Haley Moss is the first openly autistic lawyer in Florida, a neurodiversity expert, and the author of four books that guide neurodivergent individuals through professional and personal challenges. Her latest book is “The Young Autistic Adult’s Independence Handbook.”

During this episode, you will hear Haley talk about:

- Learning she was autistic at the age of 9, and giving her first public talk about autism at age 13

- Her decision to become a lawyer

- How her latest book shares the “unwritten rules” about being an adult, along with life advice for autistic young adults

- Why interdependence and asking for help are important parts of young adulthood

- The powerful impact of advocating at the local community level

To find out more about Haley and her new book, you can find her on HaleyMoss.com, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Special offer! Beyond 6 Seconds listeners in the US or UK can save 20% off the purchase price of “The Young Autistic Adult’s Independence Handbook” and/or “A Freshman Survival Guide For College Students With Autism Spectrum Disorders” by Haley Moss. Go to jkp.com, add one or both of these books to your cart, and enter the discount code Moss20 at checkout to get 20% off those books. This discount code is valid on jkp.com until July 15th, 2022 and can be used in the US or UK only.

This month (June 2022), we’re also doing a giveaway for our US listeners! Check out the June 14, 2022 Instagram post at @beyond6seconds to learn how you could win a free copy of “The Young Autistic Adult’s Independence Handbook.”

Subscribe to the FREE Beyond 6 Seconds newsletter for early access to my latest podcast episodes!

*Disclaimer: The views, guidance, opinions, and thoughts expressed in Beyond 6 Seconds episodes are solely mine and/or those of my guests, and do not necessarily represent those of my employer or other organizations.*

The episode transcript is below.

Carolyn Kiel: Welcome to Beyond 6 Seconds, the podcast that goes beyond the six second first impression to share the extraordinary stories of neurodivergent people. I’m your host, Carolyn Kiel.

One of the most challenging times in a young person’s life can be the transition to adulthood, whether that means living away from home for the first time, graduating from school, getting their first job, or any number of things that we associate with quote unquote “adulting.” It’s a big change for most young adults – but it can be especially nerve-wracking for autistic young adults.

My guest today, Haley Moss, is an autistic woman who’s written several books for autistic children and young adults to help them with life transitions like this – including her latest book, “The Young Autistic Adult’s Independence Handbook.”

On today’s episode, Haley talks about how this book shares the unwritten rules about being an adult, along with life advice geared towards autistic young adults. She also breaks down some of the misconceptions about being a young adult, like the expectation of complete independence (when in fact, interdependence is more realistic – very few of us are completely self-sufficient in every way), as well as the importance of asking for help (and the double standard that makes many disabled and neurodivergent people afraid to ask for help).

Haley also shares her own story on this episode: How she learned she was autistic at the age of 9, her autistic pride and challenges, her first public talk at age 13 that kicked off her autistic self-advocacy, and how she decided to become a lawyer. She also has great insight on the impact we can have as advocates in our local communities – and how to get that first leadership position in a community organization.

I’ve also got something really special for you, as a listener of this episode! For a limited time, I’m partnering with Jessica Kingsley Publishers, which is Haley’s book publisher, to give away up to 3 copies of her latest book, “The Young Autistic Adult’s Independence Handbook,” as well as a special discount code you can use to purchase the book at a 20% discount. I’ll tell you all about it at the end of this episode.

And now, let’s get to my interview with Haley!

On today’s episode, I’m very excited to be speaking with Haley Moss. Haley is a lawyer, neurodiversity expert, and the author of four books that guide neurodivergent individuals through professional and personal challenges.

She’s a consultant to top corporations and nonprofits that seek her guidance in creating a diverse workplace and a sought after commentator on disability rights issues. The first openly autistic lawyer in Florida, Haley’s books include “Great Minds Think Differently: Neurodiversity for Lawyers and Other Professionals” and “The Young Autistic Adult’s Independence Handbook.” Her articles have appeared in outlets including the Washington Post, Teen Vogue and Fast Company. Haley, welcome to the podcast.

Haley Moss: Thank you so much for having me.

Carolyn Kiel: I’m really excited to learn more about your story today. You were diagnosed at a relatively young age, like the age of three. So you knew, I guess for at least part of your childhood, that you are autistic. So like, what was life like for you growing up autistic?

Haley Moss: You’re right. I did know since I was young. So my parents actually told me about being autistic when I was nine years old and nine year old me was absolutely obsessed with the Harry Potter series. So my parents compared it a lot to being like Harry Potter. That the message that they really sent home with me as a little kid, was that different was neither better nor worse. It’s just different and different could be extraordinary. So I grew up already having this understanding, this framework that this wasn’t something to be ashamed of. So that was really cool.

But, like many other young autistic people, I did feel that something was different to an extent. Like, I didn’t think that I was weird. I feel like that’s the wrong thing to say, because I didn’t think that I was weird. I thought that I was really cool and other people just didn’t get it. So I felt kind of alone in the fact that I didn’t really know a lot of other autistic people until I was a teenager. And then I didn’t really know a lot of autistic people again until after in my adult life.

What I always felt was that I’m on to something and I’m still trying to figure out what the neurotypical people are doing. It’s a lot like being in an immersion program in a way, I guess, is the best way to describe it, is you’re trying to figure out what is this language and culture that all these people are experiencing and doing, but you don’t always know the rules of the game. So you’re trying to figure out what the rules are, kind of as you’re existing.

I feel very lucky because I did know I was autistic young. I had very high self-esteem for someone who didn’t quite always get it and didn’t understand why others, especially other girls didn’t want to hang out with me or that I wasn’t making friends in the same way that others were, that my interests were different. So I honestly don’t feel like my childhood was exceptional in any way, shape or form. Other than that, I was just very happy. And I feel like that’s something that I guess, based on how a lot of other autistic people described their childhoods, that it is exceptional in that. And I think a lot of it was that I did have a very accepting family.

