Why has public discourse about autism been dominated by non-autistic voices? And, what’s been happening recently to change this?

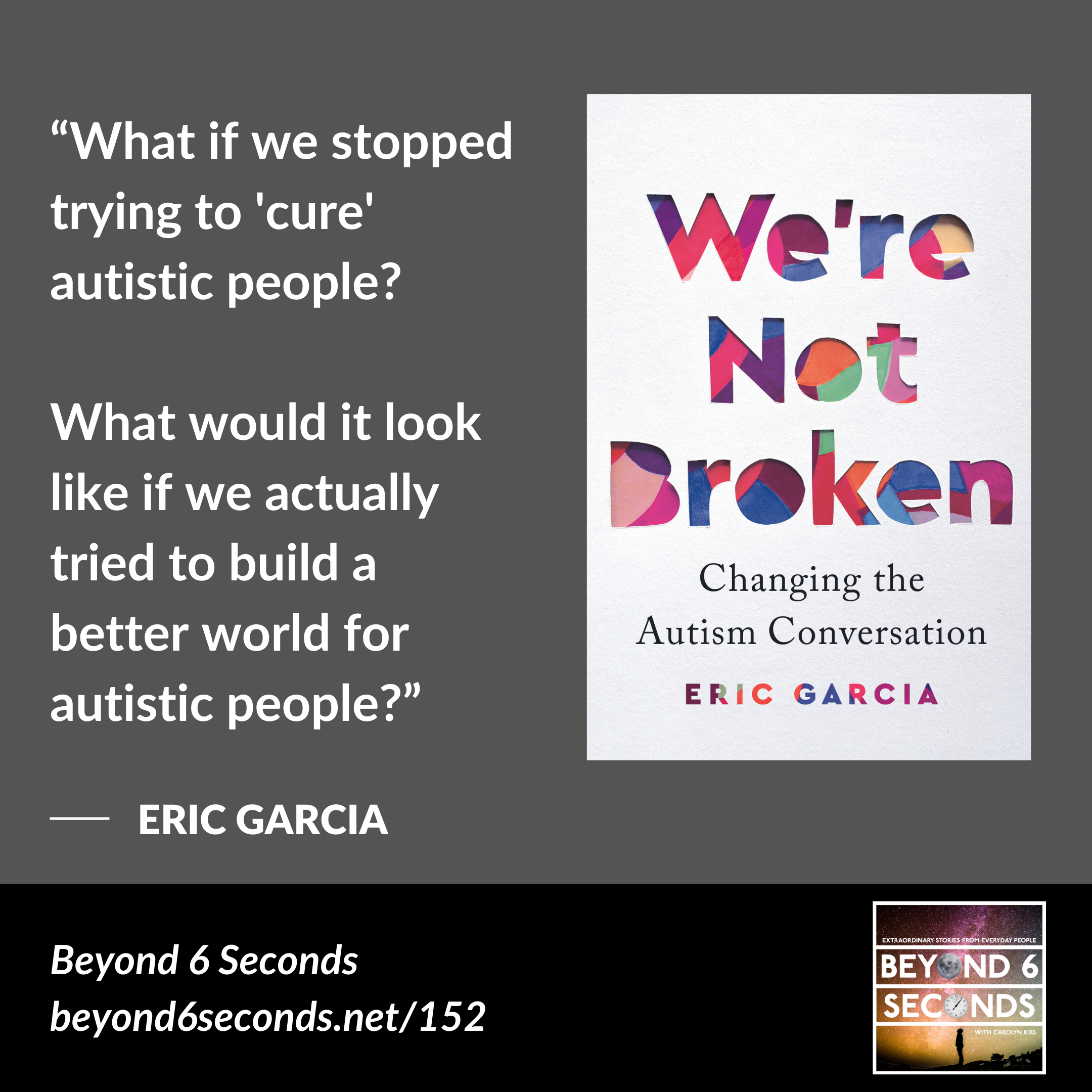

My guest Eric Garcia breaks this down in today’s episode! Eric is a journalist based in Washington DC and the senior Washington correspondent for The Independent. He is also the author of the book, “We’re Not Broken: Changing the Autism Conversation” which was published in 2021.

During this episode, you will hear Eric talk about:

- Why non-autistic voices have traditionally dominated the public conversation about autism

- How government policies have shaped and evolved the public’s perceptions about autism

- Including a wide variety of autistic people’s experiences in his book – including non-speaking autistic people – as well as his own experiences as an autistic Latino man

- How writing this book helped him confront some of his own biases – and what he learned about becoming a better ally and learning from criticism

- Where the public can find accurate information about autism and the autistic community

- How social media has helped autistic people share their experiences, amplify their voices and effect change (for example, by calling out harmful autistic stereotypes about autism in a recent movie by a certain singer)

Buy Eric’s book, “We’re Not Broken”

Read Eric’s National Journal article (the precursor to “We’re Not Broken”)

Check out Eric’s recommendations for other autism resources:

- The Thinking Person’s Guide to Autism

- Sincerely, Your Autistic Child

- #ActuallyAutistic: hashtag used by autistic content creators (good when you want to listen to autistic people, and especially if you’re new to being diagnosed autistic)

- #AskingAutistics: use this hashtag to post questions you want to ask autistic people

Subscribe to the FREE Beyond 6 Seconds newsletter for early access to my latest podcast episodes!

*Disclaimer: The views, guidance, opinions, and thoughts expressed in Beyond 6 Seconds episodes are solely mine and/or those of my guests, and do not necessarily represent those of my employer or other organizations.*

The episode transcript is below.

