personal life or what he was as a person. So to, to know that and understand how that impacted you and how that wound into the story like yeah. Wow.

You mentioned earlier that you and your sister and your family didn’t really talk about your Crouzon syndrome that much growing up. So now having this forum, or just sort of making this decision to really come out and share your story, I’d imagine that that is, you know, somehow at least cathartic or therapeutic or, or helping. It just seems like a turning point in some way.

Ariel Henley: Yeah. My family has been incredibly supportive. I have a lot of writer friends who do not have supportive families when it comes to telling stories. You know, and I admit this, it isn’t just my story. It’s my sister’s story. My family story. It’s their story through my lens, you know?

And that’s the cool thing about memoir. If they were going to write their own, it wouldn’t be the same as mine. It’s going to be different because that’s how memory and life and experiences work, which is great. But you know, my, my family has known that I’ve wanted to write this book since I was 12 years old. And so even growing up my parents would be like, oh, it’s another story for the book, whenever I didn’t feel like doing something. And so it was my way of showing up for life and their way of really encouraging me to go do things. It was like, You know, worst thing, worst thing that could happen is, just one more thing to write about, Ariel. And so if I wasn’t writing regularly, my dad was like, you said you want to be a writer. Writers have to write. Like, come on, get to it. You know, very loving and very supportive. And it led to a lot of really great conversations with them. And a lot of healing I think has happened.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. Yeah, definitely. And that’s great that they were supportive and they encourage you to write constantly. Because yeah, I mean, as you said, writers have to write. So preparation for that. Very cool.

So, yeah, so I know your book literally just came out, we’re talking in early December, and it came out like last month. So it’s very, very new. What kind of goals do you have for either your writing or just your advocacy around, you know, face equality and challenging beauty standards?

Ariel Henley: Yeah, I you know, I had someone on Facebook tag me in a photo of their daughter who also has a craniofacial condition who looks a lot like I did when I was a kid, holding my book in Barnes and Noble. And I started crying. I immediately started crying. And to me that, that’s what I wanted. That was the only thing I wanted was for people like me to be able to walk into a store and say, “there is something here for me. I belong here.”

My goal really is to get my story in as many hands as possible, especially into the hands of people who grew up similarly to me. So kids with craniofacial conditions. It is my dream to have my book read in schools. You know, I mean, as every writer I’m sure would say. But not, again, it’s not about me, not about my book, but to start that conversation early and so that people really start to understand the impact of discrimination against people with disabilities and facial differences.

And so that people can, you know, walk down the street and go out to dinner and go grocery shopping without being stared at and harassed and made fun of. Like, it’s exhausting. So my goal really is to just keep, keep doing what I’m doing and hopefully more and more people will listen and care. I am going to work on, well I am working on additional books. Fiction this time. But I want to keep writing about characters with facial differences to kind of help normalize that, but not have it be like a key aspect of their identity. Like she has brown hair and Crouzon syndrome and brown eyes, you know, just to help normalize it.

Carolyn Kiel: And that’s powerful, you know, one as a, an educational tool for people so that, again, people aren’t, you know, it’s not something that gets stared at that people are just not exposed to, but also really that representation. So it’s like, like you’re providing that representation that you didn’t really have growing up. And now other kids with Crouzon syndrome or, or other facial differences, can see that as a great example.

Ariel Henley: Yeah, exactly. And I’ve had some doctors and even a couple of mental health professionals reach out as well to talk about how my book has helped them better understand the trauma around these experiences. And so that’s been really incredible as well to kind of shift some of the conversation there. So that when patients do go in for surgery or do have one of these conditions, it’s not just about, “okay, let’s expand the skull.” It’s “okay, well let’s get these kids in therapy and let’s get talking about this and help them actually work through this and process it.” So that’s been really amazing.

Carolyn Kiel: Oh, wow. That’s great. Yeah. Just hearing directly from people who have gone through it and it will definitely help them, you know, the next generation of kids and even adults who, who have to face these issues. Wow. Oh, that’s so cool. Wow.