Carolyn Kiel: That’s great. And then in school, I know you mentioned some social challenges with like making friends, especially with girls and things like that. Did you have any other challenges in school, whether it was sensory or just the way it was structured and kind of, how did that get addressed?

Haley Moss: I went to a private high school and my high school had a lot of pressure on its people. So there was all this pressure to succeed. It was very competitive, it felt like. That was really hard for me because I was just trying to survive, especially socially.

And when I think about high school, there’s one thing that really sticks out because I actually got outed as an autistic person when I was in high school, because I wasn’t very open about it with my peers. I didn’t have that policy. I kind of was a, I will tell people when they need to know. So guidance counselors, teachers, people who were important and integral in my educational life, not necessarily my friends.

So when I was in my freshman year of high school, I was doing a fundraiser with my artwork for the University of Miami’s Center for Autism Related Disabilities. They’re the ones who diagnosed me. They’ve done a lot for my family. They gave us a lot of guidance, all sorts of great stuff. And I was selling artwork to help raise money for them. And I gave a flyer about my show to my teacher. He asked me why I’m doing this and why they’re the beneficiary. And you know how it is. The story goes, I’m a terrible liar. Don’t really know what to do. And I end up basically saying, well, you know, I’m autistic.

That’s the thing that was really interesting for me. It kind of also set up the rest of my life, even though that’s probably not how I would have gone about telling people, but it didn’t create some magical culture of inclusion at my high school. It just was this moment that really seemed to make me feel comfortable with myself. And it’s like, you know, I don’t really care who knows, but it was also the thing that made high school more challenging at the same time.

So I was actually thinking back on this, cause I know at, especially at this point of the year, like when we were recording, a lot of folks are thinking about where they’re going to college. And I remember going to the college fair at my high school, and some girl comes up to me when I have my like, hands full of brochures.. And she goes, “well, you don’t have to worry about that.” And I go, “what do you mean?” And she goes, “well, you have a disability. Like colleges are gonna love that. You’re fine.” Essentially saying they’re going to pity me, and I’m going to get accepted, when really I’m working just as hard, if not harder than everyone else, because my disability does make life harder in so many ways. And I’m taking the same difficult honors and AP classes. I’m doing extracurriculars. I work at the paper, I’m doing my artwork. I’m doing all the same stuff that other people are doing, if not more. And it was really disheartening to think about. So when I think about young people, it also amazes me just the callousness and the cruelty that they can exhibit. And maybe it’s just something I wasn’t expecting.

And it’s really interesting that some of these same people are the people now that go “well, you know, you being open about your story helped me be open about something else I’m dealing with.” And I’m like, “but you also didn’t talk to me. Or you were the same person who wasn’t nice to me. This is very confusing.” And this is 10 years ago, at this point.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. It’s interesting because, everybody has a story or multiple stories about times that they were bullied, but no one remembers being the bully. And it’s like, some of y’all were bullies. Was it deleted from your memory? Or I guess their experience is different from, you know, when you’re on the receiving end it’s, you know, you remember it more so, yeah.

Haley Moss: Exactly. And I think even for me, what made that more difficult is I wasn’t bullied in the very traditional sense. Like the name calling or the kind of very obvious, you’re going to get something kicked out of you into tomorrow, but I was more often just excluded. And the people who were cruelest to me, when I look back, were the people I was friends with. Is that they’d be the ones who maybe didn’t invite you or they left you out. And then they’d be like acting all caring about it when you confront them, like, “why was I the one girl not invited to the sleepover?” And it would be like, well, you know, either their parents didn’t want to deal with it because autism seems like too much to them or they’d be like, “well, you know, we know this is really hard for you. It’s sensory, it’s this. And we just thought you wouldn’t want to go.” And it’s like, I’m a person with agency and I’m capable of deciding if I want to go hang out with you or not. So I think that’s kind of this quiet form of bullying that happens is this kind of benevolent ableism thing. And it’s something that I think we experience a lot as adults: that people are well-meaning, but they end up taking away our decision-making powers in the same breath, and they don’t recognize it as something that is harmful.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, absolutely. It’s just trying to figure out those social rules again. And sometimes they are purposely confusing. Like I couldn’t explain it, you know, logically to anyone. It can be a difficult time.

Haley Moss: And it’s ever evolving. And when I look back on when I was in high school as well, and this is why I also am especially empathetic to today’s young people, is that was when social media was kind of on this rise. So when I was in high school, it was all about Facebook. And I recognize that the people who came maybe five, 10 years before me, they didn’t have to deal with the same level of stuff with the internet.

And this generation has not only just Instagram, but they have Twitter, they have Snapchat, they have TikTok, they have this, they have that. They have a lot more than just to worry about like Facebook or what’s going on when you’re IM’ing after school.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Haley Moss: It was still, it wasn’t really like a novelty to have an iPhone or a text messaging in school back then, but it was not as prevalent when I started high school versus when I finished high school.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. I know when I was in school, I’m grateful that we didn’t have social media or like, you know, the internet was in its very basic infancy. So, cause I can’t imagine, as you said, how people, how kids these days deal with, you know, especially if you’re subject to bullying. It doesn’t stop when you leave school. It’s just like always there.

Haley Moss: And the social rules, especially with the internet and internet culture, just change even faster. That the rules are constantly shifting. So by the time you figure out that something is cool, everyone else has already moved on.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. So, you know, you found out that you were autistic at age nine. And what I find is remarkable is that you started your self-advocacy just a few years after that. I think you spoke at your first conference at age 13, so that’s amazing. How did you get that opportunity and how did you kind of make that part of your advocacy?