Carolyn Kiel: Thanks for joining me for the show today! As you may know, April is Autism Acceptance Month, or Autism Awareness Month, as it’s sometimes called. As an autistic person who hosts a podcast about neurodiversity, I’m already aware of and accepting of autism no matter what month it is. But this designated month gives me a good excuse to feature some extra episodes featuring autistic guests with a variety of backgrounds and experiences. I even recorded a solo episode that came out right before this one, where I share some thoughts about autism, and specifically the word “autistic.” You’ll be able to find these episodes, and all my other neurodiversity episodes, on my website at beyond6seconds.net or by following my podcast in your favorite podcast app. And if you want to know about new episodes before they come out, subscribe to my free email newsletter to find out! The links are in the show notes of this episode.

I am super excited about this episode, because today I’m interviewing Eric Garcia, a journalist and author of the book “We’re Not Broken: Changing the Autism Conversation”. I read this book when it came out last year, and it’s taught me so much about the history behind our society’s views and treatment of autistic people, and how public discourse about autism in the United States has been shaped by government policy. We talk about some of the topics he covers in his book, as well as how he started writing about autism in the first place.

Eric covers politics as a journalist, so you’ll hear some political talk during this episode. We also talk about some other hot-button topics within the autistic community, like a certain prominent autism organization and a certain singer who made a certain movie last year that didn’t go over too well – if you’re not sure what I’m talking about right now, just stay tuned to this episode and you’ll get to hear more about it.

If you’ve ever wondered why, until pretty recently, the public discourse on autism has been dominated by non-autistic people – well we talk about that too… how power and influence determined who “got the microphone” when it comes to talking about autism, and fortunately, how that’s starting to change as more and more autistic advocates find platforms for their voices and words. Today, we have the microphone.

Here’s my interview with Eric.

Today I’m really happy to be here with my guest, Eric Garcia. He’s a journalist based in Washington, DC and the senior Washington correspondent for The Independent. Previously, he was an assistant editor at the Washington Post’s Outlook section, an associate editor at The Hill and a correspondent for National Journal, MarketWatch and Roll Call. He has also written for the Daily Beast, the New Republic and Salon.com. Eric is the author of the book, “We’re Not Broken: Changing the Autism Conversation,” which was published in 2021. Eric, welcome to the podcast.

Eric Garcia: Thank you for having me.

Carolyn Kiel: I’m so excited to interview you. I have the audio version of your book and I’ve listened to it twice and it’s just really just such a great work. And I’m excited to share it with my audience and learn more about your process for writing it.

Eric Garcia: You know, like recording an audio book is such a surreal experience. Like, because the mics are so hot, you can’t move at all. Otherwise the mics will pick up your movement. And like you had to eat when you’re hungry, because the mics would pick up your stomach growling. And like you had to constantly be drinking water or otherwise you get dehydrated. And it was like all of these things. And then when I would come home, I wouldn’t speak. It was all of these extra steps that you had to take to record it. So yeah. So I appreciate you listening to the audio version.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. I didn’t realize how hot the mics were. And it’s true, even though, you know, I do an interview podcast, so I don’t do most of the talking, but even if I have to record like a five minute bit after a while I’m like, oh, my voice is tired. And I feel like my mouth is dry. And it’s like all these things, you know, and I’m a singer. So I’m technically, I should be trained with the breath support, but it’s hard to talk. And I can’t imagine. How long were those recording sessions when you had to do that?

Eric Garcia: So I did them for like three days in a row and they would go from like 9:00 AM to 3:00 PM a day.

Carolyn Kiel: Wow.

Eric Garcia: Yeah. They were like six hour days.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, that’s intense. Yeah.

Eric Garcia: Yeah it was intense.

Carolyn Kiel: Right. Yeah. Well it’s, it’s really great. And I’ve listened to it twice, so I really enjoyed it.

Eric Garcia: Thank you very much.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. So, you know, as an accomplished journalist, you’ve been a journalist for your whole career, but you didn’t start out writing about autism. So what inspired you to start writing about autism?

Eric Garcia: No, I, I didn’t really want to write about autism at all. I wanted to write about economic policy and politics. You know, I was perfectly happy. I was working at National Journal at the time. I was happy covering econ policy, politics. I was really early in my career and that was around the time when if you covered finance or you covered banking, any event in Washington, you’d inevitably run into Elizabeth Warren. And anytime you covered anything about organized labor, you’d inevitably run into Bernie Sanders. So like oddly enough, because I was a junior in my career, because like the more senior people were covering Hillary Clinton, I was covering Warren and Sanders a lot. And this was like in 2015, and I was perfectly content to do that.

Then I was at a party. I was like, I was 24 at the time, and a friend of mine offered me a drink and I said, “oh, I can’t drink because I’m on the autism spectrum, and the medicine I take doesn’t mix with alcohol.” And instead of saying, “oh come on, have a drink, you know.” He was like, “oh, that’s interesting.” A guy by the name of Tim Mak. He’s now at NPR. He just wrote a great book about the history of the NRA called Misfire. I just need to plug that book because it’s a great book. I recommend people read it. He was like, “you should write something about that, because there’s a lot of autistic people in Washington.” And then he pushed on me again later. And then I was just like, “nah, you know, when I get good at my job, when I get better.” You know, I was new in my career. I didn’t want to be labeled that. In fact, I’d argue that I spent a lot of time trying not to be seen as, you know, the autism reporter or the autism guy, you know, I didn’t think of it. I tried to not let people know when I was in college, early on my career.

And then what happened was, National Journal the print magazine was going to close down at the end of the year. This was in 2015. So I wrote mostly for the website, but the print editor, a guy by the name of Richard Just, a lovely person, he said, ” pitch me ideas because I’m, I’m going to be out of a job at the end of the year. So like, what are they going to do? Fire me?”

And so I pitched this idea to him about like, what’s it like to be autistic in Washington DC. And he was like, “that’s all right.” And, you know, I thought it would be like a really fun kind of chatty piece, you know, kinda like, you know front of the book kind of piece. And then he thought we could do better. He was like, “why should this piece exist?” And I said, “well, I think we spent too much time time trying to cure autism and not enough trying to ensure that autistic people live fulfilling lives.” He’s like, “there’s your piece. Go.”

