Nadine Drummond is an award-winning journalist and filmmaker from London with roots in Jamaica. A former producer and reporter at CNN and Al Jazeera, she now develops media and content strategy for 14 African countries in her role at the United Nations.

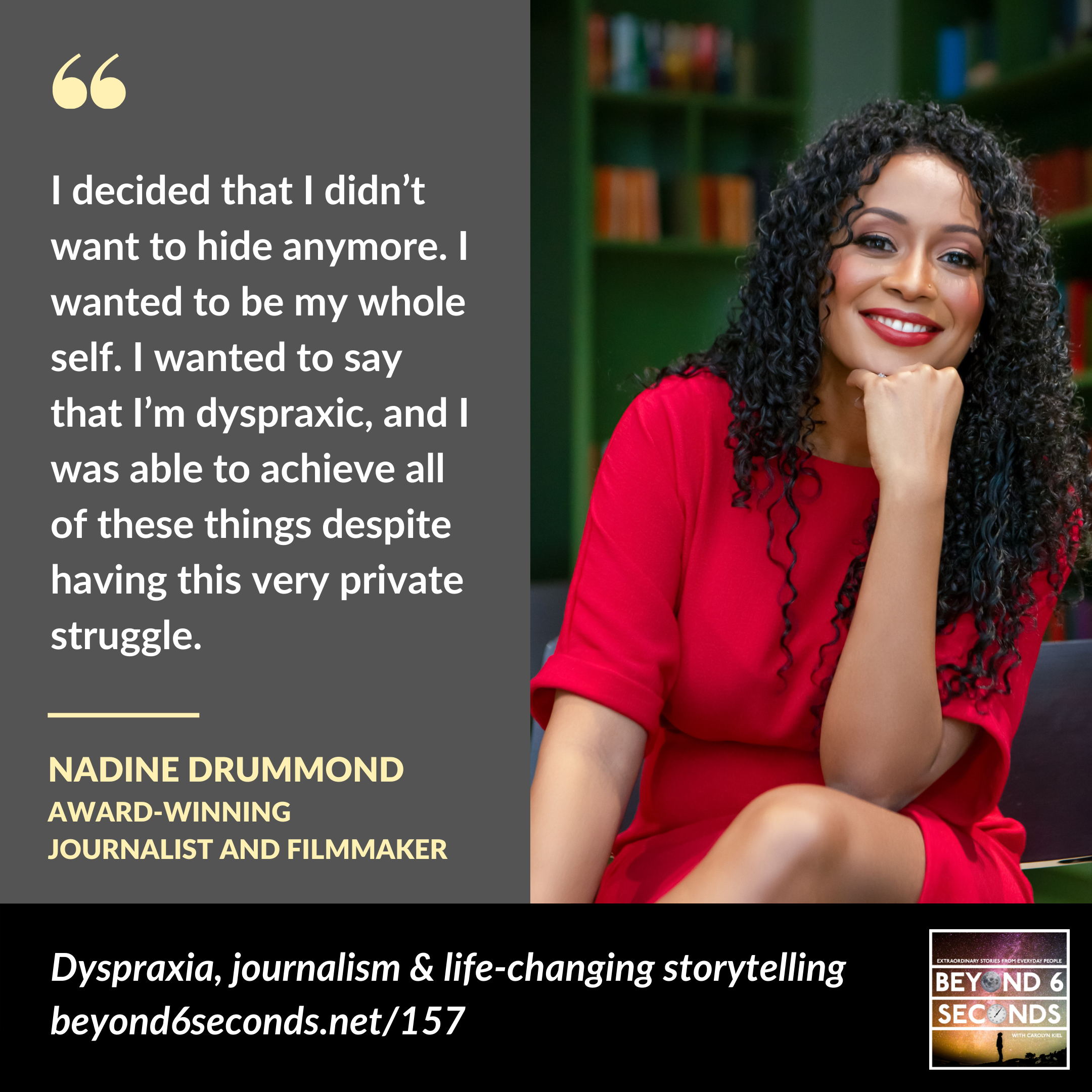

Nadine is also dyspraxic. After her dyspraxia was finally diagnosed in college, she denied it and hid it for years. Eventually she came to accept it — and when she wrote about it publicly for the first time on LinkedIn, her post went viral.

As a journalist and filmmaker, Nadine credits much of her professional success to her dyspraxic thinking strengths, which enable her to creatively visualize, conceptualize and tell compelling stories that move people to take action. Her work has raised millions of dollars, changed government policies, and improved the lives of thousands of people around the world.

On this episode, Nadine talks about her life as a dyspraxic child, student, journalist and filmmaker. Her experience is a testament to how working in your strengths can empower you to make a difference.

Learn more about Nadine at the links below:

- “This Little Girl is me” – Nadine’s viral LinkedIn post

- Nadine’s Medium blog

- Nadine’s journalism projects

(Content warning: Starting around minute 50 of this episode, Nadine talks about gender based violence and sexual assault in Central African Republic. This is the topic of her documentary film that helped extend the life of The Water Project, which directly protected and improved the lives of women in that country.)

Subscribe to the FREE Beyond 6 Seconds newsletter for early access to my latest podcast episodes!

*Disclaimer: The views, guidance, opinions, and thoughts expressed in Beyond 6 Seconds episodes are solely mine and/or those of my guests, and do not necessarily represent those of my employer or other organizations.*

The episode transcript is below.

Carolyn Kiel: Welcome to Beyond 6 Seconds, the podcast that goes beyond the six second first impression to share the extraordinary stories of neurodivergent people. I’m your host, Carolyn Kiel.

I am so excited to bring you my conversation with Nadine Drummond, an award-winning journalist and filmmaker!

We cover two main topics during this episode.

The first half of our conversation focuses mainly on Nadine’s experience with dyspraxia. We talk about what it was like for Nadine growing up with undiagnosed dyspraxia as a Black girl with Jamaican roots living in the UK, as well as how her dyspraxia diagnosis in young adulthood impacted her life as she denied it at first, then came to accept it and, more recently, talk about it publicly.

In the second half of the episode, Nadine talks about her news career that has taken her all around the world. She shares how journalism lets her leverage her biggest strengths, and how her dyspraxia helps make her a compelling storyteller, writer and filmmaker. Through her work, she brings attention to the issues she cares about the most – women’s rights and girls’ rights — and her work has had a real impact on many people’s lives.

As a heads-up, this half of the episode also has some descriptions of gender based violence when Nadine talks about making her film in the Central African Republic – please use your discretion if that’s a tough topic for you to listen to. That part of the conversation starts around minute 50 of this episode.

If you’re interested in stories about neurodiversity, please check out my other episodes at beyond6seconds.net or by following this podcast on your favorite podcast app. I even have a free newsletter if you want me to email you when I post new episodes – you can sign up on my website.

And now, here’s my conversation with Nadine.

On today’s episode, I’m speaking with Nadine Drummond. Nadine is an award-winning journalist and filmmaker from London with roots in Highgate, St. Mary in Jamaica. She’s the Regional Communications Lead for the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner in Southern Africa, where she’s developing the media and content strategy for 14 African countries.