Haley Moss: I was someone who was raised to always give back. And the folks at CARD, actually from when I was diagnosed and because my parents were always in touch with them and stuff, they asked if I’d be interested in speaking on this panel. And the conference is in Orlando. So you have to understand the mindset of young Haley at 13 years old, that an excuse to go to Orlando means it’s an excuse to go to Disney World. So even though growing up in Florida, I’ve been to Disney World plenty of times, because that’s apparently a thing that happens. So, and that’s what we’d do for family vacations, cause my dad couldn’t get away from more than a couple of days when I was growing up. So we’d go to Disney World a lot. But an excuse to go to Disney World, and all I had to do was say a couple of words? Sure. I’m in. That was kind of how I fell into advocacy. I didn’t plan on ever doing it. I was like, okay, I’m going to give back and I’m gonna get to go to Disney World. Everything’s great.

Someone on this panel that was in the audience ends up asking how I know about my autistic identity, and that I know this and how my parents told me. And I tell them the story. And apparently it’s really captivating. And someone from publishing was in the audience. And that was how things got started essentially. And it’s been a wild ride to think that I’ve been doing this now for more than half of my life.

Carolyn Kiel: Wow. Yeah. That is really amazing. And just, you know, being up there. You know, even as a young public speaker. And then, you know, obviously now as a lawyer, like public speaking just comes with, you know, the profession and you do it all the time.

Haley Moss: I like public speaking. I know that the majority of people are terrified of it. But I am someone who genuinely has always loved it because it’s the most in control you can feel in a large social situation. That other people are listening to you. You probably have their attention. They usually don’t get up and leave and make funny faces. And there’s too many of them that you usually can’t tell if they’re doing any of those things. So for me, it’s kind of this less anxiety inducing experience then say, being at a dinner table with like five people.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Haley Moss: Because you could have three different conversations going on at once. You have to keep track of what that person’s doing and that person’s doing. And when do I talk, and when do I not talk? Like public speaking to me feels like very natural. So I was fine with it.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. Plus you can prepare for it. Like you figure out what you’re going to say. And then as you said, people listen to you. They usually don’t get up and leave or have negative reactions. So that’s great.

Haley Moss: I mean, I teach undergrads right now, and never have I had a captive audience the way that you do, when you have kids that have to show up for attendance.

Think about it like this. Like when you have teachers and stuff, or you’re in a lecture, you’re basically like a captive audience. Like you can leave, but it’s kind of frowned upon. And if you have ideas and things you want to share, you really get the opportunity to share it.

Carolyn Kiel: That’s very true. Yeah.

Haley Moss: My students are also really cool. So if my students are listening, I love you guys. You’re incredible. And thank you for listening, being part of things, the last couple of semesters.

Carolyn Kiel: Oh, that’s so awesome. So, you know, you’re now a lawyer. So how did you become interested in law? Did it start early, like in college or before that? Or how did that path come out?

Haley Moss: I had no idea I wanted to be a lawyer, if you want me to be completely honest with you. Because you have to understand what kind of young person I was. I was very shy. I did not do speech. I did not do debate. I had no interest in possibly majoring in political science. I was not your cookie cutter, this is the kid that’s going to law school. And I set that up on purpose. Cause I think we have a lot of misconceptions about who are lawyers, essentially. I was very introverted. I still am. I was pretty shy, but I like to talk to people and public speaking. If you get me to talk about something that I like, I will talk to you about it all day long.

And I thought that when I was going to college, that I was going to be a doctor. I thought the coolest thing in the world was going to be to major in psychology, become a psychiatrist and help other people with their brains and their problems. And what better way than to understand people who naturally don’t make sense to you, then to understand the human brain. I had it all figured out until about six weeks into college. And then I took chemistry and I realized I absolutely hated it. And this was not what I wanted to do. And when I got back to the drawing board, I had to think, well, what do I actually enjoy? And I like to talk, I like to write and I like to help people. And I realized lawyers have the potential to do all three of those things. So that is how I landed on becoming a lawyer, having known nothing about what lawyers actually do.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, I went to a liberal arts college, so we didn’t have like premed and pre law. And I was a psychology major myself, and I thought I would be a psychologist.

Haley Moss: Hey I still stuck with it!

Carolyn Kiel: It’s a fun, it’s a totally fun major.

Haley Moss: It was a great major. And then I ended up, when I realized I was kind of on the law school path, I ended up double majoring in criminology and law. I’m thinking like, okay, that’s a fun add on. And the tie-in with like psych and law and like jury selection. It was really cool.

Carolyn Kiel: Oh, that’s really cool. And what kind of law do you practice now?

Haley Moss: I’m currently not in practice. In my past life, I practiced in healthcare and healthcare litigation, and I also dabbled in our international law practice. So I mostly represented hospitals and I also got to work on anti-terrorism cases, which sounds extremely cool and also extremely dangerous. So. It was very cool because in when I’ve looked back on it, cause I was watching Ozark on Netflix and some of the stuff they were talking about was stuff I was familiar with from my olden days. And I was like, hey, I haven’t heard some of these terms in a while. Cool. I actually understand stuff.

Carolyn Kiel: That’s good, and you can assess how accurate it is.

Haley Moss: It’s not even that it’s accurate. It’s more stuff that I realize probably the general population in acronyms are not very familiar with I’m like, I know what this is.. Because it’s all sorts of stuff about how, you know, who like the government will do business with or things like that. Like they mentioned something about the SDN list, for like specially designated nationals, essentially that there’s people that the US government won’t do business with. They’ll freeze their assets, things like that. And I’m thinking, does the regular person know what they’re talking about? Or is this just stuff I know, because I used to practice in this very specific thing?

