Ben VanHook is an autistic master’s degree student studying public policy at George Mason University, with the hopes of reforming employment and education policy to make them more inclusive for neurodivergent individuals. Ben’s passion for creating a more inclusive world stems from his own experiences as an autistic Jewish Asian American adoptee and has led to him speaking and presenting to employers, professors, researchers and self-advocates in the United States and abroad.

During this episode, you will hear Ben talk about:

- How he learned he was autistic while he was in high school

- The challenges he faced coming from China to the United States as an adoptee

- His insights about the intersections of his identities as an autistic, Jewish, Asian American adoptee

- How posting on LinkedIn led him to become a neurodiversity advocate and public speaker on the intersections of autism, race and religion

- His role in a TV documentary about intersectionality between race and autism

- His thoughts on supporting neurodivergent employees in the workplace and in their careers

- What are the main goals for his advocacy

To find out more about Ben and his advocacy:

- Follow him on LinkedIn

- Watch the PBS documentary that featured him: “A World of Difference: Embracing Neurodiversity – Neurodivergence and People of Color”

I’d like to thank Elaine A. and Dan G. for supporting this podcast on BuyMeACoffee.com!

Visit BuyMeACoffee.com/beyond6seconds to find out how get a shout-out on a future episode.

Subscribe to the FREE Beyond 6 Seconds newsletter for early access to my latest podcast episodes!

*Disclaimer: The views, guidance, opinions, and thoughts expressed in Beyond 6 Seconds episodes are solely mine and/or those of my guests, and do not necessarily represent those of my employer or other organizations.*

The episode transcript is below.

Carolyn Kiel: Before we get started with today’s episode, I want to give a special shout-out to Beyond 6 Seconds listeners Elaine Acosta and Dan Gabree, who recently helped support this podcast by purchasing a virtual “cup of coffee” for me on BuyMeACoffee.com! Thank you Elaine and Dan, I appreciate your support. BuyMeACoffee.com is a simple way to encourage and support indie podcasters whose content you enjoy, for the price of a cup of coffee, and it helps defray the cost of producing this podcast too. If you’d like to buy me a virtual coffee and get a shout-out on a future episode, check out the link in the show notes to BuyMeACoffee.com/Beyond6Seconds.

Carolyn Kiel: Welcome to Beyond 6 Seconds, the podcast that goes beyond the six second first impression to share the extraordinary stories of neurodivergent people. I’m your host, Carolyn Kiel.

On today’s episode, I’m speaking with Ben VanHook. Ben is an autistic master’s student studying public policy at George Mason University with the hopes of reforming employment and education policy to make them more inclusive for neurodivergent individuals. Ben’s passion for creating a more inclusive world stems from his own experiences and has led to him speaking and presenting to employers, professors, researchers, and self-advocates in the U.S. and abroad. Ben, welcome to the podcast.

Ben VanHook: Yes, thank you for having me. I really appreciate the opportunity to talk with you about intersectionality and autism.

Carolyn Kiel: I’m really excited to learn about your experiences and your thoughts and, and all the speaking and presenting that you’ve done on those topics. Would love to just start out and learn a little more about you. So when did you realize that you’re autistic?

Ben VanHook: So, this is an interesting question because I didn’t realize I was autistic until I was in high school, but I always knew something was different about me. I realized I was being treated differently from like seven to eight years old. Particularly I found it harder to make friends. I found it harder to keep conversations going. I always had these really niche interests. Like I was really interested in flags of countries. I was also very interested in like the capitals of countries, US presidents, and things that many people knew nothing about.

I also learned away from other, my other classmates. Like from first to sixth grade, I learned in a special education setting with less people. I didn’t know why at the time, but by the time I found out I was autistic, I was able to understand why this was occurring.

But I was also treated differently in school. I was bullied a lot more in elementary school. And there were times when I asked to change the schools, but my requests were always turned down. I went to a middle school and high school that specialized in working alongside and with neurodivergent individuals, but at the time I didn’t know I was being sent there for my autism. I thought I was being sent to the schools to protect me from the bullies. So I thought it was a good choice. I didn’t know it had anything to do with my neurotype.