Nadine has been a producer and reporter at CNN and Al Jazeera. She has a law degree from the University of Cambridge and a master’s degree in communications from the University of Miami. Nadine, welcome to the podcast.

Nadine Drummond: Wow. Thank you for having me! When you read my bio, it’s like, oh, that’s really me, because I don’t think of myself in those kind of literal terms. So thank you. You kind of boosted me. Thank you very much, Carolyn.

Carolyn Kiel: All right, you’re welcome. You’ve had an amazing career. What I just read in your bio is only a small part of all your accomplishments, and I’m so excited to learn more about that, and learn more about you growing up, because one of the main topics that we’re here to talk about today is dyspraxia and your personal experience with it. So maybe tell me a little bit about what dyspraxia is and how you experience it day to day.

Nadine Drummond: So dyspraxia is best described as a learning processing and coordination disorder, and it’s an invisible disability and it can impact every single aspect of your life, depending on which part of the condition you’re afflicted by or suffer from most.

So with my experience of dyspraxia, it’s a learning processing disorder. Yes. I have coordination issues. Like I can’t ride a bike. Yeah, I can’t ride a bike. I’ve tried as a kid. I gave up. As an adult, I tried when I went to Cambridge, it’s a biking town and your lectures and your lecture halls and the different libraries, and when you have to go and see your tutors. I mean, I, I lost so much weight because I spent so much time walking and/ or in taxis to get around. And so I thought, I’ve got to try and ride a bike again. And I failed because I, I couldn’t balance, I couldn’t get my coordination right. Even though I’m quite good at sport, I’ve got good hand eye coordination, but it doesn’t work. I don’t, I’m, I’m an okay dancer, but I’m not like a fantastic dancer. I’m not very good at aerobics or step aerobics because I can’t keep up and follow any kind of intricate routine. So those sorts of things to me have to be very basic. So that’s how the more coordination affects me.

Like I can tell my left from my right. I took my driving test about four times because I would hesitate between left and right. So even when I moved to America to go to school, many times I’d be driving on the wrong side of the road and not even know. But the benefit was, was it that because the roads in America are so big, you can switch over before you have an accident. So it takes me a while to to be able to acclimate, whereas for most people that don’t have dyspraxia, these things are second nature, and they’re not second nature to me. I have to work really hard at them.

But the thing that really affects the way in which I live my life is the processing part of the disability, which means that I don’t always remember things. It’s different from dyslexia because dyslexia affects or can affect your spelling. My spelling’s affected, but not the same way a dyslexic’s is. My vocabulary isn’t affected in the same way. And my ability to read and write comprehension isn’t affected. In fact, that’s my superpower.

But my day-to-day living is extremely organized. So everything has to be in the same place. And everybody in my household has to be trained to put everything where I leave it, because if I put my phone somewhere else absentmindedly, it can take me hours to find it. Car keys, anything, everything has to be in the same place.

And I’d like to explain it like a chest of drawers. So in your brain, you have, your brain’s organized in a particular way. And if we think of our brains like a chest of drawers. And in one part you put your underwear, you put your socks or your tights or your vests. That’s how most people order the information in their brain. For me on great days when I’m not stressed and I’ve had enough sleep, I can put all of my undergarments in the correct drawers. But on most days that doesn’t happen. I’ll put my underwear in my sock drawer, my socks in my vest drawer, my my vest in my like say pantyhose drawer, whatever. And I won’t know that I’ve done that. In my mind, everything is in the correct order, but in reality, it isn’t.

So because I function at such a high level, how that behavior is often perceived is, “oh Nadine you’re careless. Oh Nadine you’re not paying enough attention. Oh Nadine, you just need to focus more on details.” And it’s not that. It’s because I have this disorder or disability that I can’t control that prevents me from always organizing in the correct way.

And so I find, I take copious notes, I write everything down and I seek clarity for everything. Is this what you need? What time is this? How is this going to work? At every single step of the way. So at work, people become an excellent project manager and I’m good at coordination, and I’m good at organizing, I’m good at delivering projects. But that’s my everyday survival, because if I don’t put my keys in the right place, I can’t leave the house.

Carolyn Kiel: Oh, wow.

Nadine Drummond: So I’ve I learned these skills throughout my life from when I was growing up, my dad knew there was something wrong, but he didn’t know what it was. And they said I wasn’t dyslexic because my, my comprehension and my vocabulary was too high. But dyspraxia wasn’t a thing. It didn’t exist then, or if it did, the people that I was being taken to didn’t know what it was. And so I had this thing that I just had to find a way to cope with, but I didn’t know it was a thing because I didn’t know any different because that was how I lived my life.

And I come from a Jamaican family and my parents have traditional understandings of what a disability is, which is physical. And there wasn’t, there was no room for second best. There was no room for failure. If you needed to do something, it needed to be done. And I just had to learn from a very early age, how to get things done, despite this disability that I was laboring under. I had no idea that was what was happening, but I found different strategies of coping, which is what helped me cope later on in life.

And that doesn’t mean that it’s, I’ve just been coping and it’s been great, and I’ve never had any issues, because I’ve had lots of issues at work with different managers, that sort of thing. But I’ve just been able to out strategize often, which is another skill you learn because you can’t do things the same as everybody else. So you have to learn how to work around systems and people and to create new systems for yourself that you often find other people benefit from too, because they’re smarter.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, definitely having that structure in place, especially if you’re working with a lot of different people, I could see how that, that helps a lot.

And probably there, it sounds like there’s probably a lot of trial and error because you’re teaching, you’re really teaching yourself what you need in order to be able to, you know, as, as you’ve said, sort of function or get, get through your day to day life and get things done that you need to get done in life. Yeah.

Nadine Drummond: It has been, and it can be at different times, really challenging. Because you have a secret. Because of most people’s ignorance around disability anyway, particularly learning disabilities, you run the risk of, and it’s a serious risk. And this is a conversation that’s had among many people with neuro diverse, which is a preferred name now, neurodiverse. Is that once, if you’re able to hide, you hide, and you keep it secret. Because once it becomes public, people think it means you’re intellectually incapable, which isn’t what it means. It just means that you have a particular challenge. It doesn’t affect your intellectual ability. It affects the way society determines that your intellectual ism is shown, through exam taking under timed conditions. And most people that are neurodiverse are actually quite creative. And those structures don’t work for people like us.

And so I say to my family now, and all of my friends that are directly from the Caribbean or from Africa, I would never have had the opportunity to succeed in a Caribbean or an African environment. Because despite how clever I am or how bright I am, the structures were very traditional. They’re very colonial: reading, writing, and arithmetic. And if you cannot perform under all of those conditions, all of the time, academically you’re just not going to get through. You’re not going to pass your eleven pass, you’re not going to be the top of your class. You’re not going to get the scholarship. You’re not going to go to the top school. And so being in the west or being in England gave me the opportunity, it gave me a bit more breathing, breathing room, a bit more grace.