Carolyn Kiel: That is interesting to see like echoes of your past, your past life, past careers and experiences through TV and things like that. That is interesting.

Haley Moss: It’s always interesting because even though I feel like with what I do now, because I mostly do consulting and I do events, I do all sorts of other stuff too, that going to law school and having a legal background, I use it more than you would think. That it’s more, I don’t think it’s so much what you do with it so much as it’s the skill set. That’s what matters. Yeah. If you get really good at talking to people and you try to figure out how they think and that it changes how you think and the questions that you might ask of other people and other things. It makes me very curious. It’s a lot like being a journalist.

Carolyn Kiel: Oh, yeah. And that combined with psychology. Cause that’s another major that like, you can use that anywhere. Like those basic principles translate almost any career.

Haley Moss: A lot of these things have parallels. Even when I wasn’t law school, I think it was one of the few psych majors I knew. Most people came from political science and having a psychology background helped when you got to the more practical things. So in school, I don’t feel like it really did as much, but when you got to actually interact with people, you had a little bit of a leg up.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, no, absolutely. And then, you know, in addition to speaking, which I know you enjoy, you’re also a writer. And you’ve written four books focused on autistic children. You have one about middle school and high school and then college, and then your most recent one is about young adulthood. Once you’re in college or you’re just graduating and you’re going out on your own and trying to kind of figure out your own independence and your own life.

Haley Moss: Because nobody knows how to be an adult.

Carolyn Kiel: That’s why, when I was reading it. I’m like, you know, there’s a lot of really great basic advice that like no one tells you.

Haley Moss: That’s what I was trying to go for because I, when I was going to college, I felt like I failed at being an adult. And then I still feel like I fail at being an adult quite a bit.

A lot of it is that there’s just things we don’t think about, or things that we think are just part of existing that everybody does. And we just don’t get taught and someone’s like hiding the eight ball.

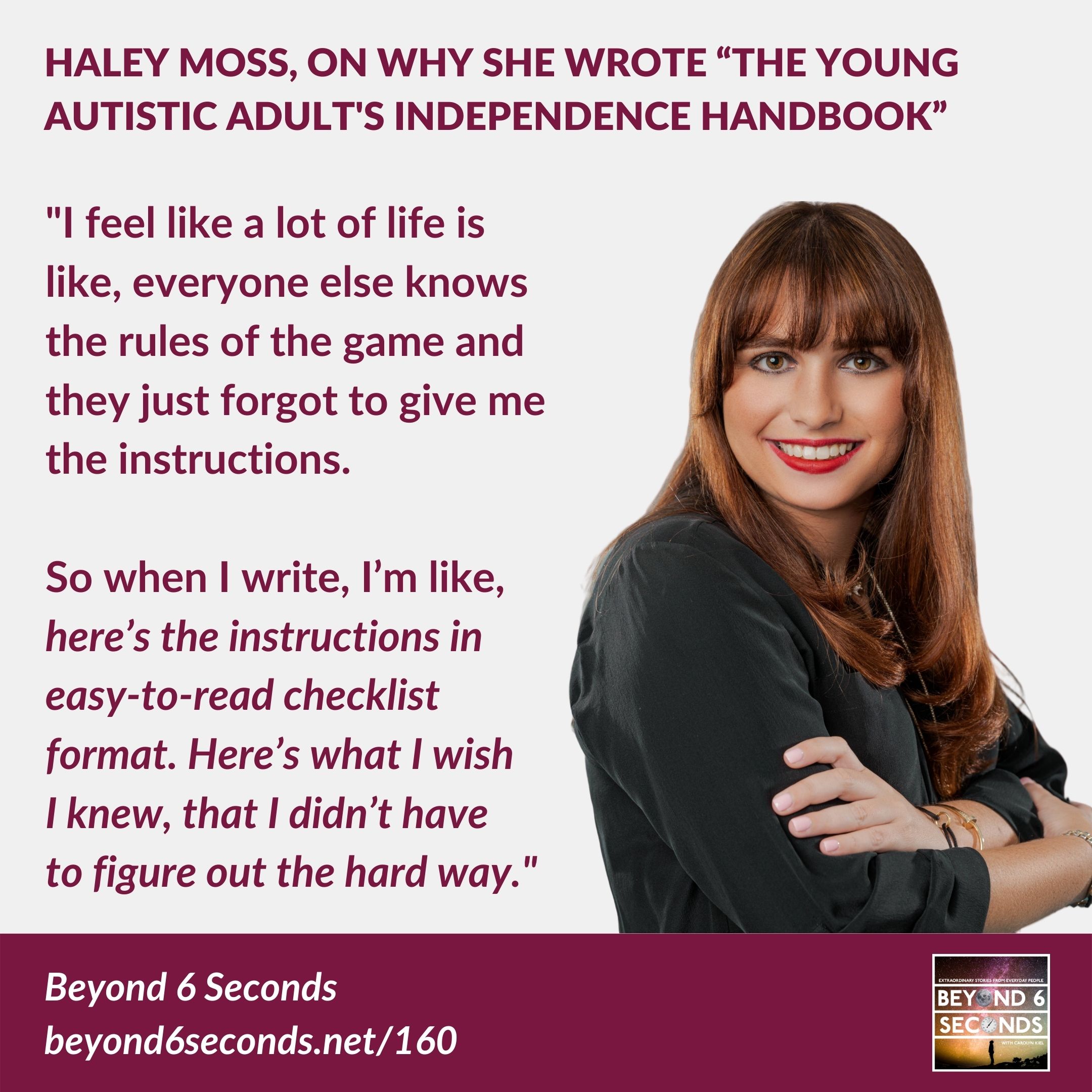

I feel like a lot of life is that everybody else knows the rules of the game and they just forgot to give you the instructions and you’re trying to figure it out. So when I write, I’m like, here’s the instructions in easy to read checklist everything format, because here’s what I wish that I knew, and I didn’t have to figure out the hard way. And that’s kind of my approach to writing things like that, is, how do I make this better?