But only in high school did I learn I was neurodivergent. I think it just came up in a conversation when we were talking about college applications and college programs that would be a good fit. And we started talking about colleges that had neurodiversity programs, that had autism programs, and that’s kind of when I began to understand myself a little bit more and understand what I needed. And learning that I was neurodivergent, it helped me realize the why behind the what. I knew, like my behaviors, but I didn’t know why they were occurring. I didn’t know it was because I was autistic, so it helped me answer a lot of questions and it also helped me connect with other students who were on the spectrum because we could bond over shared experiences.

Carolyn Kiel: Was it a situation where you had gotten the diagnosis earlier in your life, but you just weren’t told until about high school time?

Ben VanHook: Yeah, that was the case. I didn’t really know. I, I think it was because my parents didn’t really know how to tell me and because I, I mean, how do you tell like a five, six year old that they’re on the autism spectrum? I would’ve liked to know when I was younger, because it would’ve helped answer a lot of questions and it would’ve really helped me understand myself a little bit better. And maybe there were situations where I could have handled myself a little bit better, especially with the bullying, had I known that I was on the autism spectrum, but I think they thought that high school was like the right time for me to learn about my diagnosis.

Carolyn Kiel: Right. Wow. Yeah, because you know from a young age that you’re different, but you don’t know why necessarily. So yeah, I can understand how knowing earlier may have at least maybe made you feel less alone, just knowing like, oh, there’s other people who have similar types of challenges and things like that.

Ben VanHook: And I think it could have also helped me when it came to self advocacy, because if I would’ve known earlier, I would’ve like known myself a little bit more and I would’ve been able to better articulate why I may have needed certain supports and why certain things weren’t really working for me.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, absolutely. Wow. So, you are a self-advocate and an advocate now for neurodivergent people, autistic people, and you talk a lot about intersectionality between race and neurotype and, and other intersections, religion as well.

So as well as being autistic, you’re also an adoptee from China. So how has being an autistic adoptee had an impact on your life?

Ben VanHook: Yeah, that’s a really interesting question. I think the intersectionality between adoption and autism is something that hasn’t really been explored as much as I think it should be.

Adoption is one of the only traumas in which the victim is expected to be grateful, and that’s kind of what makes it hard to speak up as an adoptee, because I’m afraid of the stigma behind it, and I’m afraid of being seen as ungrateful for like having a second opportunity at life.

My story actually comes from a train station in Harbin China. I was abandoned by my birth parents, my biological parents, in that train station as an infant, so I never knew them. And I was picked up by someone like catching a train and I was sent to an orphanage. I was an orphan for a year before being adopted. And I think growing up and who I am today is a result of both my autism and my adoption playing a role in my maturation and my growth, and I might present to some people as very, very different from like the stereotypical autistic person. For example, I’m someone who really loves social interaction. I love hanging out with friends. Sometimes I enjoy going to large sports events. I really like soccer and I really like auto racing, so if I get the chance to attend those events it’s something that I always accept because they’re in my interest areas.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Ben VanHook: I also like attending concerts, so there are a few things that other people might find a little bit over stimulating that I really enjoy attending.

I’ve also been seen to be extremely empathetic to other people, sometimes to a fault, where people say I care too much and that I might need to like stop messaging them for a few days. And I think that has to do with not having that caregiver in my life as someone who was abandoned by their parents. I think that this overly empathetic behavior is me trying to compensate for that and ensuring that nobody feels that way, that they have no one in their life.

I also experience many social fears and anxieties, the greatest of which is abandonment. I’m absolutely terrified of being forgotten by my friends, and that can make transitions really difficult for me. Like graduating high school or graduating college was very difficult because I was afraid of being forgotten. It’s, I guess, kind of an out of sight out of mind kind of thing, where I’m afraid that if people don’t really see my presence, they kind of forget about me.

Carolyn Kiel: It’s interesting to see the overlap between what you’ve described and some of the more typical stereotypical things that we think of when we think of autistic people. Like, you know, around empathy, there’s the stereotype of not being empathetic, but many autistic people are actually closer to, you know, to you being like very, very empathetic as you said, almost to a fault.

And yeah, that connection around social interactions as well. And yeah, I can see how being an adoptee and having early, you know, big changes and perhaps you may call it trauma in your life impacts the way that that you have grown up and your worldview and the way that you view relationships and friendships and things like that too.

Ben VanHook: Mm-hmm.

Carolyn Kiel: If you don’t mind me asking, what age were you when you came from China and came to the United States?