And I mean, I did go to a private school, so that obviously afforded a lot more privilege. But because it was so heavily creative and art space, I was able to be good at something. I didn’t have to be good at maths. I still don’t have a maths qualification. Right now, I can’t teach in England because, I can never be a teacher because I don’t have a maths qualification. But I can teach at university level, but I can’t, I could never be a qualified, traditionally qualified teacher because I don’t have a math GCSE. In the Caribbean, I would never qualify for a scholarship because I don’t have a maths qualification. So the system really discriminates against people who are neuro diverse that has tremendous talent in other areas, even academic areas.

I’m good with words, I’m a storyteller. That’s what I do for a living. I produce content. So I wouldn’t have had the ability to be good at something. If I wasn’t good at the traditional reading, writing and arithmetic, I would just feel, I would, I wouldn’t know what it would be like to win, and what it is to be good at something. And when you’re growing up, you need to be good at something. You need to be able to claim something irrespective of what it is. And that’s what I had. I knew what I was good at from an early age. I knew that I was good at writing.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And yeah, as you said, that is important to sort of have, even if it’s just one thing that, you know, that you’re really gifted at, because a lot of times that becomes your area of passion and often turns into a career.

So, it is really amazing how the places where we grow up, whether it’s the countries we’re in, the cultures we’re part of, the societies, because every society views things like disability and neuro-diversity in, in different ways. And I think there are always challenges, no matter where you are and where you’re growing up, but they just look different based on that.

Dyspraxia or developmental coordination disorder, however it’s defined in the standard psychological diagnoses, I’ve heard it’s a relatively recent diagnosis. So I, I guess it’s not a surprise to hear that you weren’t diagnosed with that for awhile. So just how did you wind up finally getting diagnosed?

Nadine Drummond: When, it was when I was at university. So when I was at Cambridge, so the collegiate system there operates very differently from most other universities. So you have your lectures that you go to, but you also have very small tutor groups. So maybe one to four people. And so I used to perform tremendously well. I’m a good public speaker. I’ve got great skills of emotional intelligence. I read really well. I’ve got great comprehension and I’m a good strategist. So law, even though it bored me to tears, but that’s a whole other story, but I was actually very good during my supervision. So my predicted grades during exams, were off the charts, they were incredibly high. But I would fall two or three grades down, like a whole grade. So I might say, being predicted, so like a 3.8 or 4.0 in an exam and I’d get 2.5.

Carolyn Kiel: Wow.

Nadine Drummond: And so one of my teachers said to me, “this is outrageous. I know you very well. I know you work very hard. I see the papers that you turn in. And it doesn’t correlate. I do not understand why you perform so well in class, technically, and then in the exams you do so poorly. It really doesn’t make sense. I’m going to send you for an assessment.” And I said, “but I’m not dyslexic.” She said, “no, there are other things.” She said, “there are other things. There’s something else going on here. And I know it’s not because you’re feckless, it has to be because of something else.” And so it was, she was really good for that at the time.

And so I went to the the education center and I had a test, and it came back and it said that I was, I was dyspraxic. And I’d never heard that term before. And Google wasn’t a thing then. You couldn’t, it wasn’t easy to have access to all of this information. So I went to the library and I pulled a few books and even then it wasn’t broadly written about, so then I had to go to different medical reports and research, and I found this condition that they said that I had, and I became very ashamed. I became self hating, actually. It was more than shame. I realized what was wrong with me because it was an issue. I realized that there was actually something wrong with me. I wasn’t trying hard for no reason for all of these years, but there was actually something that was making it so much harder for me.

And then I did something that actually really hurt me a great deal, which was that I denied it. I said, no, this is not correct. This isn’t right. I don’t care if there’s something wrong with me, I’m just fine as I am. And I’ve just got this far by myself and I’ll be fine. Which actually did me a great disservice, because under English law, I was entitled to lots of different benefits. Extra time on papers. The university would have provided extra tutoring in areas that I was struggling in, or I needed more support in. And more importantly, I would have been given extra time in my exams, which is where I really needed the help.

And I denied myself that. And as a result, I didn’t graduate with this higher class degree as like, as I, as I could have or should have. And I went through the rest of my life up until very recently keeping this thing secret. Of course the university knew I was dyspraxic. So with the career service, I would always be a mentor to other people at my university or my Alma mater with other neurodiverse conditions who wanted to keep it secret and also work through strategies around work. So it was really people that were dyslexic, dyspraxia and had dyscalculia as well, finding ways that they can manage bullying bosses or people that don’t understand their conditions. So I still worked in a very private capacity with people like me.

But publicly in my own life, I was very private. I’d worked out enough strategies to be able to get by. It still inhibited my career in many ways. And I wonder how sometimes different things would have been if I was more honest. on this isn’t even the right word. If I was more open, but part of being open is feeling safe and feeling protected. And in journalism, which is a ruthless profession, you don’t always feel safe or protected in that kind of way. And because it’s so competitive as well, you have to be on all the time and any weakness can and will be used against you. And so I made my decisions, and that’s not to, I’m not blaming journalism. I mean, I became a journalist. I love being a journalist, but it’s the nature of the profession, but I think does need to change, but it’s the nature of the profession. And so it was me finding a way to keep my secret, but still achieve what I needed and wanted to be.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. That decision that we make once you get a diagnosis or once you realize that there is quote unquote, something going on, there is that challenge of, you know, how open do I be about it? And I, I do hear a lot of people certainly at first and sometimes for years, really just trying to bury it for a lot of the reasons that you just mentioned. A lot of times, if you’re not in a space where you feel like you’re going to be supported and safe and where you’re worried about losing the things in your life that are important to you, yeah, it’s, it’s a big challenge. So I mean, it it’s especially brave and courageous to come out and really be open about it and inspire other people especially as someone so visible and in journalism and someone who’s, you know, on camera and, and really part of the public discourse all the time. It’s important because then people get to see role models of people that are like them who are doing great things.

Nadine Drummond: Yeah. I think that COVID or pandemic and the lockdown, much of Europe was locked down for the last 18 months, it forced me to become far more reflective. I think like lots of people, I’m far more honest with myself about the type of life I wanted, the type of person I wanted to be and the type of value I wanted to add. And for a very short period of time, life was no longer finite. It could come to an end. Maybe if I got contracted the wrong strain of this virus, I might not make it.

And then it forced me to really think, well, okay, how do I want the next, however long I have left on this earth. If climate change doesn’t get us first. Like what, what do I want to do? Or, or how, how do I want to be? And I decided that I didn’t want to hide anymore. I wanted to be my whole self. And I wanted to say that I’m dyspraxic and I was able to achieve all of these things despite having this very private struggle. And I know everybody has their private struggle. It doesn’t, I’m not trying to compete in like the suffering Olympics, but everyone has their unique struggle, but this struggle was particularly unique for journalism. And I did really well. I did really well and I am still doing really well.