And also, independence is almost like this myth we’ve been sold. And I think that’s something that I’ve noticed the older I get, because when I was a young person transitioning to adulthood, I thought independence meant I had to do everything by myself. I genuinely thought it meant no assistance. I thought that it meant that I wouldn’t have to ask my parents things. I didn’t think it would mean that I’d be calling them three times a day asking how to do things. I didn’t realize it now in some places, and some pieces of my friend circle, I’m now the responsible adult friend, which I think is ridiculous, because I don’t think I know everything.

It’s funny. Actually, I had a friend text me earlier today who’s mailing a Mother’s Day card and asked me how many stamps that requires and how to get stamps that aren’t from the post office. And I was like, oh wow. I actually had these adult answers now.

Carolyn Kiel: That’s in your book! Like that, I remember that. You can get them at the supermarket.

Haley Moss: That’s why I was telling my friend. I’m like, you can get them at the supermarket counter that sells the lotto tickets and cigarettes. Because I don’t know the name of the counter off the top of my head, but I’m like, I know at our specific grocery stores, that’s the one. Oh, I’m like, oh no. Now I’m the adult friend! Am I the adult friend because I’ve been alive a while now? Or am I the adult friend because I’ve written about this and researched all this extensively, in true autistic fashion?

So, and that’s what I realized that that’s what independence is, is having the skillset to be able to advocate for yourself, or even be like my friend who just said, “Hey, I don’t know how to do this” instead of, “oh my gosh, I suck at being an adult. I’m never going to mail a Mother’s Day card.” That adult is going, “I’m going to mail a Mother’s Day card, and I don’t know where to get stamps.” Instead of just thinking “I’m a failure. And I did nothing because I don’t know how to get the stamp.”

This happened like less than an hour ago, which is why it’s on the top of my brain. And the more I think about it, the more I’m like, yeah, that makes sense. And I think a lot of non-disabled adults don’t have that issue, or neurotypical adults, where they’re not afraid to ask those types of questions at the risk of possibly sounding silly. Well, if we ask them, it’s almost seen as well, you’re not independent enough. I think there’s a huge double standard. And I wanted to kind of break that down. Especially when I was in college and academically. It’s funny because I would always advise in books and stuff, like go ask your professors for help. And I was always ashamed to ask for help. Cause I thought it meant they’d think I’m stupid and that not needing help meant that I would be a more successful student. And I didn’t realize when I asked for help, that’s how I made the relationships. That’s how I got to work in a research lab is because that was the only way I ever got to see my professor face to face. Or that, that was how I’m going to do better next time is realizing this is what they’re looking for. This is what they need. Not that you need to just know how to suddenly fly perfectly every single time.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. I think for a lot of autistic people, or even just speaking for myself as an autistic person and other neurodivergent people, disabled people as well, there is that fear of asking for help.

One, because of that double standard that you just talked about and two, because sometimes it’s just not viewed in the same way as it is with neurotypicals.

Haley Moss: And there’s also so much internalized ableism that I think we deal with too. That, how many times have you asked for help and you feel like you’re bothering someone? Or you’re, or you’re asking for too much? And really you’re just trying to survive, but I always feel kind of guilty and I’m realizing you are not too much for asking. What’s the worst that’ll happen? Someone will say no?

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Haley Moss: And then what, you ask someone else? Or worse comes worse, I know so many people do this as well, you just end up asking Google. If you really don’t know it. That was actually a question that somebody asked me the other day, that was probably one of the best autistic questions ever: when do I ask my parents versus when do I ask Google? Oh, it’s like, depends on your relationship with your parents, is the lawyer answer.

Carolyn Kiel: That’s true.

Haley Moss: Well, sometimes I’m going to ask Google and if I can’t get a straight answer or something Google won’t know, then I’ll ask my parents or somebody else.

Like, like for instance, my parents help me clean my apartment every couple of weeks. And sometimes my mom puts things in a different cabinet. Google will not know where she puts the thing. That’s when I have to go, Mom, where did you put the thing?

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Haley Moss: But a lot of the problems I do try to research first and then if I don’t have a definitive answer or I just want a human’s input on it, that’s not, you know, the internet or something from many, many anecdotes, then I’ll ask other people. It really just depends. I like to make sure I get it right.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And there’s a lot of that information now is out on Google or YouTube. There’s a video on almost like how to, just about anything, I guess. So yeah, there’s a lot out there. And you, you mentioned that sort of myth of independence. And I think, especially in like in the United States and American culture, there’s this sort of, you know, ideal of being the independent person. But you, you really talk about pretty early in the book, this concept of independence versus interdependence, and how like all of us, every single person is interdependent, whether or not they want to admit it. But like, we all need to rely on other people to survive.

And I think if you’re disabled or autistic or neurodivergent, a lot of times that’s kind of like an extra stigma. Maybe it’s that internalized ableism or other pressures where, you know, you want to prove that you can do everything yourself, or that should be an ideal, but that’s really not an ideal for anyone. So I think it’s really great that you bring that out early in the book and then talk about like, This is how we’re supposed to live is interdependent on each other. And here are some examples of that.