Ben VanHook: So it, I think I was about a year, a year and a half when I was adopted. So I didn’t really know my home country. I don’t really have too many memories of it.

But the way I see my experience, I kind of see two different traumas in adoption. The first being the initial separation from my caregiver when I was an infant, and the second was the moment I touched U.S. soil. Having to kind of assimilate to a new culture, having to adapt and adjust, having to speak a new language.

Also having to fit into a society that might not have been as accepting of me, especially when I was younger. So I think that there are a few different ways to separate the traumas that I felt into, like the initial abandonment and the assimilation to a new culture.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And that assimilation I can see, even though you were, you came over at a relatively young age, but that is still a lifelong challenge.

And you know, you also talk about intersectionality between autism and race. So, you know, what was life like for you growing up and now as an autistic Asian American?

Ben VanHook: Yeah, it’s definitely had its challenges. I was bullied a lot in elementary school for my race cuz I went to a school that was majority white and it was just not really a, like a diverse, friendly environment.

And, the next part I want to tell you also kind of goes to my struggles with friendships and trust. That was that some of my closest friends in elementary school were also people who ended up betraying me in the end. And this happened like when I was hanging out with a few of my friends on the weekend. We were playing video games and watching YouTube videos when one of my friends pulled up a video called Stewart goes to a Chinese restaurant. And this video is one in which Stewart, who was the main character, attends a Chinese restaurant. He goes with his father. And when asked what he wants to eat, Stewart tells the waiter he wants a Happy Meal, like one you get from McDonald’s.But his father has to tell him that it’s a Chinese restaurant and they don’t really have a happy meal available. So Stewart then blurts out that I hate the Chinese. And that really upset me, given that was my birth country and the country of origin for me.

The friends I had back then saw that it garnered a reaction from me, and I guess they must have told people at school because before I knew it, the whole grade kind of knew what triggered me. And from then on people, every chance they got, kept saying like, I hate the Chinese, or they said something else that was really hurtful about my race and origin.

And it was especially hard cuz I didn’t really feel like I had any supports. My parents called me overdramatic and they thought I was like fabricating different parts of it, especially when I asked them to go to a different school. And my teachers, kind of, they were bystanders. They just let it happen. They watched it happen and they didn’t really step in or punish the bullies. Instead, what they did was punish me if I reacted. And I feel being autistic and not really having known that, emotional restraint was very difficult for me back then. So it was difficult not reacting to something that was just an attack on my culture.

I tried my best like throughout the years to kind of forget about what happened in the past, and that started working like in middle school, high school, and eventually college. Because things were much more diverse and I was in a much more diverse setting with many different cultures, many different ethnicities. And that really helped me because it helped me feel welcome and helped me just feel connection to others knowing that I wasn’t the only Asian American in my class.

But then in 2019, 2020, covid kind of came to light and hate crimes against Asian Americans started skyrocketing. And there were shootings like in Atlanta, Georgia. And I, all those memories that I’ve tried to repress came flooding back. It was just me trying to relive the trauma of being bullied when I was five or six because a lot of what different political parodies and different, like politicians were saying were really similar to what people were doing to me back then and saying to me back then. So all the memories came flooding back.

And I felt scared. I felt fearful for my safety. And so much so that I ended up forgoing my senior year of college in person. I had to take it virtually cuz I was afraid something bad would happen. So it wasn’t really the easiest, and still isn’t, being an autistic Asian, but I hope that I can like be a role model for other Asian Americans who are neurodivergent.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, absolutely. And it’s just really horrifying that you and so many other Asian Americans and Asian people in the United States have, you know, grew up facing that kind of bullying and that it continues and really escalated with the pandemic. It is just astoundingly horrific to me. And especially when you hear it from your friends growing up, people that you, that you trusted. Those feelings coming back and, and that fear of not having that safety.

And I think it is important that you and other people who have had experiences like you are sharing that, so people can really see the impact that rhetoric has on people. So yeah, I absolutely think that you are a role model for people who are facing those same types of challenges and that same type of racism and hate from people. Absolutely.