And it was also for the young people that were not able to go to school, that we’re having to sit exams, that didn’t have the same kind of social support, that perhaps had mental health issues . The impact on young people was really hard. And I didn’t want any of those young people to feel like all of these burdens that they had were their own. All those young people that had other challenges, not just neuro diverse challenges, but other challenges, whether they were economic, social, political, cultural, whatever they were, that there’s somebody else.

And so I came across this campaign on LinkedIn called “this little girl is me” and I thought it was just such an amazing campaign. And it was from a tiny NGO in a country in Southern America. I can’t even remember. So I won’t even try. And it was just for this, this tiny charity that just helps little girls and their self-esteem.

And as you know, girls in most countries, especially under developed countries, aren’t particularly well-educated. And if they’re from very poor backgrounds, which is most of them, then the chances of going to school or even believe that they can be anything other than their environment dictates is is, is is sort of very difficult for them. And they’d also started doing some work in Africa as well. And I said, let me just put my voice there because there has to be somebody within this organization that looks like me.

And it’s, it is powerful when you hear other women speak as a woman. But as a little girl, if I saw somebody that looked like you, and you were speaking inspirationally, it would affect me and impact me. Because I’m going to be a woman too, and then I can be just like you. But if you looked like me or I saw myself in you, that representation is so much deeper. So I decided that I would tell my whole truth to these little girls that will be struggling somewhere in the world. And hopefully it will resonate with them and they would be able to know that it’s possible, whatever their ailment is or whatever their predicament is, or whoever has been mean to them for whatever reason or whether or not people are telling them they’re not smart enough, or they’re not going to make it, or they don’t have the resources and whatever structures, impediments, whatever it is that’s going to hold them back, there’s a light. They can see somebody and say, okay, I remember this one woman that I saw and she had dyspraxia too, or she was brown or she was Black like me too. Or her parents were immigrants too. Or whatever it is they can hang on to something that will just hold them firmly in their desire to, to change their life or to get an education or go to school.

And so that was, it was a culmination of things. And then my post on LinkedIn went viral, which I was not, I never had the viral post on LinkedIn. I’ve had like good numbers, but never viral. And so it really resonated with lots of people, especially parents, people with dyspraxic children. I got lots of messages from women, primarily women who were raising dyspraxic children. And quite a few from other African and Asian women, people of African and Asian descent who were raising children, extremely accomplished professional women. But I could understand the struggle of having a child that’s neurodiverse, who’s expected to be a lawyer or a doctor or an accountant or a NASA astronaut, and your child doesn’t have the ability. How can you support them without making them feel horrible about themselves?

And so that’s what I spent most of my time doing after the post was just saying to parents, “find something your child is good at. It doesn’t matter whether you think it has value or not culturally, you need to protect them so they can be good at that one thing. And once they acknowledge and they’re celebrated for being good at this one thing, it could be two things or three things. Then that level of confidence, it’s almost like it rewires your brain. It changes like the synaptics in your brain, and you’re able to have the courage to do other things.” And so a lot of it is courage, but that courage, that needs to be built somewhere because sure, even in our own lives, we know people that are extremely gifted, extremely talented, but because they didn’t have that injection of supports or self-belief, they don’t always perform at their maximum capacity or full potential, despite how brilliant they are.

So the key, I just think for everything is confidence and courage. People need to be, obviously not bluster, because we don’t do bluster. Right? I mean, sometimes we fake it til we make it, but it’s just literally having this self-belief that okay, I might be this way. I might look like this. I might have this particular challenge, but it’s going to be okay. I’ll find a way, because I know that I can. And that’s really the message that I wanted to share. That it’s been really hard and it’s been really tough, but I survived a pandemic, millions of us survived the pandemic. And we can rebuild, we can restructure, we can, we can redefine and we can improve ourselves. We can improve our communities. And that hopefully would improve our world. And so that was that, that, that, that was it. That was all of it.

Carolyn Kiel: Wow. Yeah. And that’s, that’s powerful. Sharing our stories is so critically important for so many of the reasons that you just mentioned and just to inspire and provide those examples for people who are younger than us, who are, you know, as you said, look like us, or just, we relate, they relate very closely to us from, you know, whether it’s gender or background or ethnicity or race or whatever it may be.

Even just someone having one person to look up to and see as an example, and even provide some support, even if they don’t know that person, just that inspiration. It’s just a, you know, it really can set people on paths that unlock their brilliance in ways that they may not be inspired to do otherwise.

So, yeah, that is really, really powerful. And yeah, actually that post from the campaign, this little girl is me, is how I found out about you, your viral post. And yeah, I’ll put a link to it in the show notes because I still have the link for that. So that’s a great one for people to read. Yeah, it, it’s amazing how the power of that story.

And, and you talk about a lot of really challenging things from your childhood there. In addition to having an undiagnosed learning disability, you talk about in school facing racism and unfair treatment from teachers and all kinds of things that that go on top of, of dealing with a learning disability. So it’s it’s very real and, and really inspiring for people, for people who are going through that or, or know people who are facing those challenges.

Nadine Drummond: It, it, I mean, school was horrible. I’ll let everybody read the posts, but I never really liked school. I’ve never liked school. I’ve liked learning. I’ve never liked school. And I think there’s a difference. And I think if a young person says I hate school, that doesn’t mean they hate learning. I could never tell my parents I hated school. That was unacceptable. But always liked learning. And that’s been a lifelong thing for me, but I don’t always think schools are the most appropriate place for learning for everybody. And neither did my parents because we were homeschooled. We were taken out of school and homeschooled so that we can pass, we could pass the exams we needed to go to the private school system, which had its own other set of challenges, which I won’t bore you with here.

But I just think that in terms of learning, the way in which we think about learning needs to change. Because for the society that we’re living in now, which will be digital going forward. And I’m talking about developed countries, okay? We’re talking about Western European countries, not the rest of the world. That doesn’t mean that the rest of the world doesn’t matter, but this is our most immediate reality.

And in order to raise children and young people to be able to compete in the job market and be able to help us as a civilization develop, our current education system is not tooling sufficiently the bulk of the population, the young population. And that’s not just people like me neurodiverse people, but it’s all, it’s all young people. And so I’m really concerned about that.

And as a journalist, the way in which all the nature of our work is changing or has changed. The skills I learned 20 years ago are almost irrelevant now. I mean your basic core skills, storytelling. Yeah. You have that, but technology, I mean, Hey, it’s completely, it’s completely revolutionized everything. And that’s happening in all sectors.

So I would just say to all parents, that school isn’t enough, particularly for neurodiverse people or children. Learning is key and learning in a way, teaching in a way that your child learns. So I learn through images. So you’ll hear dyslexics say, “oh, I think in pictures.” I don’t think in pictures, I think in pictures, words and sounds. So if I need to explain something, of course, I’ve learned over the years to use vocabulary, to use language, but it’s easier for me to draw a diagram and talk through a diagram. It’s far less stressful. And despite how well I articulate, I articulate better with the diagram.

It’s how you learn that really makes the difference and being confidence in that. So I keep talking about me not having, having a maths GCSE. So that would be like failing your, what do you get when you graduate from American high school, your diploma, your high school diploma? It would be like failing the math portion of your high school diploma.