Haley Moss: Exactly. And I think it’s really interesting when we talk about it as a cultural thing. Because there are a lot more collectivist cultures that it’s like, it’s okay, the rest of the community will take care of you. While I think a lot of westernized cultures for the most part don’t do that. But when I was thinking a lot in researching interdependence as a concept, a lot of the work that I came across was rooted in disability justice and the work of folks like Mia Mingus. And when I read Mia Mingus’ work, something that she says is that: let us remember how interdependent our lives are. Not only when it’s convenient, but every single day. And when I read that, it really stuck with me. And I think about, yeah, our lives are.

We have no problem when something like our air conditioner breaks. Sorry, I live in Florida. I have to say it, my AC breaks more than I’d like to admit. But I am not someone who can fix it and that’s okay. Nor should I be. And think about how many of us I know in the United States, I know a couple of weeks ago was tax day. How many of us might need the help of a tax service or an accountant or someone else that knows what they’re doing? That that is ways that we’re interdependent. We don’t just do everything as lone wolves our entire lives. And that everything is kind of a give and take that each of us has different things to give to the world and offer the world. And others have things that they take and borrow from other members of the community. That’s just life.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And things just change over time. Like those sort of core skills that were important 20 years ago. Going back to your example about where to find stamps. Like, I feel like that’s something maybe more people have known like years ago, but now like it’s so rare that you have to mail something it’s like, of course people wouldn’t necessarily know that anymore. So well, even skills, they just change over time, what you’re expected to know.

Haley Moss: Exactly. Exactly. And I think about that with even things like writing checks.

Carolyn Kiel: Yes.

Haley Moss: Which is something that I would have probably given a visual because I’m pretty sure I have to look up how to write a check every single time I do it. Cause based on how many checks I’ve written in my life, I can count them on both my hands. So meanwhile, I’m pretty sure my parents have written countless checks.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Haley Moss: Because a lot of us, they get printed. We have Venmo, we have Zelle, we have electronic payment, we have so many other options. So some of these things that we have to do that seem or feel antiquated are confusing.

Carolyn Kiel: And I remember learning when I was younger, how to write a check, like that was taught to me. It’s not like just something that I magically knew, so it wouldn’t expect other people to just know it.

Haley Moss: Exactly. And we just assume, I think, especially as a generational divide, we just assume these things happen. So I think there is a generational component to it too, because especially when we think of like older autistic folk who might’ve been taught that, and then the younger ones aren’t. And then they think, oh my gosh, I’m inadequate. Instead of, you know, this just doesn’t happen at the same rates that it did when our parents and siblings and others might’ve been growing up.

I find that really interesting to think about too, but it is a skill that I do find myself every time I have to do it, I go, wait, am I doing this right? And I feel kind of embarrassed in my own head, even though I won’t usually admit that too loud, but here I go, just admitting it.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. I mean, there’s a lot of things like that, especially if it’s something that you don’t do that often, you know.

Haley Moss: And you want to make sure you get it right.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. Yeah.

Haley Moss: You feel embarrassed if you don’t.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Haley Moss: Especially when you’re say paying a bill or depositing money into something. Then yeah, you have to know those things. There’s a lot of things that I wish were just taught in schools, and I feel like that’s where independence I think really does fail autistic people who don’t learn the rules of the game of life so quickly or where it’s assumed we just know it.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. So you have a lot of that information in your latest book. So it’s called The Young Autistic Adult’s Independence Handbook. So, I mean, what kind of feedback have you gotten from your readers on that book?

Haley Moss: I think people are happy to have answers to things. And personally, for me with writing it, I was really grateful for the wonderful folks who are willing to talk to me. So people like Dr. Shea, who spoke to me about food, for instance, and Dr. Shea taught me how to try new things. That was very cool. I was still kind of nervous to do it, and I’m still kind of scared to try some of the stuff she taught me. Mostly because trying new food is one of these big anxieties I have in life because I don’t like change, but I feel comfortable knowing that she gave me some strategies I could check out.

Like, I think that was the coolest thing was the people I got to talk to who gave me some insight into things. And Karla, who taught me about grief, because I don’t know how to do grief. And I don’t know how to do grief with other people’s grief, and that they all look different. That it’s hard when you lose somebody, or a pet or something that you love and care about. And having someone say, Hey, this might be amplified, or your autistic traits might be amplified or, or you might not react in the way that we think and it’s taboo. Like that stuff I think it was really cool.

But as far as readers, I just hope that people feel less alone. That’s always what I want. I started writing when, and when I was a young autistic person, I just wanted to be able to help somebody. I still feel like that’s what I want to do. And I think when you’re a young person, especially, it’s very easy to think that you’re the only one who struggles with X. Whatever that little thing is. Not just autism as a whole type thing, because I don’t think it’s all just struggling with autism, because so much of us have joy, we’re thriving and life is great, but there’s all these little traits or little tiny quirks or things that we think are just “us” problems, that you’re the only person in the world who does this thing. And I think realizing maybe you’re not the only person in the world who does this thing is pretty helpful. Like, not all of us are good at executive function. Not all of us have clean houses. Not all of us go to the grocery store and know exactly what to do, and don’t get overwhelmed, and what happens when your favorite brand of yogurt is sold out? And I feel like those are experiences that most of us don’t get in a book or we don’t feel represented in. So I’m like, I hope that I can help somebody. Or if they realize that their favorite brands aren’t there, that there’s an alternative or they just don’t buy it. And that’s okay too.

I just want people to feel loved. And what I really wanted to do as well, and I, this is the thing that people seem pretty excited about, was give a little bit of a roadmap to get involved in your community as well, because so many of us talk about making change. We become content creators. We do all sorts of different stuff. We talk to our friends, but we don’t know how to sometimes make it super tangible real-world action as well. So trying to give a little bit in that direction felt really awesome.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And that was one of the points that really stood out to me as I was reading your book was around advocacy. And you saying, you know, really look to your local community for self-advocacy or or doing advocacy because there are opportunities there. Not just looking online, because online is intense. Like there’s a lot.