And around that time, It was really interesting time when it came to autism. Because if you remember, this was in 2015, this was when Donald Trump was running for president. When, I should say this was around the time that, I should be clear, this was around the time when Donald Trump was seen as a serious candidate for president of the United States when he was no longer see like I think when he first announced there, it was like Donald Trump running for president? You know,

Carolyn Kiel: When he went down the stairs or the escalator?

Eric Garcia: And then, but then like, he started leading the polls. And then I remember one debate, Jake Tapper asked him about his old tweets about vaccines and autism. And of course, Trump being Trump, he didn’t back down. And he said, you know, autism has become an epidemic. He said that autism is you know, he talked about the vaccines and he talked about you know, a friend of his who had a beautiful baby who, you know, got, you know, a vaccine, you know, that looked like it was meant for a horse and then, you know, got a tremendous fever. And then the next day was autistic or something. And, you know, Trump is Trump.

So I wrote, so I wrote that piece, you know, and it blew up obviously. And then my friend of mine introduced me to his agent and she said, do you want to do a book on this? But I think the thing that was interesting was that I probably would’ve sold more books if I’d said, you know, ah, look at, you know, Donald Trump is a conspiracy theorist and things like that. Or if I focused more on Trump. But the thing about it with Trump is that yes, he’s a habitual liar, but he doesn’t pull these things out of thin air.

Carolyn Kiel: Right.

Eric Garcia: There is a cycle that happens where it ultimately ends up, you know, on Donald Trump’s Twitter feed before he got his Twitter feed taken away. So that said to me that he’s a conspiracy theorist, you know, and how did these conspiracy theories foment on the right? And then also I grew up in Southern California, you know, and I know plenty of, you know, liberal hippie dippy people who believe that vaccines cause autism because of “the toxins,” you know? I know Los Angeles and Long Beach and that kind of scene.

But underlying it, what I realized was that underneath the vaccine autism lies and mistruths and myths, there is a fundamental argument, which is that it is better, there’s this argument that it is better for your kids to get measles and die than it is for your children to be autistic. That’s the underlying argument of anti-vaxxers.

Carolyn Kiel: Right.

Eric Garcia: And that really kind of, so, so I wrote that piece and then I think the question was okay, well, what if we stopped trying to cure autistic people? What would it look like if we actually tried to build a better world for autistic people? So that led me to kind of hit the road. And so I went to Nashville, Tennessee. I went to Michigan, I went to West Virginia. I went to the Bay Area of California. I went to Pittsburgh. I spent a lot of time in Washington, which is where I live. And, you know, I kind of just, kind of decided to look like, what are the social gaps that exist for autistic people? But more important than that, what would it look like if we built a world for autistic people? And I think that is the underlying question that I, that I set out to explore writing this book.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And your book really tells that a very robust story about, you know, really about how the public discourse about autism evolved over time. Over the past century, I guess, close to a century now, at this point. You’ve got historical context, political, sociological, and you really touch on all these different areas. How did you pick the topics to cover in your book? Because you really cover a broad swath.

Eric Garcia: All a lot of them I knew I wanted to do from the beginning. Like I wanted to do something on work and I wanted to do something on, I think what I really wanted to do is I want to address, and this is more of the work my agent, Heather Jackson, she said like, “why don’t you pick some things where there are the most common myths and then look at how those myths cause harm?” And I think that was a really, I think that was a really productive way. So I have to credit my agent with that, heather Jackson. And it was interesting because initially I didn’t want to do a chapter on relationships because I didn’t think it was really political, but then, you know, that wound up I think being one of the best things that I’ve ever written. Don’t cheat and go into that chapter! Read all this stuff before, you know, I’d like to tell your listeners.

But like, but like on top of that, I think what I wanted to do is, I think, you know, I’m a political reporter at heart. And, you know, that’s what I do. And I mean, I’ve been, I’ve, I’ve covered economics in the past. So I think what I looked at was you know, the state of autistic, the state of the autistic union, so to speak, is determined not oftentimes by anything that disabled people or autistic people do. Oftentimes, it’s a consequence of policy. So I think what it was really easy for me to do was it was easier for me to look at: this is the outgrowth of this, of X policy, or this is the outgrowth of this bad idea about autism.

So for example you know, I think when I wrote, when I write about in my chapter about work, there is this idea that autistic people can’t find work, or if they can only find they, they’ll only be able to find work in places like Silicon Valley or in STEM subjects. So, what it did is I wanted to find out is that like, I think that that was a really easy thing for me to do was like, well, I know a lot of autistic people live in poverty and I know that we don’t really know the real unemployment rate for autistic people. And at the same time, there’s almost kind of this bifurcation of autistic people, where you have a lot of autistic people at the top who are working in Silicon Valley and Palo Alto and, and, you know, and it’s not just, I just say, you know, not just in tech, a lot of them work in finance. A lot of them work for like EY or UBS or a lot of financial companies. Like in hindsight, I covered a lot of high-frequency traders early in my career. And I’m convinced that like about half of, a lot of the people who were involved in high frequency trading are probably on the autism spectrum or something like that. You know, I’m not a scientist. That’d be irresponsible for me to say, like, in hindsight, like later on when I was writing about it, I was like, oh wait, you know, a lot of them would just like, when I would talk to them on the phone recording, they would like talk my ear off for 30 minutes and I wouldn’t get a single question in. So it’s like, that was just that, that was just you know.

But then on top of that, like there was like, there’s this priority to really hire a lot of autistic people and then, conversely, there’s a lot of autistic people who have intellectual disabilities, who have trouble graduating college. There’s a lot, a lot of them wind up in sub-minimum wage labor. And that’s a deliberate policy choice because the only way you can pay someone below minimum wage labor, and I think a lot of people don’t recognize this, is because there was a law that allows it. The Fair Labor Standards Act that was passed in the 1930s, signed by Franklin D Roosevelt. And it has led to a lot of autistic people and a lot of disabled people as a whole being paid pennies on the dollar. Pennies per hour, not even a dollar but per hour, because that’s seen as the compassionate thing to do. So I think the thing that I really wanted to do is show that these things exist for a reason.