Carolyn Kiel: So you probably wouldn’t get a diploma, actually. It’s true.

Nadine Drummond: You wouldn’t get a diploma. So technically I would not have been able to get high school diploma here. And so even when I was doing my GRE, I was scoring really low, right? Because I couldn’t do the math section. So I wasn’t able to get a scholarship because England in education, when I was going to school was free. There was no debt, there’s no college debt. So coming to school in America, I needed a scholarship or I wasn’t going to be able to come. And we don’t even have the financing systems to even make it possible.

And so the University of Miami came back to me, despite my rubbish GRE. And they said to me, we’re going to offer you a scholarship. And I was just like, yes! So that’s how I got to go to school in America. And I graduated top of my class, and my comprehension, my writing ability was so high that they couldn’t mark me on the curve with everybody else. Because people, some people would fail the class. So what happened was they had to set up a different grading system for me. So I would get an A plus. So they wouldn’t include me in the bell curve because other people would fail.

Carolyn Kiel: Wow.

Nadine Drummond: So that’s what used to happen in my writing when, when I was, when I was at U M and I’m sure publicly, they would deny that. But I used to get A pluses, and nobody else would get an A plus, so I thought, okay, this is not, I mean, it’s good. But I was like, why am I the only person getting an A plus? But it wasn’t because I was the smartest person. It was just because my writing, that was my superpower. And I knew that as a child. So that’s something that I focused on. It was just something that I focused on. So it was very, very, very, very good at it.

And so people thinking that just because you come top of your class, you’re smartest. That’s not what it means. It just means that you’re performing very well or a very high level in an area you’re good at. And if everybody had the same opportunity to perform at something they’re good at, they would be top of their class too.

So I think the way that we look at success and the way we look at reward changes, or it does, it does change for me. So even when I’ve been a manager in a hiring capacity, of course you have to have a basic skill set, right? But I hire more on teachability and creativity. So what happens is in most places, even at the UN or the United Nations, is that you have to pass a test. If you don’t pass the test, you don’t make it onto the next level because it’s a traditional system. I think that system needs to change, but anyway, it’s not my, I have no power there. Right?

But when I used to do tests to filter applicants, I wouldn’t always choose the top people who gotten the top three. Of course, I choose the top three people because you have to, but I would always pull a fourth or fifth person from the pile, if I could see through that they might have a processing disability or be neurodiverse. And I would always spot the dyslexic or the dyspraxic, and I would always interview them. Because I could see by the way in which they were writing or how they’d run out of time or how creative they were. Because if I’m hiring for a team, I’m hiring my weakness. I’m already clever. I don’t need a clever person. I need somebody that’s creative. I need somebody that’s got the technical skills. I need somebody that is teachable and that is a great team player that is going to bolster our team. So when I’m looking at candidates, I’m looking at them very differently, but I’m always able to spot the neurodiverse people, and I always interview them, even if they don’t come out on top. Because they might’ve just had a bad day that day.

Carolyn Kiel: Right, yeah.

Nadine Drummond: And so that’s what, that’s what I do. And I had to, I have to fight generally my managers to interview more people. And sometimes the neurodiverse person gets the position, even if they didn’t qualify top. Sometimes they don’t because they’re just, they’re just not good enough. So that’s, that’s another creative way which I try and think more broadly about hiring. Because taking the exam and a test doesn’t mean you’re going to be the best person for the job because tests aren’t always the way to choose the best people. It’s, it’s the people that are best at taking tests.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And I just know from school, I was usually pretty good at taking tests, but as soon as you get into the working world, that skillset doesn’t translate in most places where you work. So it’s like, wait a minute. This is a totally different, I need totally different skills and strengths and things to do here.

So yeah, that’s a really powerful way to hire as, you know, hiring for your weakness and, you know, makes a lot of sense. You want to a well versed team that, you know, all your strengths and weaknesses are covered as a team. And yeah, I wish more managers hired that way. I think it’s a great way to hire and team build.

Yeah. So you said that your superpower was writing, clearly, and you really continued to build that through college. So how did you decide to choose a career in journalism and what was it like when you started out in the working world?

Nadine Drummond: So that wasn’t the career that my parents chose for me. I was meant to be a lawyer and I was meant to join the Labor party, which would have been the American version of the Democrats. And then I was meant to be a member of Parliament. I was meant to go to Congress and I was meant to represent my local community. That was what I was supposed to do. And that was actually what I wanted to do really, until I went to university, until I studied law. And I was like, this is for the birds. This is not for me. These people are crazy. There’s no way I’m going to sit with these people for the next 20, 30 years of my life. I will die!

And back then I thought I was so hot. I thought I was just like an it girl. I was like, I’m too fly for this. Like I need, I need more glamour or fantasy in my life. So that, that just, I really didn’t like studying law. And I found at university more creative things. So I, even though I didn’t like my subjects, I loved my university life.

I did lots of student union stuff, student politics. I had a radio show in the morning that used to start at 6:00 AM. And I used to play like hip hop and R and B, which is a big thing because they didn’t even play hip hop and R and B in the clubs in Cambridge at the time. I joined Red TV, which was a TV society. And I learned very early stages of TV production.

And I’d gone to my director of studies at my college. And I said, I don’t like law. I don’t want to study law. I don’t want to be a lawyer. And she said, so what are you going to do? And at that stage, I tried to change to Classics, which is ancient history. I didn’t, she organized it for me and I didn’t have the courage to change. I said to her, I want to be a TV reporter. I want to work in television so I can write, I can use images. I can use sound. I want to tell stories. And she said, so do that then.

And so it was, for her, it was so easy. And she said Nadine, you have to do things you’re passionate about. I understand what your familial expectations are, but you really need to, she said, life’s a long time and you need to do things that you love. And so she made it so easy for me. I didn’t even tell my family, I made the decision. I decided I’d complete my degree in this particular subject. And then I would go to America because there’s no way I’d be able to stay in England and then be like, tell my parents, I’m not going to law school. I’m not going to qualify as a lawyer because I really had no idea where I would live.

So once I won the scholarship, I knew I could go and I didn’t need anybody’s help. Even though I did tell my mom, I didn’t tell my dad. And I basically ran off to Miami. I ran off to UM without my dad knowing, and with my mom obviously knowing. And I, I just got my visa. I organized all of my students stuff and I went to Coral Gables to study broadcast and communications and become a TV reporter, a producer. And it was the best decision I ever made. American schools are designed very differently from English schools, but when it comes to creativity and arts and technical and training, the schools train you a lot more for the, what you need, and that’s what I needed.

And I’m a technophobe. And also because of my dyspraxia, I needed to be somewhere I could actually learn how to do things in a really creative capacity, so I could find out what I was good at, because it’s a lot harder for me to find out what I’m good at in a, in a traditional English context. In America, it’s a lot easier if the gambit you play in is much broader.

And so UM was just fantastic. I could get to be great. I was great at so many things. I’ve never been that great in my life. And then I was like, okay, I’ll stay in America, because I’ll just be great all the time. It was so creative. I could hide my disability even more.