Haley Moss: Exactly, and it doesn’t always feel very representative of what is happening in your community.

Carolyn Kiel: Right.

Haley Moss: Like, I know it’s very easy to say certain things about certain groups in certain like policies and stuff, but you will notice if those change in your local community versus if they change on the internet, is always what I like to say. Like, you will feel the impact of your local advocacy organizations.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Haley Moss: Or if they’re not funding services and then there’s a bunch of families that aren’t able to get services or have access to therapy or anything for that matter. So I always think the local level is really, or statewide level depending on where you live. So I know in Florida, the thing that I’ve been trying to get more involved with is we have a coalition to get guardianship reform, and that is something I know affects a lot of young people on the spectrum and others with intellectual and developmental disabilities, and getting reform would be fantastic. And sometimes it feels like the Internet’s not the ones who are going to get that accomplished because if they were, I think it would have already happened thanks to Britney Spears, to be quite honest. So that’s why there has to be pressure from those of us in our communities, to try to get things done.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And you’ve been a lot of times you’re in a situation where you’re like the only autistic person on a board or in a group. And I would imagine, I’m sure your psychology and law background help with this, but you have to be pretty researched and persuasive when you’re sharing what’s important about, you know, the thing that you’re bringing up or the services people need or whatever it is.

Haley Moss: Yeah. And sometimes you have to be the loudest one, which is really frustrating because you don’t want to be. Sometimes you just want to listen. And a lot of the times I do want to listen because I want to understand the dynamic before I speak up.

But something I’ve been trying to do better at, is if I am sometimes the only autistic or disabled person in the room, I always challenge myself to get two other people. I try to get two more people involved, so then there’s three of you, or two of you. But you need to get at least somebody that, that way it’s not tokenization and that there’s actual accountability.

So like when I got onto the board at UM CARD, I think there was maybe two of us and I didn’t meet the other autistic person on the board. And now I think there’s four. So that’s been one new person a year on average or so, and I think we’re trying to keep growing that. And those of us who are the self-advocate squad, as we joke, that we even have our own separate group texts to say, what are we bringing up at the meeting? And that we’ll make sure to back each other up if possible, so then our voice as a collective is heard. Because sometimes it’s very easy if it’s one dissenter to get ignored, but if there’s three or four of you, it’s a little bit harder to ignore you on a group of say 12 or 13, for instance.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, well, that’s very true. And then, you know, you’ve served on different boards and been part of different community groups and governance groups. How do you kind of get your foot in the door? Because I would imagine once you’re in one opportunity that maybe other opportunities present themselves down the line, but how do you kind of get in, like that first one or two opportunities?

Haley Moss: Honestly, it really just depends on where you’re going. So sometimes you start just volunteering or, which is something that I’ve done is I signed up as a volunteer. Or I think about who has helped me in my journey. So there are certain organizations that have done things for me and my family, for instance. Or I’m like, I want to give back, I want to give time. Or sometimes they’ll even say “we have open board seats, please apply.” And I will force myself to be brave and do that. And I think that it’s tough to put yourself out there. The worst that can happen is no, or you just stay volunteering and you don’t have to take on leadership. Or what happens is a lot of folks that I know will volunteer and give so much time that someone that is in leadership goes, “why aren’t you making decisions? Why aren’t you on the board? You should be there, or I’d like to nominate you.” So it’s, it’s a little bit of networking and it’s also just being passionate. So I think if you are passionate about things, those opportunities actually do show up too. But I think there comes a time when you have to be a little bit more aggressive, if you know that’s what you want.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Haley Moss: Sometimes it’s as simple as finding out who like an executive director is and go, “I’m interested in serving on the board. I’ve enjoyed volunteering, but I’d like to do more.” Or sometimes it’s a little bit more aggressive than that. If you realize, it’s say disability organization with all parents on the board, “Hey, this is great that you’re doing all this work on behalf of disabled people, but there’s no disabled people on your board and that needs to change.” You can actually say that, and it’s not an insult. It’s constructive and necessary criticism when you’re just pointing out facts like that. And I’ve been on boards where I’ve gone, “hey, there are no disabled people here. This board is super white. This board is not diverse and does not represent the people it serves. This needs to change.” And if you get asked to be the work, then that’s up to me as both an advocate and ally to go, “here are three people who would be fantastic. You should consider adding at least one of them.”

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And I think having that solution, or just a suggestion really helps as well. You know, because people like, you know, oh, okay, well let’s do this.

Haley Moss: People always want to do things, and then they don’t know how to do them. So sometimes it’s like leading the horse to water before and say, here you go, go drink. Instead of going, you know, I’m thirsty. Like, here you go.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, absolutely. Yeah. Well, that’s great advice, really great way to remind people to get involved in their local communities, because you really can make pretty significant change there as well.

Haley Moss: You would be surprised. And you don’t know which individuals you might impact too. So maybe if you bring in a friend or a friend brings you in, you don’t know the impact you’ve had on each other.

Carolyn Kiel: Very true. So, you’ve written books and you’re a public speaker. Like what are your long-term goals for your writing and speaking career? Like things you haven’t done yet, or big goals that you still are working on accomplishing.

Haley Moss: I’m still trying to figure that one out. I got to give a TEDx Talk, which is super cool. So that was a big goal to get off my little list of things that would be awesome. But I think about this a lot now of what my goals are, because a lot of people, I know, we’re all turning, I’m turning 30 in like two years. And usually everyone thinks 30 is like this big, like milestone birthday thing. And for me, I think about what, what do I want when I’m 30? And like, I don’t know. I don’t have some perfect goal that I think I need to hit. Like most people, I know, think they’re going to be married. They’re gonna have like three kids or whatever it’s going to be. That’s not where I’m thinking. I’m thinking, you know, I just care that I’m happy. I care that I’m successful and I care that I’m well adjusted, whatever that means to me.