Ben VanHook: I think one of the things that people don’t realize is, especially from a young age, that rhetoric stays with you.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Ben VanHook: It’s something that even if you’re not consciously thinking about it, it’s something that just stays with you your whole life and it’s kind of hard to get away from. It kind of becomes one of your demons and one of your insecurities. So it’s really important for teachers and educators to realize this and recognize that in order to like create a safe learning environment for everyone, they have to focus not only on the physical safety and wellbeing, but also the emotional and mental safety and wellbeing of their students.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, definitely. Especially when, you know, when those things happen in school and nobody deals with it. Of course it stays with you. I think a lot of times when that happens, correct me if I’m wrong, but you’re just kind of expected to deal with it and get over it and sticks and stones, whatever those old phrases are. But if nothing changes and you don’t have any other way to adapt or feel safe or change anything, yeah, it really does stay with people and we just see it come up again and again in society. So yeah, that’s a really good point.

So continuing on intersectionality, you also talk about intersections between being autistic and religion. So you’re also, in addition to being an adoptee, Asian American and you’re also Jewish. So what has that been like being autistic and Jewish?

Ben VanHook: It’s really interesting cuz there are, I’m one of the only people in my family who knows how to speak Hebrew.

Carolyn Kiel: Wow.

Ben VanHook: And knows how to read Hebrew and really took time and effort to learn the Hebrew alphabet. And tried like when I was going to Sunday school classes at my synagogue. So I’m one of the people who was able to learn Hebrew, retain it. It’s funny cause at my bar mitzvah I was more worried about the English part than the Hebrew part cuz I’d really prepared for the Hebrew part. And people were asking me like, how do you do it? And I just, it was kind of hard to answer cause like, it was just a language that I had picked up at a young age, so I just found it really interesting that the Hebrew part was easier than the English part at the bar mitzvah. I think that’s something that a lot of other people found funny as well.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Ben VanHook: When it comes to like services, I started remembering like the different parts of the service and the specific page numbers that we had to flip to before we got to each part. So usually I was helping my parents by flipping to the page, the page number, correct page number, like before we got there, so they were prepared. And I remember like, and this kind of has to do with my memory as well, I remembered all the prayers in Hebrew by heart, so I could just go through a whole service and sermon without even having to look at the book and having to like look at the prayers itself, which helped me, like when I was helping other people.

So I think when it came to learning Hebrew, learning my identity, my autism really helped cause I was able to memorize a lot of things. But I was also able to ask a lot of questions that other people might not have thought of. And I was able to question like why we didn’t say different parts of a prayer when we were like in the middle of it.

Cause sometimes we would say a specific like portion of a prayer, but we wouldn’t go through the whole prayer itself. And I began like asking my rabbi, like, why don’t we say the full Lecha Dodi, or why don’t we say like the full prayer for, let’s say Adon Olam? And basically what he said was, not everyone knows the Hebrew parts. So it was a little bit, so they had to kind of shorten it. But he said that I asked some really good questions regarding the prayers.

When it comes to things like different holidays like Passover and Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah, I’m usually like the leader of those prayers cause I’m the person who knows like the order, who’s memorized the order and how the proceedings are supposed to go. So I think my memorization organization are things that have really helped me when it came, when it comes to like the holidays.