If autistic people wind up in a group home that’s because Medicaid is an entitlement, if they are in a group home, or if they’re in a congregate setting. They waive their rights as an entitlement if they want to have, received home community services. That’s a policy choice.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Eric Garcia: The reason why you saw a lot of autistic people get diagnosed in the 1990s and why there was this fear of an epidemic was because the Individual Disabilities Education Act included autistic people in a way that its previous iterations under the Education For Handicapped Children Act didn’t include. That’s again, that’s a policy choice.

I think that as a political journalist, it was a lot easier for me to look at things through a policy lens, and say that we’re here because of deliberate policies. And I think it’s a more important because these things don’t happen on accident.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And it was really interesting to see how those policies tied together and shaped the whole history. And also how different voices, like certain organizations and certain people who talk about autism and seem to provide like sort of the de facto opinions about autism, tend not to be autistic or disabled people, but are organizations that came in with a lot of influence and wealth, things like that.

Eric Garcia: I think let’s talk about the, let’s talk about the big, the big elephant in the room. Let’s talk about autizmspeekz. I won’t get you sued. But I, I think that, like, it’s important to talk about. Like, again, if we’re going to talk about policy, let’s talk about who can influence policy.

You know, it helps a cause if there’s a really wealthy benefactor. There’s a lot of political connections. And in the case of autizmspeekz, it was started by B0bRite, the head of NBC Universal, who was incidentally the head of NBC Universal when Donald Trump was doing The Apprentice. And I write about that a little bit in the book. And his family could have influenced his ideas about autism, influenced Trump’s ideas about autism, I should say. I think that it’s important to recognize that because he had those political, those connections as a businessman as, and as, he had this kind of perfect intersection as head of NBC Universal, having connections within business and media and politics in a way I don’t think any other person could have. And I I I combed through his memoir when I was writing this book. So like, I mean, it was really important for me to go through his memoir and read it. But I think it was important to, I think that it’s important to recognize that a lot of times, even if you have the best intentions, it can lead to harmful ideas. And I think that is what sometimes has happened, or even, not even necessarily harmful ideas, but just ideas or harmful policies, but ones that just don’t affect autistic people in their daily lives.

For a long time, autizmspeekz was focused on curing autistic people. They removed that language in 2016. Incidentally when Trump was talking, you know, talked about it a year later, but, you know but like, like in 2017, he talked about curing autism or finding treatments for autism. But like you know, by then, autizmspeekz had already removed that language, but it shows how prevalent those ideas can be, how they can spread and how political power, which I think is really important. I don’t think you can talk about politics without talking about power and access to power and access to capital. And I think that that was something that I wanted to do is highlight how, and again, I want to highlight how power works, how power influenced how we talk about autism.

And I should say that it would be easy once again, to just blame autizmspeekz. And I think for a long time, there was a focus on that, but I think it’s important to recognize that there were organizations long before that, that had bad ideas because they didn’t include autistic people. Whether it was Bruno Bettelheim or whether it was Bernard Rimland you know, or the early incarnations of what would later become the autism s0ciety of America, when it didn’t include autism, autistic voices for a long time. Now it kind of does. But it’s important to remember that these, that it was an outgrowth that for the longest time, the people who were considered the gatekeepers both on when it came to knowledge, when it came to policy, when it came to money.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Eric Garcia: Were often not autistic people. And I think that that’s really important. That the, the, the ways that I think it’s a really important, because I think as a journalist, I think about this a lot, I think about it regularly. That oftentimes, it sounds almost contrarian or paradoxical, but oddly enough, journalists need to not know stuff to do our jobs. We need to say, “what’s going on and how do we, why is this thing going on?” And then what we need is we need to rely on experts who can tell us things. I think for a long time, the people who were the experts were clinicians, nonprofit advocates, parent advocates, and as a result, but not really autistic people themselves. So as a result, that shaped how, that shaped media coverage for autistic people. That shaped how it was. Because if these groups had capital, they had money. They had influence, they had research dollars or they put out research studies and things like that, that gives them credibility. And I think it’s really important to recognize how that influenced media coverage. And I’m a journalist. So I think about this a lot, but I think that was really important to talk about.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, that’s really interesting. And I think it’s just not something that people are aware of or, or, or consciously think about. So it’s really interesting to hear it framed in that way. And in addition, you also share a lot of your own stories and your life experience in this book. So what was it like reflecting back on your own experiences as an autistic person and then sharing a lot of those experiences publicly in your book?

Eric Garcia: You know, I didn’t want this to be a memoir. I think that was really, I don’t have anything against people who’ve written, autistic people who have written memoirs. I think a lot of them can be very clarifying. I think that they can be, I think that they were often an important corrective to the idea that autistic people couldn’t speak for themselves,

Carolyn Kiel: right,

Eric Garcia: for a long time. Don’t so, so I don’t, I don’t want to come out as, I don’t want to come off as like I’m an anti memoir. I just think that it was, to me, the thing of it is, is that as an autistic person, I think the thing that I realized when I started writing, I think initially when I wanted to write this book, I think I might’ve wanted it to be more autobiographical. But then the thing that I realized was, I was like, “but does this represent, is this indicative of other autistic people’s experiences?” And then I think what I did was that any time that I then, so anytime that I thought about my own experiences, I would try to like corroborate and like interview other people or read other research. It’s like, okay, this is a thing, or, oh, this is just a me thing.

I think also what it required is that, it required me being brutally honest with like, you know, if I’m going to be a journalist and I’m going to treat this as a journalistic venture, I think this is one of the difficulties with the memoirs is that memoirs, you tend to put yourself in the best light because you want to, and because our memory, we’re biased toward looking at ourselves in the best light.