And that’s usually what I tell people is, everyone wants to be happy, successful, and well adjusted, but your mileage may vary on what that means to you. And I feel like a lot of the goals I have are the same ones at any other millennial has. I want to have a job that I love. I want to feel secure. I want to have a roof over my head. I want to be able to do things on my own time. I want to be happy. I want a life with hobbies and friends and family and love and all those good things that most people want. And it feels weird saying that a lot when I’m asked about my goals, because it’s the honest human answer. And it also, I think for the neurotypicals and non-disabled folk out there, it goes to show we’re really not as different as you think we are because we all want the same stuff out of life.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. And we all get to define what success looks like for us. So it doesn’t have to be like the single trajectory that, that is shared with us in society. It could be, as you said, just being fulfilled and happy and doing what you’re passionate about.

Haley Moss: Exactly. Like I know for some of my friends that means they’re getting married or they’re having kids right now. And I’m like, that’s great. But that doesn’t mean that’s where I have to be right now. And I think for young people, they really get this idea of the timeline. And that’s where things go kind of awry on goals. Like I admit, because I was on, I thought I was on the timeline at one point too. If you asked me 10 years ago where I’d be at this point in my life, I would have probably said, “I don’t know. Married? Kids? I don’t know.” And then I realized maybe that’s not what I want right now, or that’s not what I want, period. Like, it doesn’t really matter, but it’s the point that when we put ourselves to that timeline, I think it just sets us up to be disappointed if it doesn’t happen that way. And it’s okay if it doesn’t. Because honestly, I am happy. I am happier than a lot of my friends who did say, stick to a timeline and that’s fine.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah.

Haley Moss: I would be terrified if I was having a kid, like, I’d be terrified if I was having a kid right now.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah, timelines look different for everyone. And we all have different major milestones and we can change our minds and life, you know, unexpected things happen in life, like a pandemic that kind of like messes up plans, things like that.

Haley Moss: Exactly. And for me it was something that messed up my plans and also made my plans better and I had no clue that could have happened. And I’m also grateful that I got a ton of extra time with my family.

Carolyn Kiel: You never really know how things are going to work out, but you know, you kind of trust the process and, you know, as long as you’re working on things you’re excited about, you know, good things come from that.

Haley Moss: I would like to eventually feel responsible and home enough one day to have a dog. That would be nice. I think that would be a cool thing. And I know it’s kind of random, but I feel like I’m not home enough. And I feel like I’m also barely able to take care of myself, let alone another creature. So I would like to hit the level of, I feel that I can reasonably take care of a dog because dogs are great.

Carolyn Kiel: Yeah. Absolutely. So, yeah, Haley, thank you so much for sharing your story and talking about your books and sharing advice.

Where can we find your work? Should we go to a website, social media? Where can we find out more about you?

Haley Moss: You can visit me at HaleyMoss.com or you can say hello to me on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram. I love getting to connect with people and I am excited to stay in touch.

Carolyn Kiel: Awesome. So we’ll put those links in the show notes so people can find them there.

Again, Haley, thank you so much for being on the show. As we close out, is there anything else that you’d like our listeners to know or anything that they can help or support you with?

Haley Moss: I’m just glad that you chose to spend part of your day listening to us and hopefully getting to learn something. I just hope that you are someone who is happy and if you are an autistic person, I hope that you keep having a life that is filled with autistic joy, because so much of the world wants to focus on everything that is hard for us and our pain, that you deserve that. So you are loved, you are valid and please have that autistic joy in your life because it makes me happy and it makes you happy. And that’s all that really matters. Right?

Carolyn Kiel: Absolutely. Well, thanks again, Haley for being on the podcast.

Haley Moss: Thank you again for having me. This was a lot of fun.

[Giveaway and discount details]

Carolyn Kiel: Ok, here are the details for the giveaway and discount that I mentioned. Beyond 6 Seconds is running a giveaway for up to 3 lucky listeners in the United States to win a free copy of Haley’s latest book, “The Young Autistic Adult’s Independence Handbook.” To enter, check out my Instagram post on June 14, 2022. I’m @beyond6seconds on Instagram, and I’ll put a link in the show notes so you go right there. The giveaway ends at 11:59PM ET on June 30, 2022. Up to 3 winners will be selected at random in early July, 2022. This giveaway is valid for listeners at US addresses only.

Also, Beyond 6 Seconds has partnered with Jessica Kingsley Publishers to offer a discount on two of Haley’s books: “The Young Autistic Adult’s Independence Handbook” that we’ve been talking about today, and “A Freshman Survival Guide For College Students With Autism Spectrum Disorders.” This discount code is valid until July 15th, 2022, for listeners with shipping addresses in the US or the UK only. If you’re interested, here’s what you do. Go to the Jessica Kingsley Publishers website, which is jkp.com, add one or both of these books to your cart, and enter the discount code Moss20 at checkout to get 20% off those books. Again, the website is jkp.com and the discount code is Moss20 for 20% off those two books by Haley Moss. I’ll put the website link and the discount code in the show notes for you too. This discount code is valid until July 15th, 2022, so if you’re in the US or UK and you’re interested, go and place your order soon! Enjoy!

Thanks for listening to Beyond 6 Seconds. Please help me spread the word about this podcast. Share it with a friend, give it a shout out on your social media or write a review on Apple Podcasts or your favorite podcast player. You can find all of my episodes and sign up for my free newsletter at beyond6seconds.net. Until next time.