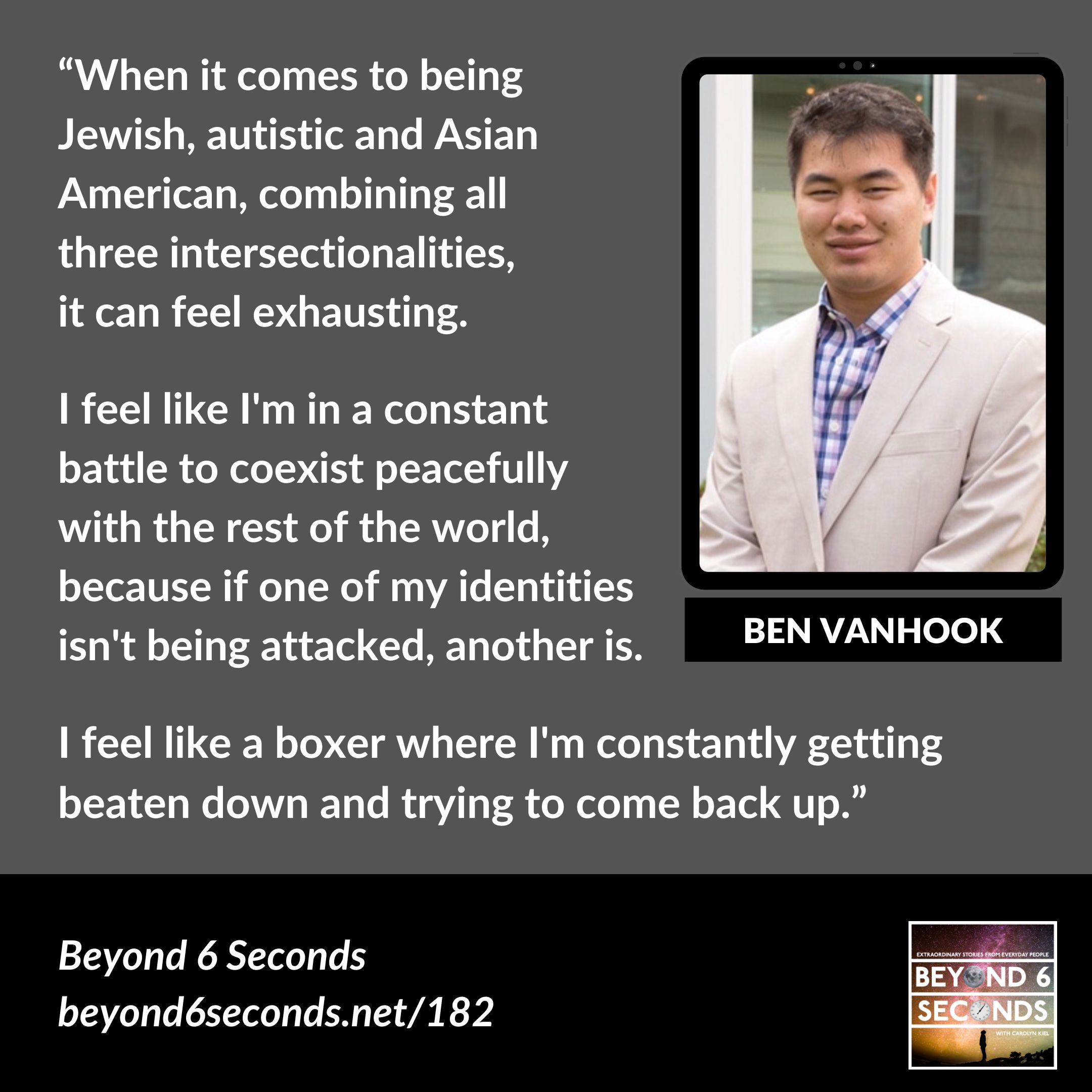

When it comes to being Jewish, autistic and Asian American, combining like all three intersectionalities, it can, it can feel exhausting because it, I kind of feel like I’m in a constant battle to coexist peacefully with the rest of the world because I feel like if one of my identities isn’t being attacked, another is. So I kind of feel like a boxer where I’m constantly getting beaten down and trying to kind of come back up. And that’s been really how I felt the last year or so because my Asian identity has been attacked through Covid. And a year later Kanye West said, has said some really bad things about the Jewish community and it’s led to people, a rise in antisemitism. So it constantly feels like I’m in an ongoing battle to just exist peacefully.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. That’s really, really difficult. And again, that, that rhetoric has real consequences for people. Yeah, I, I can totally see what you’re saying, that you feel like you’re in that constant battle. Wow. Yeah, absolutely.

So, all the more important for, for you to be sharing your experiences like this and in the public speaking and the presentations that you give. As I understand it, you do quite a lot of advocacy around intersectionality and also for more inclusive education and employment for neurodivergent people.

So yeah, I’d love to learn more about your advocacy, what kind of advocacy is it? Speaking? Other venues like that?

Ben VanHook: So it’s funny cuz my advocacy career really started a year ago.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Ben VanHook: So I’m really new to the advocacy field myself.

I was fresh out of college in a pandemic year and I needed a job. So I thought using LinkedIn to network with people and to kind of share my interests and share my values would be a really good place to start because LinkedIn is where we can connect with different employers and where we can connect with like-minded individuals. But I never thought that LinkedIn would lead to me becoming an advocate for the community. I thought that was just a short term thing I was doing to find a job and to be able to pay rent and be able to support myself financially after college.