But I think one of the things I, I really wanted to do that I really tried to do was I really tried to be as honest with myself as possible. And also like, there were times where like, I think as I got older, I realized, oh, that was something where maybe I was in the wrong. Or that was something where maybe I wasn’t as generous to myself or, oh, you know, now that I know more about autism, like that might have been a thing that I didn’t think was a thing.

So in some ways I was more generous with myself. In some ways I was much more critical of myself. And I don’t think that I could have written as good of a book if I hadn’t been both those things to myself, a bit more charitable to myself. And I think also contextualized those experiences within the larger autism experience. And I think that was in and of itself really important. And I think the reason why, anytime that I, and I think one of the things that I always wanted to do when I included anything autobiographical is I didn’t want it to be about me as much as I wanted to use it as a launching off point to make a larger point. So that if there was something that I experienced, that a lot of autistic people experienced at large. I wanted to use that as a starting point to discuss something. But if my experiences were were an outlier or unique to me, I think it was important for me to say “this was unique to me, but that’s not the case for a lot of all the other autistic people.” And then for everything in between I tried to do, you know, a little bit of both. But I think that was really the, if I was going to do anything autobiographical, I think that, I think I always wanted to contextual it.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, and I think that’s great because you really weave in a lot of, you know, personal stories and experiences of people, you know, not just of yourself, but the other people that you went out and interviewed and sort of put it in as real examples of what this policy looks like, how this history came about and what’s going on in society, things like that.

Eric Garcia: Yeah. I mean, I think that it was like, it was, again, that was one of those things where I felt like, okay, if I can’t. If you, you know, I am a boring cisgender heterosexual male, you know? But I know that there are plenty of autistic people who’ve been excluded from the conversation about autism. There are a lot of women who’ve been excluded. As a Latino male, I know a lot of people of color have been excluded. I know a lot of Asian Americans and a lot of Black people and a lot of Latinos and a lot of people who English is a second language have been excluded. A lot of people who are from immigrant families, even if they speak English as their first language. And the same way, I know a lot of people within the LGBTQ community have been excluded and I think it was really important, I think if I were to, if there was one kind of thing that I wanted to do is I wanted to say that our experiences and our, our, our kind of framing of autism has left a lot of people out of the frame.

So what I wanted to do is that I’ve wanted to grow that frame out to show the fuller tapestry. So like, I mean, if you look at your window, you’re only going to see a little bit of what’s going on in your neighborhood, only so much. So I think what I wanted to do is I wanted to get a bigger window, so you could see more of what is in the frame and include more things in the frame of the window that you otherwise haven’t seen. So I think that was really important thing.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And one thing I thought was really powerful is that you also interview several non-speaking autistic people in the book. What was that process like?

Eric Garcia: Yeah. Yeah. That was really interesting because that required a lot of changing of, I had to change a lot of my attitudes about non-speaking autistic people. For a long time, I thought that they should be cured. And I thought that it might be the right thing for them to be. But then later on I realized that maybe that’s my own bias speaking. So that was something that I had, that was a bias I had to overcome.

I think the other thing that is interesting is I think that as journalists, we tend to be really skeptical of when we had to email questions for people. Because that prevents extemporaneous conversation, we feel that that prevents people from being candid, that prevents people from you, you know, we don’t like a canned kind of statement. But I think that my feeling was if I was going to overcome, if I was going to include non-speaking autistic people, I had to get over, I had to just, you know, realize that that’s the only way you’re going to include non-speaking autistic people.

And mind you, I should say that some autistic people who I spoke to, they would send me emails afterwards saying, this is the context for what they said. Because a lot of times they, with, you know, because I know that it takes a lot of time to process things. They would, or they would take a lot of time for them to process things, they would say, this is the important context. And they realize that.

And usually after after I’ve interviewed someone, particularly someone in power or a member of Congress, people like that, I’m “like, nope, screw you, our interview’s over, you know you know, you’re doing this to make yourself look better.” Whereas I think it was really important, conversely, that recognizing that a lot of times autistic people, the process of being interviewed is such a sensory overwhelming experience that it’s important to recognize that some people, it might behoove them to give them that chance to later contextualize things or to include their, include their thoughts afterward, after we had that kind of interview.

Because I think I always kind of worry that like, if you get these questions, because like the interview is a very sacred setting for me. It’s a chance where after you’ve built enough trust and after you’ve built the right context, you set the setting where you and the interviewee are on equal footing. And it’s a really important thing. I, and I, and I don’t, I don’t you know, tamper with what, with quotes. That’s just not something I do. You know, like to me it’s sacred. It is like, you know, it’s like the red words in the Bible, you know, like you just lose you just like, they’re that sacred and you shouldn’t tamper with them.

And that required me getting over some of my own biases and my own hangups about that. So that, that, that was, that took work on my end too. I think that, I think that it’s really important to recognize. I think I really want to say is that this was as much a learning experience for me and I had to grow and I had to change through writing this book.

I don’t come at this as someone who was an authority, you know, from the head of Zeus you know, I, you know, I was, I didn’t come out fully formed. I had to learn and I had to shed my own, I had to shed my own biases that I have, and I had to shed my all preconceived notions. I had to do this. This is as much of an experience that changed me as much as it changed, as much as I hope to change people’s minds.

So I think one of the things that I, that I really insist on people, and I say, because a lot of, a lot of my friends, a lot of my neurotypical friends, they say, you know, they asked me, like people who I care about have said like, you know, “I would never want to disrespect autistic people or disabled people,” or like “what’s the right thing?” Or “I’m worried that I’m going to get this wrong.” And I think what I say is like, “look, you’re going to get stuff wrong. You are going to say the wrong thing. You are going to offend someone. You are going to slip up because this is a really complicated thing.”