I worked in, I was, I was in America for nine and a half years. Between Florida, between Miami and Atlanta, where CNN is. And I I could be creative. Americans are the best at TV in terms of creative, in terms of production, in terms of innovation. And those are the things I’m good at. I can innovate. I can create. I’ve got ideas for days. I live, I dream, I think TV. It was, it was like my dream come true.

I felt like my first year at CNN, I will say hands down was probably one of the happiest and best years of my life. It was like the holy grail. And every morning I woke up, I felt so, I haven’t been able to recreate that feeling, but I’m working on it. I just felt like this is it. This is the pinnacle. I have arrived. I have made it. And every morning my shift used to start on the weekends, my shift started at 6:00 AM. On the weekdays, my shift started at 7:00 AM. So I was up at like 5, 4:30, 5. Cause you can’t go to work without knowing what the news is. So you’d have to like do work before you go to work. And I was up and it was never hard. I was there. I was living, I was living my dream. And so that was, it was, it was an amazing experience.

And so Miami or Florida, as you know, is a swing state in the United States. And so politically it’s very important. And you can’t work in Miami without understanding the, the political structure of Florida. So I became a Florida expert without knowing, as all journalists that work in Florida often become Florida experts. And I occupied different identities because I was an immigrant. I was also a journalist and I was in South Miami, which was probably one of the most diverse places in the United States with people from the Caribbean and from South and Central America.

And also at that time, Barack Obama was running for his first term and he didn’t look like other presidents. And also his father was an immigrant and he had a foreign name, even though technically my name is not foreign in an American context. And so I was able to develop this niche where I could, and also I still paid attention to news from Europe because it’s home, right? So I had to know what was happening. So the stories that I would go to at meetings and what I would pitch would be completely different. Despite the fact that I was a junior, because I was a baby, because there was some serious stalwarts in the CNN building. And I would just come up with these ideas, that they wouldn’t be able to conceptualize because they were American. And I’m not speaking as an American, I’m speaking as, as a recent immigrant to the country who understands Barack Obama’s difference. I don’t understand his Americanism, but his Blackness or his Blackness isn’t just, African-American, it’s also foreign.

Carolyn Kiel: Right.

Nadine Drummond: And because his father was from Kenya. And so I was able to bring a whole different understanding of what that means for somebody that occupies different identities and even during his term.

Okay. So go back to that. So that actually, all of that work actually earned me a place at the inauguration and I was able to go to the mound. And then it was called I reports. Now it’s just called selfies. Everybody can do them themselves like reels, they’re called reels. Now everybody does it themselves, but then it has to be structured and organized. And I did those for like 10 hours a day from the mall. And it was like, I was on, is it Nyquil? I was so sick! I thought I might die! I was, I’ve never taken so many cold and flu. Like I was so sick. I was sick as a dog and I was doing all that was like, and so at the end of the day, I just used to pass out in my clothes. Then I’d wake up like shower and then go to bed. Like that’s how tired I was. But it was the most amazing experience.

I got to go to a ball. So what happens at an inauguration is you have, because you know, America’s huge, you have different ba lls for different regions of the country. And I went to the Southern, the, the ball of the Southern part of the country and like still dance. And that was just like amazing. I didn’t even have clothes to wear. Like I’d never been to a debutant ball. I’d never been to a ball. All my ball gowns were in England. And it was my show producer, he said to me, look, I’m going to lend you a ball gown, cause you need a ball gown. You can’t wear your crazy clothes. And so I borrowed a beautiful gown from my, my, my, my boss, my producer to go. And she lent me gloves. She lent me jewelry. Even the clothes I wore were borrowed to this inauguration and it was the most fantastic. It was the most fantastic experience. It’s just the most amazing experience.

And so I developed this specialism in Miami and that’s what got me to CNN. So what tends to happen in journalism is that for country or for states that are swing states, you actually need experts and you need people that know who, they know the facebook, the traditional facebook, which is that that’s this person, they’re Democrat, they’re Republican, that’s this person, this is that person’s aide. This is their head of comms. So you need somebody that knows that information without somebody else having to learn it. And I was that person.

But I wasn’t just that person, because I was also foreign. So I could also explain from a British perspective. I could also, I had links within Caribbean communities like all Caribbean, French, Spanish, English speaking in Miami. I didn’t really have any links to South America. Somebody else did that. And also the UK. So I was like this catchall. I was like a unicorn. And so I was able to use my creative skillset really well. So I was able to not have to hide or even work around my disability because I wasn’t doing any work working in my weakness. I was only working in my strengths. And when I walk in my strengths, like everybody else, I’m brilliant.

And so CNN was a wonderful experience, but my drive, I like international news. I’m an international person. And during that time there was the Arab Spring, and the Arab Spring happened. It started in Tunisia where there was a lot of economic strife, like severe economic strife and discontent. And I think it’s called self-immolation where a local guy, I guess that it would be the equivalent of a hot dog guy, set himself on fire, in protest against the government. And then it spiraled around the region. And what we see now today with what’s happening in Syria, arguably what’s happening in Yemen are all linked to the, the Arab Spring. And that’s where the news was and that’s where I wanted to be.

And so I had no contacts, like I’m an American trained journalist. I wasn’t a journalist in the UK, so I didn’t have any of those traditional links. And I definitely didn’t want to go back to England anyway. And I did like my American life, but I wanted to cover these types of stories. And so I decided that I would go and work for Al-Jazeera. And so it took me a year to work to build the relationships, to build the networks and to go. And that’s actually, that’s a good amount of time. It’s an average amount of time. And so I was offered the position and then I was just like deuces, I’m out, bye CNN. And it was very, it was tough leaving. It was really tough. Cause that was that’s where I learned everything that I learned and everything that I use now is still based on that original training, even more so than the time I spent in Miami local TV markets. It was what I learned at CNN.

And then I went to Al Jazeera. I moved to Qatar in the Gulf and I stayed there for three years. And then I decided that I still wanted to niche down and tell more stories about people like me. I’m yes, I’m a Black woman. I’m a Black Caribbean woman from Britain. I come from a Christian background. I don’t have, even though I understand the culture and I speak a bit of Arabic now, I’m still an alien in that space. And I wanted to be an alien in another space or tell stories more about people like me.

And so I moved to Ethiopia and I decided that I would make a film about a group of disenfranchised people from the Caribbean who during the repatriation movement moved back to Africa, that were forgotten. And so I made that my mission over the next five years. And I lived in Ethiopia for for pretty much three years, maybe frankly, the in and out trips, four. And I I, I made this film. I produced this film about this disenfranchised group of Rastafarians who moved back to Ethiopia 60 years ago. And they were the first group to repatriate themselves.

Ethiopia is not a very open country in the same way that Kenya is or that South Africa is. So the people that go there go for specific reasons. So there’s lots of development, infrastructural development. So you can have a lot of Chinese, a lot of Germans because of their engineering, Italians, design engineering, that type of thing. And you’ll have NGOs. You don’t really have journalism. It’s not a free country. And unfortunately journalists are hunted. So I didn’t have my people, my people were not there. And so I, my social group became very German, very Italian, and then NGOs, people from all over the world that would just come to Ethiopia to work.