But I began posting about autism and autism advocacy cuz I knew I wanted to go into the disability field, and more specifically the disability policy arena after graduating college. My degree was in political science and psychology, so I thought it would be a perfect fit. So I began posting things about reform for education, about the need to move beyond the mere acceptance of autism and towards appreciation for autistic individuals and that different schools, different workplaces weren’t doing enough. And eventually my posts started getting more and more traction throughout the autism community and people began seeing my message, what I stood for, and I inadvertently became, started becoming more well respected and well known for my content and I guess I accidentally became an advocate.

When it comes to advocacy, I started out asking people if I could participate in panels or if I could help out with any presentations they were giving. Because I really enjoy public speaking and sharing my perspectives and sharing my ideas with the world. And, it was difficult cuz I had to be patient. But eventually people began seeing what I could bring to the table through my ideas and through what I’m sharing on LinkedIn. And I was offered a few opportunities in like April or May to participate in different panels regarding education and autism and the different supports that I received in college. So I was able to talk about doctors and program at the college and I was able to talk about the vocational trips we took that really helped me develop my soft skills and social skills.

And I think opportunities like bred opportunities cause the people viewing the panel began following me on LinkedIn and began connecting me in with like their organization and with different people they know. So it kind of became an ongoing cycle where I was constantly being introduced to people and getting different opportunities and just being able to pursue my interest, pursue my passions, because people began learning more about me.

When it comes to advocacy in general, I guess my biggest form of advocacy is posting content on LinkedIn and posting different anecdotal stories alongside relevant calls to action. And I think this is one of the most effective ways of communicating and advocating for the community because it’s easy to do, it’s accessible, and people can respond in live time. You don’t have to like, wait for people to email you after a presentation. People can like, comment on the posts.

I also like speaking at different colleges. I’ve spoken at Stanford University and Los Angeles Trade Technical College this past year, and I have a few college visits coming up at Mercyhurst University, which is my alma mater, and Chestnut Hill College in Pennsylvania, which I’m really excited about, in which I’ll be speaking about education reform, transition, and self-determination. I’ve also spoken virtually in Melbourne, Australia around employment reforms and how we can better restructure the hiring process for neurodivergent individuals.

Lastly, when it comes to advocacy, I’ve begun to work in a industry I never thought I would really get into, and that’s media. I don’t really know too much about film production or about podcasts, but I’ve recently really gotten into like the media business. I spoke on a podcast a few, I think about six or seven months ago called Autism Goes to College, which was hosted by the University of California. And this podcast I’m speaking on, I’m with you now is, Beyond 6 Seconds, is my second ever podcast. So it’s just really exciting to get involved in this industry and it’s really cool to learn more about how I can support the community and it’s just a really good learning and growing opportunity and it’s just, it’s really cool to try and learn something new.

Carolyn Kiel: That’s awesome. And speaking of media, I think the post on LinkedIn that showed up in my feed that, that helped me make the connection with you was around a documentary or a special or something that’s coming out in a couple months or later this year. Tell me about that if you, if you can share details on that.

Ben VanHook: Mm-hmm. So I think it’s, I’m not sure when it’s coming out. I think it might be February or March, but it’s a PBS documentary, I mean, it’s by Beacon College in Florida. And the project itself is called A World of Difference. And the episode itself I think is called Neurodiversity in a White World, and it’s around intersectionality between race and autism.

So it, it’s funny, I didn’t have to audition or anything. They just reached out to me on LinkedIn and said like, we’ve seen some of your posts and we think you’d be a really good fit for our TV show. And they just told me what I needed to do, what I needed to prepare for, what I needed to send them. I needed to send them like a headshot and a bio. The process itself was simple and they were able to give me really clear instructions as to what to do and what to expect on filming day, and it just went really smoothly.

Carolyn Kiel: That’s really cool. If the documentary is out by the time this episode’s published, which it might be actually, I’ll get a link from you and I’ll put it in the show notes. That’s a great opportunity. And I think it’s so fascinating that you really built your online advocacy, and in some ways your in-person advocacy, through LinkedIn. Because I think when a lot of people think of autistic advocacy, it’s like all the other social media platforms like Facebook and TikTok and Instagram and Twitter. But LinkedIn, there are advocates talking about it on LinkedIn. I think it’s a great opportunity if it’s a platform that you’re comfortable with and you like the long form writing and the sharing of stories. It’s, you know, you’ve shown it, it brings opportunity. So I think that’s amazing and really awesome that you’ve gotten really great opportunities, not just for advocacy online and virtual events, but also in-person events as well through LinkedIn. That’s really, really cool.