This is a thing that we’ve not been conditioned to understand autism or disability. So it requires a complete rewiring of how you see the human body and the human mind. So inevitably, if you’ve gone 20, 30 years. I’m 31. So if you’ve gone 30 years without thinking about that, you’re inevitably going to mess up. So what I want to say to people is that, like, it took me a lot of learning and unlearning, and I do this, I wrote a whole book about it. So give yourself that charity. Also, I think that the disability community and autistic people as a whole recognize that when you make mistakes, if you come at it sincerely, and if you listen when people, so when autistic people are to say, look, and we’ll say, “look, that’s not the right way to say this. That’s not the right thing to do, or this is actually a bad idea. Or maybe, you know, maybe you can listen to us more or things like that,” that you come at it and you take that criticism, and you try and learn from it and you try to grow from it. You don’t, you don’t push back on it. That I think is the better way to go about it than worrying that you’re going to say something wrong ever. Because you’re gonna say something wrong.

I said a lot of the wrong things. And I think some of that, that, that cost me a few interviews, which is to say that like, people had read my past work and they didn’t like what I had written. And these were people who I wanted to interview, who I thought they were the right people to interview, but they were like, “no, you said these things in the past and I’m not interested.” I, that that’s well within their right. You know? I messed up and, you know, that cost me. But I think at the same respect, there are two ways to go, is like to say, “oh, well, they didn’t understand what I was trying to do. Screw ’em” or I can say, “you know, yeah, that sucks. I messed up. But I can do better. I want to do better. How can I do better?”

And you know, one of the things, when this book came out what happened is Jay Edidin, I believe is how you pronounce his name, he reviewed my book for the Boston Globe and he said that I got some things, I didn’t word some things correctly when writing about the LGBTQ+ community. And that was really like, and I remember thinking, man, that sucks. Because I worked hard. I wanted to include LGBTQ+ people in my book and include their voices and things like that. And I was like, man, that really sucks because I worked really hard at that. But you know, I also recognize that that’s not my community. And I had to recognize that like, you know, Jay is from that community. But just like how I want neurotypical people to understand what autistic people have to say, I have to take that as a, I have to take that and I have to say, what can I do different? You know, I had to sit with that. And I, I messaged him after and I said, look, I loved your review. I thought you got it right. And I actually agree with your criticisms. And then I, you know, and I said, I want to do better. And hopefully I do better. And I, hopefully I can be mature enough to say, yeah, you know like when people ask me about that, if anybody in the LGBTQ+ community ever asks me about it, I hope I could say, you know, my response. And they say like, “you know, you got some things wrong.” It’s like, I can say, “yeah. You know, I got some stuff wrong. Yeah. That was my mistake. Yeah. I’m sorry.” You know? But you know, rather than saying, “don’t you see how much I was trying to do stuff for you, didn’t you see?” Rather than I can say, “look, I was trying to do something right. I messed up, but I want to do right. And hopefully like, as a journalist can you help me do better, you know? So, cause I want to do better.”

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, absolutely. I feel like it’s part of that whole wider conversation about even allyship, which is just come really to the forefront in the past few years, is that people, allies are scared to get things wrong when it’s like, no, you will get things wrong. Probably multiple times. It’s a learning process. It takes a long time.

Eric Garcia: Yeah. Yeah. You know it was interesting was midway through writing this book, one of the people who I interviewed at length came out as non binary and like, what was interesting was that I cited their book when they were still presenting as their assigned gender. Here I am thinking to myself. And then I guess it gets to, like, what I did is I was just like, okay, what do I do? We had already conducted our interview. So like I said, like, so what did I do? I just emailed. I was just like, “what do I do? Because when we spoke, you know, you, you know, you were going by your old name, your dead name. And then, then, then that, like, you know, I cite your book and I was like, what do I do with end notes?”

They’re like, okay. They’re like, “just use my name now.” And they were like, and then we worked out a system that I was just like, okay. Oh, okay. Yeah. But like, it was one of those things where it was just like, I knew that that was going to be like, that was just like, It was like, oh, this is a really, this is not something I, because I just didn’t know a lot of non-binary people before then. So I got, I was just like, okay, how do I go about this? And how do I do it in a way, because, A, I want to cite their book, give them the credit, but also, you know, not misname them, you know. And then also like, how do I give that proper context and things like that?

So I think that that’s one of those things that inevitably you’re gonna, I got things wrong in the process, but then like, you know, I, I would’ve rather have gotten things wrong in the researching and learning phase then to have had the book on shelves and realize I got something wrong. You know, I’m more than willing to sacrifice a little bit of my dignity if it means getting something right.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And sometimes the easiest way to, to address that is to just ask the person.

Eric Garcia: Yeah, absolutely. Yeah, exactly. Yeah. Like if you’re ever in doubt, you should probably just ask.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. Like even, you know, I’m still learning a lot about autism. Like I was just diagnosed a couple of months ago, but I’ve maybe been trying to study and be part of the community online for about a year.

And even the basic things, things that seem like they should be basic, like identity first language versus person first language. Like I still tend to use autistic, but I, but I talked to autistic people who use person first language about themselves, but if that’s what they want to do. It’s their individual choice. But then I don’t know.

Eric Garcia: One of the things I noticed was that like a lot of autistic people, or people who are autistic, people with autism who are older, who like are not from my generation, who are from Gen X or Boomers, prefer person first language. They prefer being called a person with autism. Whereas a lot of Millennials and Gen Z prefer identity first, because they they say no, that this is a part of my identity. And that was one of those things where I was like, that might just be an age divide thing. That might be a contextual thing. And it’s like, okay, you got to just listen. You got to take, take, you have to take people seriously, you know, take them seriously and literally,

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, absolutely. So, yeah, I mean, I just feel like there’s so much misleading information sort of out there about autism. Some of the things that we talked about earlier about who’s got the influence and got the microphone half the time, that people with the biggest platforms don’t usually have the greatest information. So besides reading your book,

Eric Garcia: And they don’t oftentimes have the best intentions.