So I was socializing with a brand new group of people, whereas all of my work life I’d only ever socialize with journalists. And that was it. I didn’t really know anybody. If you were not a journalist, I wouldn’t probably know who you are. Or if I didn’t need you to come on my show.

So I would start meeting. And there were lots of women, in the NGO world there are so many powerful women. Powerful, brilliant, accomplished women that are really saving lives and improving the lives of women and children and men all over the world. And so I was just enamored by so many of these amazing women that I was meeting. And one of them said to me, “look, I need you to pitch for this project. It’s a film. I just need you to pitch for it.” And I said to her, because then my ego, I was like, “oh no no no no, I don’t make NGO films. I’m I’m a real filmmaker.” So she said to me, she was like, so we’re in a bar and she banged the table and she said, “just get over yourself! I’m asking you because I don’t want it to be a normal NGO film. I know who you are. I’ve seen your stuff. Can you just pitch? I need you to pitch cause I need to understand how you can creatively develop this project for us.” And I said, “okay, when’s the deadline?” She said “tomorrow at nine o’clock.” Right. And so it looked, I was like, “it’s seven.” She said, “yeah. So I’ve emailed you the brief. So maybe you should go home and work on it.”

Oh my goodness. And so I did, I left, I left. I mean, I wasn’t, I wasn’t tipsy or anything, but I left. And this is again where my news training kicked in because when you work in news, you work overnight. So it’s just standard for part of your career. And I had, coffee in Ethiopia is amazing. It’s not even, it’s like an elixir, it’s amazing. And so I said, right, so I went home and I read, it was a proper report, like a 10,000 page report. And it was about the, those weapons flow in Sudan, in South Sudan, Libya, and the Central African Republic and how it impacts gender based violence. And I read the report and I was like, this is horrific because then the figures they came up with was that one woman or girl is raped every 50 minutes in Central African Republic.

And so I was like, okay. And I had all of these, I don’t know if you’ve seen Harry Potter where, when I don’t know any of these types of movies, when people think, and all the images start flashing on the screen. And so I visualized the film. It was almost like a projection from my brain where I visualized in half an hour, pretty much how I was going to make this film.

And so I documented it. So I wrote down the treatment. I wrote everything. I sit down. I mean, I stayed up all night till it was done, but what was hard was reading the reports. But in terms of writing the brief, it was literally, it was, it just flowed through my brain. I, I guess it’s called in flow. That’s what psychologists call it. When you’re in flow, it flowed through my brain. And I wrote it all, am I won. I won, I won the contract and I gathered a team. I went to Central African Republic. It’s actually the most dangerous place I’ve been. Even though Yemen was really dangerous, I still felt safe. Well, let me rephrase that, safer than in Central African Republic, it felt like a tinderbox.

And there, the conflict was, most conflicts are economic anyway, but it was also wrapped up in religious difference between Muslims and Christians. And in that country, I look like a Muslim. And I was a target. So this is another thing. Whenever you travel, if you look like the “wrong type of person” you can be done for.

So I, I, I went to the Central African Republic. It was at that stage the most soul-destroying work I’d done in the field. Because the treatment of these women, multiple rapes, was so heartbreaking. And one of the key things in the, in the film was that you have to get water. There’s no running water. You go to a well. It’s been like that for a millennia. And so all the soldiers used to do is just wait by the well. And the women, you can’t fight or you die. You can’t send your son because they’ll take him as a child soldier. If you send your daughter, she’ll be brutalized and probably taken in the bush to be a bush wife, which is where you become a wife to three or four men. And so what happens is these women, these terribly brave women will go to the well, every two or three days, will be subjected to all sorts of sexual assault by multiple men. The men leave, they get their water and they go home, back to the camp. And that was their life. And that was the life of most of the women in this camp. And this camp was a camp which was run by the Catholic church, the Catholic diocese in Central African Republic. And it was the only camp in the country that housed both Christians and Muslims. And so that’s another reason I wanted, apart from the fact that Oxfam had projects at this camp, it was a model for the rest of the country because both groups of people were suffering that were there, and both groups of women were being raped irrespective of their religion. Right? So it was a woman thing. It wasn’t a religion thing. It was just a form of horrendous abuse.

And so that film became very contentious because it wasn’t made in a traditional NGO way. And in the end it won out, because the people who wanted to present a different type of story in a different type of reality to show why these projects were so important. It was used as a high level advocacy tool at the African union and the European union as well. And it helped extend the life of the Water Project. The Water Project was so important. It wasn’t just about having running water. It was about protecting the dignity of these women that were having to leave the camp to go and get water.

And so the film actually extended that Water Project. So if you’re thinking about water project for over a thousand people in the camp, there is a lot of water daily, and that film was able to extend the life of the Water Project, which was ended, which had ended. They, everyone kept saying, no, there’s no more money. There’s no more money. We were like, there has to be more money! There has to be more money! Like we can find the money from somewhere. So that’s what happened.

And that’s when I realized the power of campaigning journalism. So within journalism, there’s lots of debates around whether or not subjective or subjective. And I’ve decided that, and this is also from my local news experience, which I did learn in Miami, which is that you need to give your audience news they can use. They can go to the national outlets for what they need to learn about the country generally or internationally. But in your home communities, you have to give your mom & pop store people, your teachers, your stay at home moms, your soccer moms, your truck drivers, you have to give them information that they can use to improve their lives.

And so I took that really local news training with my desire to actually impact the world. And then it morphed into, some would say what I do isn’t journalism anymore. And I understand that. I’m not trying, I’m not gonna argue with anybody. But I call it campaigning journalism. And so I’m very clear that I have a bias. I don’t pretend that I don’t have a bias, which I think is what some journalists do. I have a bias and I work for my bias, which is that I believe in women and girls education, I believe in women and girls’ rights. So I believe in equal access to education. I don’t support underage marriage. Of course, I’m anti domestic violence. All of those sorts of things that impact us wherever we are in the world, irrespective of our kind of like country privilege.

And so those are the things that I focus on now. So my communications work is still journalists space. It’s still storytelling. So I have very high ethics. I don’t compromise my ethics. That’s something I take with me from working at elite institutions in journalism. But also I’m doing it for a purpose. I’m not just going to tell you what the news is, and then you decide how you feel about it. I’m going to tell you what the news is. I’m going to tell you how it’s impacting these people. And I’m going to tell you what you can do if you want to help.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Nadine Drummond: So I take it in my mind, or my reality, a step further, and then I use my journalism connections because my journalism network is global. And I’ll say, Hey, do you know what’s happening in Yemen? Or do you know what’s happening here? You know, this is a story. Maybe there’s something you can look out for. I know you can’t travel because there’s a media ban or you can’t travel because there’s a pandemic, but there are a few people on the ground that I can put you in touch with that possibly can help you, become sources for your stories.