Ben VanHook: Yes, thank you. It’s something that, I look back on it and I’m like, how did I do this? How did all of this come to be? Because it’s just something I did myself. I didn’t really have any help, like with any of this. I was just winging it the whole time, hoping that I would get a job or I would get an opportunity.

And once I started, it’s like I couldn’t stop. I began meeting more and more people, and I began feeling a sense of community. I began feeling like a sense of belonging on LinkedIn because I began to find my tribe and I began to find like-minded individuals who supported a lot of the same goals and missions I did. So I think that being able to find my tribe on LinkedIn has really helped me when it comes to advocacy and when it comes to the hard work that accompanies it.

Carolyn Kiel: That’s great. Yeah. That’s great that you’ve been able to find the people around you and build that community on LinkedIn, cuz there’s, there’s a lot of great people doing great things on LinkedIn. Absolutely.

Ben VanHook: There’s so many great self-advocates and I’m always learning every single day because people are posting different articles and different blogs that, that they’ve written. And it’s really interesting cuz even though there are a lot of self-advocates, they all have very different experiences.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Ben VanHook: and they all have just a very different story to tell. And that’s what makes it so interesting advocating for the community is realizing that not everyone has the same experience as you, and not everyone has like the same needs as you, but it’s important to like, take in their story and just remember these stories when it comes to advocacy. And it also makes advocacy much more personal because you can attach a name to your advocacy work and you can attach a specific story to, like a proposal or an idea that you have. So it definitely adds a really personal element when it comes to advocacy work.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, absolutely. You really get to know people on that platform through their stories and hear those different experiences. Yeah.

So what are your goals overall for your advocacy?

Ben VanHook: So, my biggest goal is to transition society away from awareness and acceptance and towards appreciation.

Carolyn Kiel: Mm-hmm.

Ben VanHook: I think that appreciation and acceptance are very different, and the way I distinguish it is acceptance is hiring because you have to, whereas appreciation is hiring because you want to. I see acceptance as the bare minimum that society can do to support neurodivergent individuals, whereas appreciation should be our goal and should be what we’re ideally striving for.

And some of the specific ideas of implementation I have are things like universal design for learning, both in schools and the workforce. I also think it’s important to advocate for disability in DEI initiatives when it comes to employment. Especially when it comes to reforming hiring practices and supporting neurodivergence in the workplace.

I think a lot of DEI initiatives for neurodiversity in the workplace center around hiring. But I think that instead of hiring, we should focus on retention and we should focus on ways we can keep neurodivergents in the workplace. And in keeping with that, one of the ideas I’ve been pushing for are neurodiversity advisory panels in different organizations. I feel like advisory panels could really help DEI hiring practices because they can talk to board members and people who are running the organization as to the challenges that the, the neurodivergents face when it comes to their own onboarding, and when it comes to the hiring. And it can also increase retention because it gives neurodivergents an ally in the workplace and it gives them some, like a safe space to talk to and go to, to talk about certain issues they might be having. So I think that a neurodiversity advisory panel in different organizations can really help both retention and the recruiting process.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, absolutely. And yeah, I think there has to be more of a focus beyond just hiring, because you know, once you bring people in, how do you retain them? How do you manage them through promotions and job changes and bring them into an environment and culture where, you know, people can thrive and use their skills and get the accommodations or any adjustments that they may need in order to, to really work to their strengths.

And the thing about, you know, neurodiversity and disability in general is that it’s not a monolith, like people literally come with different strengths. So there’s no single hiring solution. And sometimes I see that with companies, I won’t name any names cuz I’m not really familiar with those programs, but a lot of times it’s very narrowly focused on, you know, one specific type of individual or one specific type of skill set or industry or type of job. And it really, you know, as we were saying, it has to be a lot more broad than that and across the entire talent management cycle. Yeah.

Ben VanHook: Yeah. And I think that’s an important point you bring up, that there’s this like stereotype around neurodivergents that we’re like specialists in certain industries, but when in reality, that’s not the case. In reality, we can be good at many different things. It’s not just like the tech industry or it’s not just a certain skillset that we have. I think that the danger different organizations run into when hiring a specific type of individual if they commit to hiring neurodivergents is the stereotyping of neurodivergents and the skillsets that they bring.