Carolyn Kiel: Exactly. Yeah. There’s that too as well. So yeah, I mean, but besides reading, reading your book, obviously everyone should go and read your book. How can the public get accurate and trustworthy information about autism? Like where should they go to?

Eric Garcia: I think that’s, I think that really, I think that there are a lot, I think that there’s a lot of really important things out there. The Autistic Self Advocacy Network’s a really important organization. Groups like, you know, websites, like the Thinking Person’s Guide to Autism is fabulous. Books like Sincerely Your Autistic Child, which is a book that I’m reading right now. It’s put together by the Autistic Women and Nonbinary Network. It’s a fantastic book that really is kind of a good introduction to this stuff.

I think that, but then also I think, you know, weirdly enough, you know, as, as much of a cesspool as it is, social media has been fantastic for autistic people in some ways. Because I think for non-speaking autistic people it was the first way that they, it was, it was really in some ways the first time that people can take them seriously and take them literally, you know, cause they have, they’re able to, because it’s a type-based medium. Things like Twitter and Facebook can be good. They can also be terrible. TikTok could be really bad for autistic people, but it can also be great. Hashtags like #ActuallyAutistic or #AskingAutistics are, are, are fantastic. Like if you want to ask autistic people a question, like ask at the hashtag #AskingAutistics is fantastic. I used it regularly. You know, if you’re new to the community, you’re new to being autistic, using like #ActuallyAutistic is really helpful. So, you know there, there are ways and there are means of doing it. And I think it’s constantly seeking out those voices and it’s always seeking out.

It requires work. I’m not gonna lie. It requires work because I think that the people with the biggest microphones, you know, they get priority when you search stuff on Google, when you search stuff on Facebook or Twitter or whatever, it’s like, it requires a little bit more work, but it’s also much more rewarding. You know, it’s the equivalent of making homemade chocolate chip cookies versus buying something at the grocery store. So.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, no, absolutely. Yeah. And social media has just been a great place to, as you said, to learn and hear directly from autistic people who for so long really didn’t have a, an easy way to, you know, not just voice themselves publicly, but to organize into groups. And I feel like with the rise of social media, so many people I talked to who were younger than even people who are younger than me, talk about not really, like feeling like they were the only one going through what they had, like for like the only autistic person, the only person, you know, with Tourette syndrome until they realize, oh, no, there’s actually tons of other people. There was no other way before social to get together.

Eric Garcia: Yeah because I think that what happened is like, if you are, if you are in Nebraska and you’re autistic, and it takes a long time, and I say this because I have a friend who her daughter lives in Nebraska, and they’re autistic. You know, if you live in a rural area and there just, isn’t a lot of rural healthcare there, isn’t a rural hospital. There aren’t a lot of, there isn’t a lot of psychiatric care in the, you know, the area that you’re living in. It might be really hard to see other disabled people, other people with disabilities or other autistic people in your community. And then, you know, conversely, if you are you know, but like being in social media, you can and Twitter TikTok something like that, somebody in Nebraska can connect with somebody who lives in Queens.

You know? The fact that you and I are talking over Zoom is, is, is, you know, proof positive of that. So like, on one hand it can be. It can be just toxic because it allows people with really bad intentions to, you know, have the same footing as people like yourself and myself. On the other hand, it elevate the voices of autistic people in a way that I don’t think they otherwise would have been elevated.

I think a perfect example of that is you, you see it just this past week when after Rochelle Walensky, the CDC Director said, you know, a lot of the deaths of people with COVID and Omicron are people who had, you know, four or more co-morbidities beforehand. I don’t think that the pushback, tomorrow she’s going to be meeting with the AAPD, the American Association of People with Disabilities. I don’t think it would have, weirdly enough, A because of the pandemic, but B, if it was just people protesting in front of the CDC in Atlanta, I don’t think it would have had the same kind of effect. But because you had people all over the country and by virtue of, because of the disability rights movement, because not everybody can take a flight, not every, some of them, their wheelchairs might get destroyed if they take a flight, you know you know, or some people can’t, you know, make the trek or the commute down, but you have these people from it was started up, you know, the, you know, The hashtags that were used were started by someone in Pittsburgh, Imani Barbarin. And you know, and it was something that was used by people in Washington and the DMV area. It was used by people in California and things like that. It created this critical mass that I don’t think even a street protest in front of the CDC headquarters in Atlanta would have had.

Carolyn Kiel: Absolutely. It really brings a lot of attention and it’s also a sustained attention. So a protest is just for a couple of hours. This is like weeks, and days and weeks.

Eric Garcia: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, I think the other example of that is you know, last year when seeyah put out her dumpster fire of a movie, music. You know, I don’t think if a bunch of autistic people went in front of a studio in Hollywood, I think oddly enough, because it was going on during the pandemic, it was released like during, like, before there was a vaccine and things like that. Like you had a lot of autistic people who were just in their homes and they saw this just like garbage movie was coming out. It created that sustained attention and it created that kind of momentum and snowball effect. That in a way it became something that Hollywood couldn’t ignore because it was being pushed on Twitter so much. It was being pushed on TikTok so much, to the extent that seeyah deleted her Twitter account. So I think that was really you know, like I always say that I was like, you know, in the beginning of 2021, you know, two obnoxious people who insulted people on Twitter are no longer on Twitter. One of them was, you know, a celebrity who had too much of a high of an opinion of themselves. And the other one was the President of United States,

You know, that wouldn’t have existed otherwise, I don’t think. Because I think the, the, the pushback was so strong and it was so sustained. It was so consistent. That when you got to the extent that when even Tina Fey made fun of it at the Golden Globes last year, that was like, one yeah, it was funny, but it was also like in a weird way. It was like, I remember thinking to myself, like we won. Like autistic people won. Because otherwise, that movie was nominated for a Golden Globe, but if it hadn’t been for that sustained pushback, it probably could have won, you know. It probably could have gotten it. But because autistic people said this movie is trash, that it shaped the conversation. I think that’s really important.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. Yeah, absolutely. Definitely. So yeah, at the beginning of the interview you were talking about, you know, when you were just starting out and starting to write about autism and how originally you didn’t really want to be the autism journalist. But essentially you, you know, you write about plenty of other things obviously, but you are like a key source and working on a lot of those stories. So how has that been now? There’s been a couple of years since you’ve been researching the book and now the book’s out. Is it, how does it feel?