Now, of course, when I’m pitching journalists or newsroom journalists, that can be problematic because what that will mean is that I’m feeding a story and I’m feeding sources, which is quite dangerous because I can be creating a narrative which is wholly false, which is what happens all of the time. So part of that is based on trust and my reputation that people trust that if I’m pitching them, it’s legit. At the same time, they have to do their own recon, their own research, and maybe not use my suggestions for sources, but find their own. And you can’t take it personally because it’s the nature of journalism. You’re meant to investigate. That’s what you’re meant to do.

And so that’s, that’s, that’s the world, I mean, I’m in now. So I still have a column. I write for Medium, which is an online news, it’s a paid for online news platform. I think you can get one free article a month. And so I write on the things I care about. Race, class, gender, and internationalism.

And I write for a niche kind of American audience actually, write for a niche American audience that are interested in the Black British experience, but how it relates to a broader American experience in terms of history. And that became, I became quite popular as a result of the treatment of Meghan Markle.

Carolyn Kiel: Right.

Nadine Drummond: And people trying to understand, like in an American context, Americans couldn’t understand. Of course they could see that something was very wrong. But most people, I know everyone’s different and they couldn’t understand. So I became the person to help Americans understand why she was being treated so poorly, irrespective of how people feel about her as an individual, but just explaining the English culture and the way in which English discriminatory structures are different from America. And so Americans didn’t feel bad. Because I think generally speaking Americans are made to feel like the worst of everything in the world, which actually isn’t true. Because despite the challenges in America, America has some wonderful, is a wonderfully beautiful enriching place. Right? This is from my lived experience, my, my worldview. And it’s always easier to keep pooping on the, on, on the same people or kicking the same dog because you can. And so I used my, I used, I used my platform to explain that it’s not just you guys, it’s everybody, because this country does this. If you look at the stats here, this country does that. If you look at the stats here, this country does that. If you look at the stats here. If you look at experience by experience. So people could have a greater understanding of how systems and structures work globally, and that these issues, whether it’s sexism, racism, transphobia, homophobia, disability discrimination, whatever it is, it happens everywhere almost to the same extent. It just happens in a different way.

So my, my platform became really popular because I was able to provide context in a way that wasn’t present in a, in a traditional kind of American news context, because newsrooms are only as diverse as the people there.

Carolyn Kiel: Right.

Nadine Drummond: And ideas come from people based on their life experience. So if you don’t have enough women in your newsroom, you are going to fail on particular subjects. If you don’t have enough diversity in your newsroom, or have an inclusive environment where people feel like they can contribute from their very unique perspective, then you’re just not, your news is just going to be a bit crappy. It is going to be rubbish, really.

So, so I’m talking a little about my news philosophy. But yeah, so that’s kind of my news philosophy, but it’s also how I, how I work as well. My work is very deliberate and it’s very passionate and it’s taken me a while to get here, as I think it does in most careers where you get to know who you are. And in a creative endeavor, your work grows with you. Anything creative, your work grows with you. And so my work is just now a manifestation of my growth and who and where I am at this stage in my life journey.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And that’s, that’s fantastic. And you know, when I was reading off your, your bio earlier, when we’re talking about very high level, some of your experiences, but another thing and something that you touched on with your story about Central African Republic and the Water Project, is that a lot of the work you’ve done in journalism and filmmaking communications has, you know, either raised like millions of dollars, it’s changed government policy. It’s saved people’s lives, all kinds of people’s lives in different parts of the world. So it really is just so powerful what you’ve been able to do by really leveraging your strengths and living in your passions. So that, that is really incredible.

Nadine Drummond: Thank you. And it’s, it’s hard sometimes because I mean, it’s always hard, but it’s hard sometimes because, the way in which most of us will think about success and being, success is based on material things, right? It’s based on where you live, the car you drive, your holidays, how you travel, the gadgets. You have these sorts of things. But we’re now talking about the quality of human beings or the quality of, not even, before we get to saving a life, but helping a neighbor. The values that our societies are traditionally built on, right? If you’re from the west, we call them a Christian value system or a, a moral, moral value system. In other parts of the world, it’s a Buddhist system or it’s an Islamic system. But fundamentally it’s about looking after each other and taking care of our families, our broader communities, these sorts of things.

And so. Yes, I have saved lives. Like I’ve actually saved lives. And I can, like, I don’t know how many, but it’s thousands though. I’ve improved the lives of thousands, even many more people, thousands more people. And I’ve prevented women from being, hundreds of women from being raped a whole lot more than they would have gotten ordinarily, I mean, of course saving lives is great, but one of my proudest achievements is I’ve prevented lots of child marriages. I bought girls out of their child marriage contracts.

Carolyn Kiel: Wow.

Nadine Drummond: Girls as young as 8, 9, 10. And those are things that you can’t get from your day job, in that sense. So I do, I feel really accomplished because of those things. So even though I do love journalism and storytelling, even though I do love building strategies, I love training people. I love watching other people employ the skills that they’ve learned from me and generate engagement. I love all of those things, but the things that move my soul are knowing that the work that I’ve done has improved the quality of somebody’s life for them to be abused just a bit less.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Nadine Drummond: And I think parts of that comes with understanding that, while everybody thinks about these things differently, but for me, it’s miracles generally don’t happen as these big things that we’re taught about how they happen. God said, let there be light, and there was light. Yeah, but I can’t do that. I don’t, I can’t say, world peace now, and then you know, the wars are going to stop. It’s not going to happen. Right. I don’t have that power, but what we do have is incremental power.

So in Jamaica, there’s a, an adage which says one one coco fills the basket. So if you put one, I say one apple and another apple and another apple. If you take time, you will fill your basket. And that’s how I see miracles, they’re incremental. So if you have enough tiny miracles, then it will turn into this big miracle and everyone will think it’s a big miracle, and it’s not. It’s because you made a small step doing the same thing or slightly different to get you to this point that you’re trying to reach, to get you to the zenith of whatever, or the summit of whichever mountain you’re climbing. And my work over the years has looked kind of a bit like miracles, but it’s not. It’s, it’s lots of repetitive actions with dedicated people that are willing to learn and be better to improve the lives of others.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And that’s something for everyone to think about as they think about the impact that they want to have on the world. And sometimes these problems just seem insurmountable and huge, but even as you said, incremental changes and those small miracles and those small steps that you take to make things better about the things that you’re passionate about and the problems you want to solve. It’s really powerful. Wow.

Nadine, thank you so much for being on my show. I’m going to put a link to your Medium blog and the article that we talked about before on LinkedIn that you wrote just so people can check that out after the show, but I’m, I’m really grateful for you to about sharing your story and talking about all the great impact that you’ve been able to have on the world. So thank you again for being on my show.

Nadine Drummond: Thank you.

Carolyn Kiel: Thanks for listening to Beyond 6 Seconds. Please help me spread the word about this podcast. Share it with a friend, give it a shout out on your social media or write a review on Apple Podcasts or your favorite podcast player. You can find all of my episodes and sign up for my free newsletter at beyond6seconds.net. Until next time.