So I think that’s one danger. I do think that it’s really important to include specialists in the job. One of the difficult parts that I found in employment was that we had to be good at everything. We had to be good at so many different, very different tasks. So things like social media, things like publishing things on someone’s website. You had to be good at things like coordinating with different people on email. So there were so many different tasks that were just not very similar to each other that you had to be good at. And I feel like that’s not really, that can be difficult for neurodivergents because a lot of neurodivergents are specialists in different areas.

And I think there are different approaches to management we can take. I feel like there’s this jack of all trades approach where you expect an employee to be like, good at everything. And then there’s a strengths-based approach where you can focus in on a employee’s strength, and kind of nurture that and see how that strength can benefit the organization, how they can fully maximize the potential of the individual by using their strengths. So I think a strengths-based approach to employment is really important to consider when it comes to hiring people.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And then you get into the whole concept of helping people become managers and leaders. You know, a lot of people join as individual contributors where they’re focused on certain strengths. And then, you know, I guess it’s a challenge for everyone, but especially, potentially if you’re neurodivergent, if you wanna move up and manage people. Because I feel like a lot of people don’t think of autistic people as people managers. But in fact, I think quite a few of us are. I’ve probably had some neurodivergent managers. They may not have known they were neurodivergent, but I’m like, yeah, I think they were, and I actually really enjoyed working with them. So I think being able to provide those skills as well. And that may just be part of normal talent development once you’ve been in a company for a little while, just to continue career development and career paths. Yeah.

Ben VanHook: And I think when it comes to things like promotions and working your way up the ladder, it should be gradual. It shouldn’t just be like flooding you into completely different job. That’s my fear when it comes to promotion, is that like, what if this job’s completely different? What if I have none of the skillsets required for this job? What if I’m really good at the job I did prior, but this promotion isn’t really working out because it’s so different? So I think that when it comes to things like promotions, organizations should be very wary that large changes can be really difficult for us. If our tasks vary greatly from a previous job, it can be really difficult to adjust.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, yeah, definitely. And, and that movement from individual contributor to people manager is jarring really for anyone. I think any kind of program that helps neurodivergent people sort of through that transition, you know, like with a lot of other accommodations we see, it winds up helping the broader community of employees as well. So yeah, definitely important to help through that transition for people who want to be promoted and want to be people managers.

Ben, thank you so much for talking more about your advocacy on the show. So how can people get in touch with you if they wanna learn more, like read your writing, if they want you to speak on a panel or for an event, where can they find you?

Ben VanHook: So I’m most frequently on LinkedIn under the handle Ben VanHook. You can also contact me at vanhooksiel at gmail dot com. That’s V A N H O O K S I E L at gmail dot com.

Carolyn Kiel: Okay, perfect. Yeah, I’ll put that in the show notes so that people can find your contact info there. And as we close out, is there anything else that you’d like our listeners to know or anything that they can help or support you with?

Ben VanHook: I think it’s important to know that neurodivergents can do anything under the right environments, under the right conditions, and that we are just as capable as neurotypicals when it comes to doing different tasks and completing different jobs. I feel like when it comes to advocacy and when it comes to supporting the neurodivergent community, the best thing we can do as neurodivergents and neurotypicals is listen to one another. I feel like even though this might seem simple, it’s something that’s rarely ever done, and I feel like if we listen to each other and take time to understand each other’s neurotype, if we can even collaborate on different projects together, we’ll be able to create a more inclusive environment than if we kind of separate each other off, separate from each other.

So I think the way we can create a more inclusive environment is to work together alongside each other on different projects and learn more about each other, and establish those bridges, establish those connections through neurotypicals and neurodivergents working alongside each other. I feel we are stronger together then either community is apart. We are stronger united than we are divided.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, absolutely. And we could all play to our strengths, use our strengths, and learn from each other and build things together better united, as you said, rather than divided. Absolutely.

Well, thank you so much Ben. Thanks for being on the show, and it was great talking with you today.

Ben VanHook: Yes. Thank you so much. I really appreciate the opportunity to talk with you and to share my story and to share my experiences. I really appreciate it.

Carolyn Kiel: Thanks for listening to Beyond 6 Seconds. Please help me spread the word about this podcast. Share it with a friend. Give it a shout out on your social media, or write a review on Apple Podcasts or your favorite podcast player. You can find all of my episodes and sign up for my free newsletter at beyond6seconds.net. Until next time!