Well, Ariel, thanks so much for being on my show. How can people get in touch with you if they want to learn more about your book or buy your book?

Ariel Henley: Yeah. Well, first off, thank you so much for having me. I really appreciate the opportunity to chat with you and share a little bit about my story. I have a website, ArielHenley.com. People can find me there. You can send me an email at Ariel at ArielHenley.com. Or if you Google A Face For Picasso or go to any bookstore you should be able to find my story.

Carolyn Kiel: Very cool. And I’ll put your website link in the show notes so people can find it there. And yeah, as we close out, is there anything else that you’d like our listeners to know or anything that they can help or support you with?

Ariel Henley: Just read diverse stories, celebrate diverse appearances. I think just talking about these issues is a great start. And so I appreciate any listener that has taken the time to, to hear my story and think about what face equality and facial difference means so, thank you.

Carolyn Kiel: Wonderful. Thank you, Ariel, for sharing your story and for educating me and all of us more about face equality and just, you know, really thinking about the impact of beauty standards and providing that representation. So, yeah. Thank you so much.

Ariel Henley: Thank you.

Carolyn Kiel: Thanks for listening to Beyond 6 Seconds. Please help us spread the word about this podcast. Share it with a friend. Give us a shoutout on your social media or write a review on Apple Podcasts or your favorite podcast player. You can find all of our episodes on our website and sign up for our free newsletter at www.beyond6seconds.net. Until next time.

Carolyn Kiel: And now, here’s the trailer for Art Heals All Wounds.

[Art Heals All Wounds trailer]

Speaker 1: I don’t know if I even realized what the term artist meant when I first started making things.

Pam Uzzell (Host): Welcome to Art Heals All Wounds, the podcast where we meet artists transforming lives with their work.

Speaker 2: And this opera company in Orange County, Southern California, wanted to do a project that focused on the Latino cultural experience. That sort of began my trajectory into writing opera.

Speaker 3: To see this representation that reflected back a part of the history that actually included my, my people that made me feel seen in this powerful way.

Speaker 4: Very often a poem begins in absence for me, because then it opens up a realm of imagined possibility.

Pam Uzzell (Host): We hear their stories of how their work grapples with all of the issues that we all grapple with.

Speaker 5: She wanted the best for me. I mean, being a single mom, I remember she gave me a Fisher-Price camera. I would carry it everywhere.

Speaker 6: People being evicted left and right. And I remember walking down the streets and just saying, oh my God, this is not my city anymore. And then the melody came, and a whole song came, and it came so quickly.

Speaker 7: As I became an adult, I started getting terms like feminist terms and political terms and ways of understanding what it means to be different. And I started wanting to change the field of media.

Speaker 8: And I started to make friends with people that didn’t have disabilities. And I used to try and act as much as I could like them because I wanted to be what you would call normal.

Pam Uzzell (Host): Through stories, we gain empathy for others and we find compassion for ourselves.

Speaker 9: So the stories that you tell yourself are the story of that you’re making of your life, it’s not the truth of who you are. It’s the story that you’re living.

Speaker 10: When it comes to stories around disability, that there’s joy, there’s sex, there’s humor.

Pam Uzzell (Host): This podcast is an invitation to find inspiration together.

Speaker 11: I say I’m a personal accountability partner. You tell me what you want to do, and let’s find a way to get it done.

Speaker 12: Creativity is a human right. We’re all born being artists.

Speaker 13: I’m a human being first and foremost. And then I am a creator.

Pam Uzzell (Host): Listening to the stories of these artists helps us to live our best creative lives.

Speaker 14: If you can keep your joy, no matter what brings you joy, there are just so many modalities of art. There’s no way you can’t be a better person.

Pam Uzzell (Host): You can find us anywhere you listen to podcasts or at our website, ArtHealsAllWoundsPodcast.com.