Eric Garcia: You know, on one hand it’s great. You know, I think it’s cool that like, you know, there’s just something that I have a lot of authority on and it’s something that like, and it’s something I care about deeply. It’s not something I can always do stuff for, you know, because I have a day job, but like, it’s one of those things that I can do, you know, on top of my job at the Independent, I’m a columnist at MSNBC. So I’m able to write about that, you know, for my regular column for MSNBC. So that’s one thing, but I think the other thing that’s great is that you’re seeing more autistic journalists as a whole. Like, I mean, I think when I was starting out, I was like, me and Sara Luterman covering this stuff and now there’s people like Zack Budryk covering it. There’s Emily Watkins, I believe that’s her name and who lives in New England. You know, there there’s a lot of other autistic people who are working in media that otherwise weren’t working in media at the time when I was starting.

And so it’s one of those things where like, you know, it’s no longer just me, Sara Luterman and Dylan Matthews over at Vox. There’s like multiple people. And that is, you know, there’s Brady Gerber who writes for Vulture a lot, writes about pop culture. So it’s, it’s, it’s great in a lot of ways that we have a more sustained and more spread out kind of media reporters. Because that, that means that like there’s no longer this burden to for one person or two people to shoulder, you know. Like I was on NPR last year. I was on 1A with Sara Luterman. And it was great because it was like, you know, there was like one host, there’s the host of 1A. And then there’s Steve Silberman who was neurotypical and then, you know, Sara and I, you know, we were all on equal footing. You know, obviously the host has a little bit more power. But like, you know but, but that in and of itself is great because it’s like, there’s now more people doing more stuff and it’s no longer, no longer falls on one person anymore.

Carolyn Kiel: That’s great. And it’s always,

Eric Garcia: Or two people, or whatever.

Carolyn Kiel: And it’s always great to see autistic people just represented in different, different types of careers. It’s not all just STEM. Honestly, so many of my friends and people I’ve talked to are, who are autistic, are also writers and creatives and artists. And it’s like, I kind of forgot about the whole STEM stereotype, because all my friends are creatives.

Eric Garcia: Most of my friends who are autistic are not in STEM. They’re painters or they’re lawyers or they’re lobbyists. Yes. I mean, that’s partially just because I live in Washington and a lot of the autistic people I know, like a lot of other people– surprise! — work in politics or advocacy or nonprofit work or whatever. But, you know, I know a lot of autistic people, you know, across the country who are grad students studying, you know, who work in English and communication, or they are, you know, a lot of students, when I went to the university, when I went to Marshall University, they were studying like environmental, who are autistic or say like environmental science, you know. Like it, and that’s great too. It’s like, it’s not just, you know, it’s not just computer coders.

It’s people who like live in Appalachia and want to improve their region. You know, I think the example is someone like Greta Thurnberg, you know, she’s not doing disability advocacy, she’s doing environmental advocacy. And that she talks about how being autistic is a driver of her advocacy, but it’s not the thing that she’s advocating for. It’s not, it’s, it’s part of her identity, the driver of her identity, but it’s not the thing that she’s advocating for and it shows how autistic people can contribute to other sectors. So that in of itself, y ou know, my friend, Zack Budryk, you know, he works at The Hill, he writes about energy policy. He doesn’t really write about disability policy that much, but, you know. So that that’s important, you know, like having other people in different sectors so that all those things are important.

So,

Carolyn Kiel: absolutely well, that’s absolutely awesome. So, yeah, Eric, thank you so much for being on my show. Where can people get your book, We’re Not Broken? Where should they go to get that?

Eric Garcia: We’re Not Broken, Changing the Autism Conversation. You can get it wherever fine books are sold, you can get it on. So that means you can buy at your local bookshop.

If not, you can always ask for it. You could get it at your library. You know, that’s all, you could request it out of your library for it to be there. You can also get it on bookshop dot org, you can get it on indie bound. You can buy it directly from Harper Collins, which is my publisher. You can buy on Amazon though. I really wouldn’t like it if you got it on Amazon, but I understand if you like Amazon you can get it. You get it through, get it through Barnes and Noble, Target. Wherever, wherever you buy your books, you can order it online. And and you know, yeah.

If you, you know, I really appreciate you welcoming me on the show. I really appreciate talking with you about this. And and you know, I hope people after this go out and buy the book and if they have any questions, ask me. So, you know.

Carolyn Kiel: That’s wonderful.

Eric Garcia: You asked me if you want to be on the podcast. And I was like, okay, cool.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, I know, it was fantastic. I really enjoyed talking with you, Eric, and absolutely enjoyed the book and yeah, everybody go out, buy We’re Not Broken. It’s just a really great way to get introduced to the whole conversation about autism and yeah, really expand your mind. I learned so much from it and I know that that all my listeners will too. So, yeah. Thanks again, Eric. Really enjoyed talking to you today.

Eric Garcia: Thank you so much for having me on the show.

Carolyn Kiel: Thanks for listening to Beyond 6 Seconds. Please help me spread the word about this podcast. Share it with a friend, give it a shout out on your social media or write a review on Apple Podcasts or your favorite podcast player. You can find all of my episodes and sign up for my free newsletter at beyond6seconds.net. Until next time!